If Other bore her discomfort with little grace, Mammy bore it with less. Mammy gained fifty pounds one year, forty the next, twenty the year after that, and the slight, barely hundred-pound body in which she had walked into the house and slipped into Planter's bed vanished beneath another hundred pounds of protective flesh. I believe Mammy felt Other pulling away from her, and she determined to pull away from Planter before he could pull away. Overnight, Mammy became a stout old woman of fifty.

Lady was ripe then, thirty, and maybe she was just a little hungry for what she hadn't known when Planter, stone drunk, ploughed into her stone-dry and laudanum drugged body.

She had felt no pleasure, had given no pleasure, felt no pain, gave no pain, as he flopped about, planting his seed in her soil. These were the days when she began to wonder if there might could be something more to these engagements. She was beginning to forget her girlhood.

At the same time Other was becoming uncomfortable with Mammy, she began to fall deeply in love with her mother, my Lady. I wanted to dash her brains out with a big rock. Other and Lady and Me. As they discovered each other, I discovered the higher temperatures of jealousy. The fever comes in different degrees. Other's love for Lady's tidy, tiny, sweet-smelling self, her slight but supple arms, the white, heaven-pillow bosom that lay corseted beneath Lady's modest gowns, brought sweat to my brow. It was a comfort to know, it remains a comfort to know, that Other died without ever once seeing her mother's breasts, breasts on which I sucked.

And Planter was beginning to see me anew. There was nothing strange between him and me. I was his daughter, and that meant more to him than it did to most men of his time and station when the daughter was brown. But the way he looked at me, Mammy didn't know if she was nervous or jealous. And not for the first time Lady felt the exact same thing.

Back then, I was hating Other so hard for breaking the ribbons binding Lady to me that I noticed all of this, but I didn't weave it into the fabric of my understanding of my life. Yet circumstance has left me rich in time to think about those days. Not working is a severe affliction. If I had been turned out to field work, perhaps I would never have whipped up so hard on my own mind. But everything changed when Other fell out of love with Mammy and in love with Lady.

Everything changed when Lady fell out of love with me. Everything changed when Planter noticed that I was some kind of cross between his wife and his woman. Everything changed, and they sent me away.

I could see in Other's face the first moment it came to her the possibility that Mammy did for her not because she wanted to, but because she had to. Maybe Mammy loved her and maybe Mammy didn't.

Slavery made it impossible for Other to know. "She who ain't free not to love, ain't free to love." Some folks are easy with that and some folks are not. Mainly the folks who think they wouldn't be loved are easy with it.

What Lady did for me, she did freely. And what she did for Other was done that way too. So I for sure got something. I can't decide if I'm grateful that R. will finally never have to choose between us, between me and Other. Sometimes when I feel neither lucky nor worthy, I'm grateful to get the win any way I get it. Sometimes I can taste beating her out and I am sad to be starved of it.

Sometimes it feels like the game is over and I'm putting up the checkers, and instead of me winning, she just lost, or more like she never showed up. And that's something else altogether from the way I want to feel, triumphant! Winnerly. However it happened, I'm just glad not to lose.

Other is dead, and I'm sorry for it.

I want to go to Mr. Frederick Douglass's house and I wouldn't be sorry to go without R. if I could go in propriety. I like moving among these Capital City Negroes. I met a young seamstress who mainly sews for white families, but she's going to do a bit of work for me. Rosie Woodruff is her name. There is something in this quick, trim African lady, something so city-like but clean that I had to drop my eyes to keep her from seeing that it was me who is admiring her. She wore a pitifully slim gold ring on her finger, and a skinnier brown-skin man was waiting for her at home, a plumber who came very lately from someplace deep South and had quick picked up a trade. Compared to this seamstress I have so much-or is it so little? Home feels far away.

Every mile of the distance feels safe and getting safer. And every mile and hour it feels like something more of me is missing.

Say I walked around the monument to President Washington. It's a half-finished thing, an odd white thumb coming up out of dirt and a few blades of grass, a stump of a thing, blasting through the dome of a cracked-in-two shell of sky.

The light in this city is so different from the light at the farm in Georgia, from the light in Charleston. The sky here is colored the blue of a robin's egg if the shell had been heated up with yolk-colored, straight-from-heaven sun rays Always about me now is the sense of having died and gone to heaven.

Or died and gone to hell. Died for sure. There is a thickness to the Washington air. It's heavy with water and mosquitoes. I wear this air like a coat that keeps me from the cold I know is coming. And there's a thickness to the river. You can't see very deep into it for all that it carries, and it's wide. The Potomac seems to roll in here from someplace and curve slowly through the city like it's a good place to stay.

When I sailed to Europe I did not remember my fear of water until I was upon it for some days. Or was it Mammy's fear I remembered? Or Mammy's Mammy's fear? Where does fear go to become fascination? Is it where rivers go to become sea? More than anything I saw of Venice (gondolas, masks), of London (pints, a palace), of Paris (sewer rats, stained glass) after so much land, I saw all the rivers. The Potomac brings back to me a remembrance of rivers. A remembrance of rivers and river cities.

Walking along the streets I hear different languages. And the people dress differently not just because they are rich or poor but because the people of Atlanta dress differently from the people of Boston, who dress differently from the Philadelphians and there is a good bit of everybody roving 'round here.

In a way Washington, the Capital City, feels like an island. It belongs to nothing. I wonder what will be here in a hundred years? I wonder if anything will be here at all. The city is like a big pregnant woman Lying on her side while everybody fans her and wonders when she's going to give birth. Or will the baby blast the life out of her, trying to press its way into life? We hear stories about the French L'Enfant and the black man, Banneker, who was his assistant, and how they were tossed out of their own vision, out of this town of their creation, for dreaming too wildly. Are there tame dreams ? I wonder if this city with its strange circles, somehow designed to make one cannon do the work of six, but not generally sensible, I wonder if this city won't always be a kind of ha into struggling to wake to the everyday needs of a struggling rural people, struggling to fall back into L'Enfant's grand dream of a city of Senators and Ambassadors? Did he not understand our Congressmen were not so long ago farmers and slaves? He didn't know that. I don't believe the European ever fully understands the American. But this city is built for tomorrow, and tomorrow I go the Douglasses' for tea.

I went to the Douglasses' for tea. Their home is more than a bit out of the way. Perched in the southeast quadrant of the city, high above a riverbank, Cedar Hill rewards the adventurous sojourner with a superb view across the Anacostia to the Federal city.

It's a new kind of home for me. There was a comfortable expanse but no formality-in the architecture. The formality was in the language, and now I borrow it for mine.

Was this the first party in my life I had attended alone, unescorted?

Has any other woman in the world arrived at a formal party on her own? I surprised myself by going; I surprised a few of the other guests, I expect. And I was glad I did, from the moment a gap-too the girl with an intelligent smile, gold-rimmed glasses, and long puffy-kinky hair opened the door and waved me in to join the crowd.

The party revolved around an immense cut-glass punch bowl filled to the brim with what tasted to be a mixture of fruit juice and tea. This bowl sat in the middle of a draped round table in a square entry hall.

There were no big crystal bowls of flowers and no waiters, just shining faces and everyone helping themselves.

In the corner of the drawing room three young women from Fisk University in Nashville gave an impromptu rendition of "Soon I Will Be Done with the Troubles of the World," and this afternoon I felt I wouldn't have to leave this earth for it to be true.

We, Frederick Douglass and I, barely exchanged three sentences, but he looked at me as they sang, and I could see that he liked what he saw.

As I was making my way through the crowd (so many sky-blue, so many cardinal colored gowns-the effect-due to the new dyes-was quite unintentionally patriotic) after the song, twice the great man nodded as he smiled in my direction.

I never got too close to Douglass again, but I enjoyed a lively conversation with his son. I enjoyed this party. It was a kind of Negro open house, the kind of event to which I am not frequently invited. Mulatto mistresses of Confederate aristocrats have little standing in Negro society. And the Congressman was there.

God was showing off the day He created the Congressman. He is that good-looking. Or maybe God was just taking a stand. Who will deny the humanity of such a body, such a mind?

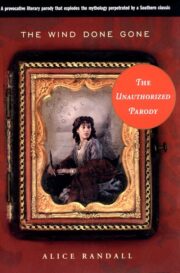

"The wind done gone" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wind done gone". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wind done gone" друзьям в соцсетях.