Hate or fear of "crossing the water" may be the only thing I have left of my mother's, my grandmother's. Surely, it's the only thing that I have that I know I have. Maybe I have something else and I don't know it. If the fear were truly mine, I could touch it more intimately, get into its crevices, or let it get into mine, and I would know it. This feeling hangs down low in me, a heavy lump of an unexplored thing, like a clod of brown-red mud giving off some old mother heat.

The old aunt died before we could pack for Nashville. I long for forest. I yearn for the trees and the horses of Jeems, the steam from their nostril sand the steam from their fresh dung. I miss the safe inland cities. Nashville, Atlanta. These cities with their front porches on the ocean, Washington, Savannah, Charleston, scare me, like a door left open on a dark night with robbers about.

But I am hungry for the city on the Thames. I think of the palaces, Hampton Court where Queen Elizabeth lived, I think of the Tower of London and all the things I read about in those Walter Scott novel sand those slow Jane Austen pages. The only one of those I ever loved at all was Mangeld Part. Fanny hated slavers. I think of all those ladies now because-why? Because-why? Because, having forgotten what I saw there, they are all I know of the world to which I am going.

Dusty pages. Mouse supper.

I laughed so hard at breakfast, my insides got tickled. I laughed so good, I was the giggle and I was drunk on it too. I laughed so hard this morning my stomach hurt from stretching and shaking. The deep belly laugh cures more than you know that ails you. I had forgotten that. It's been so long since I had one. The rumble and the jiggle of the thing does a woman more good than a poke. But the good strong belly laugh is harder to come by than a good stiff poke.

Debt Chauffeur, that's my name for him now, wants to marry me. He asked me down on bended knee, and I would have been honored-except he wants us to live in London, and he wants me to live white. I crowed at that. I laughed so hard, and not a tear came. He couldn't understand it. I don't often think on how white I look; it's always been a question of how colored I feel, and I feel plenty colored. He said that no one in London will know that I'm supposed to be colored. And I said I am colored, colored black, the way I talk, the way I cook, the way I do most everything, and he said but you don't have to be. She was "black" and she didn't seem it, and she was not that much lighter than you, and she was "black." At last that explained everything to him. I understood it near at once. It had never seemed before that he so little knew me. Always at least he knew the difference between her and me, and now he saw little difference, and the advantage was all to Other.

I tell him. Mammy is my mother. I think of her more as the days pass.

I can't pass away from her. He says she's the one asked me to do it. I don't believe him, and he hands me another letter. script was ornate but the words were crude. I didn't recognize the handwriting. Before I read the contents I guessed the fine script belonged to some Confederate widow, a general's wife or daughter, who owed a favor to Lady and repaid it to Mammy. But what I read Mammy would never have dictated to any friend of Lady's. I suspect she came to Atlanta, came to Atlanta and didn't visit me, came to Atlanta and got someone from the Freed Men's Bureau to do her writing. I can hear her saying, "Git it 'xact. I ain't here fo' no about." Syllable and sound, the words were Mammy's.

Dear Sur, You done already send one of mah chilrens back to me broke. Lak an itty bitty thang, a red robin, you done twist her soul lak da little neck and huah can't sang no mo'. She was mah Lamb, so I guess that how that goes.

Now you got mah chile. What was my vary own. Dat's a love child you got, Cinnamon. Skinny as stick, spicy and sweet. An eyes-wide-open-in-the-daylight child. She need a rang on her finger and some easy days, dat gal do. I had me the roof and the clothes, I watch huah Lady wear de jewels but Ah ain't ne'er cared nothing about dat. Ah done toted and tarried and twisted mah own few necks, but dis ain't about dat. Let mah child love you. And let Gawd love her too.

For what I done for you little Precious. Yo' chile dat died. Marry mah little gal. I am sincerely, Her Mammy Beneath the last two words Mammy had placed her mark, a cross in a circle.

cried enough to ride back to Africa on a slide of tears. "Mah little gal"-what I wouldn't give to hear her speak those words I see on the paper; what I would not give does not exist. I want to eat the paper.

I would give anything to hear her say "mah little gal." What am I writing? I would give everything to hear her say anything at all. I want Mama, I want my mother. I want Mammy. It's easy to want her, now that I know she wanted me. If I coulda wanted her when I didn't know she wanted me, she might be mine right now. She might be alive right now. Mammy never stood foot on London. Ah ain't goin' dere. I ain't goin' nowhere she ain't been. I'm staying here and looking for what's left of her.

gebt says all that's left of Mammy is me. He is polite enough to flinch as he says it. I ask him if he's imagining me fat and dark. He don't answer. He tells me about a dream Other used to have. A dream of hers. She was lost in a fog, running, looking for something, and she don't know what. Other never knew what she wanted, so she never had it even when she did. I ask him why he's still talking to me about her when she's buried in the ground. I say I know what I'm looking for. When I was a little girl I was looking for love. When they sold me off the place I was looking for safety. At Beauty's I was looking for propriety, and now, and now I have drunk from the pitcher of love, and the pitcher of safety, and the pitcher of propriety till I feel the water shaking in my ears. But thirst still burns. What I want now is what I always wanted and never knew-I want not to be exotic. I want to be the rule itself, not the exception that proves it. But I have no words to tell him that, and he has many feelings for me, but that is not one of them.

Later, I look at my reflection in the glass-and I try to see what he sees. I look for the colors. I see the blue veins in my breast. I see the dark honey shine of my skin, the plum color of my lips. I see the green of my eyes, and I see the full curve of my lips and the curl of my hair, and I _ know that it's not so very bad being a nigger-but you've got to be in the skin to know.

Am I still laughing? It is not in the pigment. of my skin that my Negressness lies. It is not the color of my skin. It is the color of my mind, and my mind is dark, dusky, like a beautiful night. And Other, my part-sister, had the dusky blood but not the mind, not the memory. There must be something you can do or not do. Maybe if the memories are not teased forth, they are lost; maybe if the dance is not danced, you forget the patterns. I cannot go to London and forget my color. I don't want to. Not anymore.

efhad never known him to be ignorant. But he is. He thinks like the others, the common tide. He thinks that the blackness is in the drop of blood, something of the body. I would have thought he knew enough women's bodies to know that that could not be true. And enough blacks and whites to know there is a difference. What did I suck in on Mammy's tit that made me black, and why did it not darken Other's berry? Was there some slight tinge, some darkening thing about Other?

Lady's fortitude; Other's willingness to take to the field? And how does one explain the sisters except that part of the blood memory must be provoked and inspired and repaired, time and again, to become the memory.

This tied-up-in-ribbons gift I want from him, he has no picture in his head of what that gift looks like unwrapped. No picture at all. The lift of a hat, the dip of his back-those gestures would remain as they have been, but the bitter curve of his lip holding back a laugh that salutes all that is strange and lacking in harmony in me, in him, in us, would vanish. That curve in his lips, that spark in his eye of-truth-yes truth, there is so much in me strange and discordant.

The notion of respecting me, as me, myself, would be, is, half foreign to his mind. No, no, not foreign; foreign is this coming week of travel, that idea is not foreign to him. Respect for me is foreign to me. Respect for me is an accomplishment of his, mine by gift, not mine by right. Absence and exoticism are such different keys of longing. He adores me, he has worshipped me, I believe he loves me, but never could the tone of his feeling be formed so that this cautious emotion, this sturdy food, "respect between equals," be what you called the way his heart turned toward mine.

It was always some warmer feeling, not the cold distance of temperance.

I want his respect. I have fragments of it and fractions. He admires my mind. I have read more books than any woman he knows well. The way I break rhythms, the way I make rhythms, he yearns for the music of my way of telling, of being, of seeing. But now our love songs are played in two keys: grief and remorse. I prefer grief to remorse. Without mutuality, without empathy to join and precede sympathy, I am but a doll come to life. A pretty nigger doll dressed up in finery, hair pressed for play. I will be the solace of sorrow but not the solace of shame. I have been dropped too deeply into the shame bucket to borrow any that belongs to somebody else. I wrap my shame in his respectability, I let his arms wrap 'round my shoulders, his weight press me into a sense of place. His self plunging into my heart awakens me, and, with it, a weak humiliation I've known so long, an aching bruise it pleasures to touch.

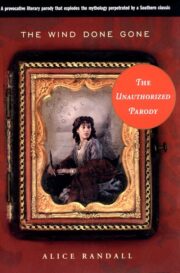

"The wind done gone" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wind done gone". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wind done gone" друзьям в соцсетях.