“Those big red-haired boys?”

“Them." He nodded, but there was an unspoken question hiding in his smile.

"Jeems was their tenth birthday present. He was ten too.

"The Twins are dead now.”

“Yeah, they are.”

“Gettysburg.”

“Gettsyburg." Already R. had lost interest. He wasn't interested in slaves. I tried another smile, but my mouth sort of stuck to my teeth, and all I made was something that looked like snaggles peeking through half a moon. My face was changing. I wondered if he could see it yet. I smiled the half-broken smile that conceals. I achieved a fraction more. The edges of my lips were heavy, and I could feel the inside of my lips sticking to my teeth.

Always, when I'm awkward or clumsy, I'm grateful for beauty which causes men not to notice my other imperfections.

I wanted to ask R. if he was grateful for my beauty, but I did not.

Questions like that can only be written here. They can't breathe. Is he ever grateful for anything I do?

I told him I was tired, and he told me to be down in time for the evening meal. I told him dust was with me still. Dust of death and dust of road. I needed sleep, day sleep now, and water. I blinked, and then I wanted to cry with no cause.

He said, "Be down in time for supper. A Congressman IS coming to call.

At noon the young maid brought dinner up to my room: cold fried chicken and a glass of wine. She is an olive-skinned, straight-haired girl, a slim-as-a-beanpole beauty, heavy on her feet, but there is a lot of Indian in her nigger. She closed the door behind her when she entered.

Just then she appeared a breathless, hipless, and un sexed creature.

The drumming of her feet as she crossed my room, placing the tray or unpacking my bag or storing clothes away in the chifforobe, lulled me to sleep. I fell asleep and dreamed of Jeems.

It was a very bad dream. I dug up the grave of the last of the dead baby boys. The one born the year I went away. I dug into his grave, opened the coffin, and Jeems popped out, live, like a jack-in-the-box.

He had a hundred white teeth. There were too many teeth, but they were so pretty, like pearls bright shining, and I was glad he had so many yet repulsed at the same time. I wanted him to stop grinning so he would still have the teeth but I wouldn't see them.

But he wouldn't stop grinning, and I couldn't get the lid of the coffin back on. I woke up with sweat and tears running down my face. I just had time to dress.

I'll be late down to supper now. But R. say the Congressman will be later. I hope Mrs. Dred larded the turkey enough so the meat won't be dry with long cooking. Of all our peculiar customs, I find it strange that we denizens of the Southland don't have a taste for cool food -even in August. I told her to wrap the turkey in bacon before cooking, but she knows I don't like to serve the turkey with the bacon on it, so I suspect the bacon is someone's dinner and not on the turkey at all, and I can't be angry. Everybody needs to eat.

R. came into the room and led me to the bed. He lay me down upon it.

And undressed me as if I was a child. He sat down beside me. He kissed my forehead and my lips. Ran his hand across my belly. His hand just hovered over the curly dark separating my thighs. When he looked at me this way, I knew he wouldn't love me. Wouldn't touch me. Wouldn't take me.

I still stir his mind, but I can no longer for sure stir his body. He is still beautiful. Men seem to start glowing with years. I wonder if they shine with the invisible candles that light up good leather when it ages. He wears his wealth on his face. Life has carved a leanness into the bones of my man that the years of plenty and the years of excess, drink and food, do not blight-completely.

Light in August. I used to be scared I would have a baby. Now I am scared I will not. My waist is narrow as a virgin's, and my stomach is baby less flat, my breast baby less high. I like to think I wear my years lightly. Virgins go dry and age quickly into brittle spinsters.

Women who are touched by many different men become shopworn angels. You can see the smudges of bourbon breath mottling their eyes. Mothers grow flaccid, rich in baby love, each baby taking some of the mother's beauty as if the baby knows it needs to protect its baby self by making Mama less kiss-daddy pretty. Each baby knows the baby to come takes something away from the baby in arms, so little Jenny and little Carrie cry in the night just when Daddy's rising. They gray Mama's hair and suck the fullness out of her breast. Filling her heart with such love, she don't need to look in the mirror to see who she is. I learned all that at Beauty's. What the babies take away, the girls paint back on.

Me, I'm looking in the mirror, still. The mirror on the wall and the mirror in his eyes. I see Beauty grow blowsy; I see Other grow wider with the laying of three men and the birthing of three babies. Me-I've only had one man and no babies, and so my skin is not etched like marble with the pale wiggling seams where life stretched forth to cover life-but I am greedy for weight, the weight of life growing within me, the relief the old cow knows when she delivers in July and is light in August.

"Do you ever think about marrying me ? " he asks.

"No.”

“I'm thinking about marrying you." I sit up on the bed. I don't look at him. It's time to get my dress on. I smell dinner ready in the kitchen. I wonder if Cook did lard the turkey. R. kisses me again on the forehead. For the first time in a long time, I wonder how much I remind him of Other and how much in his eyes I resemble their child. He outlines the curve of my eyebrow, and I know he is thinking of them.

I had to get this down. But now I have to dress. I will put on the red gown and the large gold hoops in my ears. I had intended to choose a more subdued dress, but I feel, after R.’s declaration, it will be amusing to play with his notion of who I am and watch him squirm. He's playing with me. I will not play in the shadow of Other.

he Congressman was colored. And I could not have been more charmed. I wish I could have changed gowns. Unfortunately, all he did was find fault with me, too many faults for a different dress to have helped.

There were three of us at table. Instead of placing our guest between us, R. sat me in the middle as a kind of no man's land. Each man sat at a head of the table.

I wished from the moment I walked in that I hadn't worn my hoops. Under the Congressman's gaze the hoops felt niggerish and the deepness of the cut of the bosom of my gown seemed sluttish.

But R. seemed pleased. He expected the Congressman to admire me, so all he saw was admiration.

The dinner began slowly. There was some kind of soup, a hot soup served in handled cold creamed soup bowls that made me cringe, and the turkey was dry. We had chess pie for dessert, a recipe that come over from Tennessee, like pecan pie without the pecans. It was an after-the-war food, elegant in its unadorned poverty. The Congressman smiled at his first crispy-sweet bite.

R. caught this, and laughed. "You don't believe me. Cindy is not your ordinary lady-she's been on the Grand Tour.”

“My goodness." For the first time the Congressman was impressed.

"You and Mrs. Hemmings?”

“Mrs. Hemmings?”

“Mrs. Hemmings who Jefferson took to Paris." R. and the Congressman begin to share a laugh at my expense. To veer back to politeness the Congressman directed another question to me.

"What ship did you cross over on?”

“The Baltic.”

“How funny, how very funny." Now the Congressman was laughing anew, and I was laughing too. We knew about the Baltic. Only R. was still laughing at the old, cold joke, embedded like an insect in amber, that the slave Hemmings' stay in Paris had been a Grand Tour. And while we free Negroes were laughing at the strangeness of transformations, I was wondering what Lady would think of my table.

Later, when I poured them coffee and they were enjoying their cigars, before their business began in earnest and I would retire, the Congressman asked R. if he was following the career of "my friend Francis L. Cardozo. You might be useful collaborators."

"The state treasurer?" responded R. "Exactly.”

“I know the name.”

“He was educated in Glasgow and in London. He was a minister in New Haven. Since the war he's been the principal of a school for blacks in Charleston. Next time you're in Charleston, you should see him." R. shrugged. His cigar had gone out. He lit it again.

"It would be interesting to meet with him in Washington. Or bring him to see us in Atlanta." R. changed the subject. If he was interested in the South's new colored leaders, he wasn't interested in them in his beloved old seaside town. He might eat with them in Atlanta or Washington, but he would never eat with them in Charleston.

I wonder what this means for me?

And I wondered if the Congressman had raised Cardozo's name at just that time, the moment I was pouring, to raise just that question in my mind.

We crossed the Atlantic Ocean on a ship called the Baltic. The crossing took seventeen days. My hate of seawater did not emerge until I was upon it for at least three or four. It popped up the way one of the sailors said that icebergs do.

Out of the fish-rich darkness emerges this white, killing thing.

Pointing straight up to the sky. A ship is like a cotton farm.

Everyone has his place. There are the officers and the sailors. From the officers' uniforms dangle brass buttons that sparkle like stars against the blue, the way soldiers' buttons do.

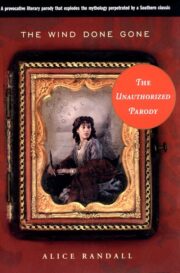

"The wind done gone" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The wind done gone". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The wind done gone" друзьям в соцсетях.