Louise cleaned him up as best she could then ordered Brown and Lorne to carry him to one of the empty servants’ rooms in the attic, to sleep off the drink. She followed along, thinking it was probably a good thing he was drunk. The alcohol numbed the pain, for the time being.

When the other two men left the room, Louise lingered behind. She tenderly pulled the sheet up over Stephen Byrne, smoothed her fingertips through the black wing of hair fallen over his forehead. “Sorry,” she whispered. “I’m so very sorry.” Then she sat down to watch over him while he slept.

Thirty-eight

Byrne woke with a start. He flung a defensive arm wide and bolted upright—disoriented, lungs rasping. No one came at him with knife or cudgel, but needles of pain jabbed his knee.

On a bed. He was on a bed, alone in a room . . . somewhere. He fell back down into the linens with a groan, lay still, waited for the wretched knee and dregs of the nightmare to subside. But now his ribs ached from the sudden movement. And his head throbbed like a military drum. He squinted down at his body. Someone had undressed him, but for breeches, and taped his knee and ribs. His face felt stiff with bruising. Every muscle in his body called out to him.

He had imagined himself back in the alley, set upon by a dozen pipe-wielding thugs. Then he recalled that Darvey was dead. And, unless he was still mixing dreams with reality, there had been a bizarre interval of camaraderie with the Scot that must have resulted in his current hungover state.

Slowly events reeled back through his mind. He recalled Brown retrieving his Colt from the grate, hauling him to his feet.

Byrne looked around the dim, silent room, trying to place himself. The space was not much larger than a closet, the bed narrow, single window darkened with a heavy muslin curtain. The walls were plastered and clean but bare, except for a plain wooden crucifix over the door, as if left by a previous occupant or put there as a suggestion of piety to a future resident. A monk’s cell? More likely servant’s quarters.

But of course. Brown, or whoever had helped him out of his clothes, and into bandages and bed, wouldn’t have snugged him up in Buckingham’s family wing. They’d hidden him away, hoping Victoria wouldn’t discover he’d been fighting again. And yet he wasn’t concerned. It was fighting Brown that had gotten him into trouble before. Not fighting alongside the Scot, for the protection of the queen’s daughter and grandson. Although, he was sure, Victoria would never publicly recognize Edward Locock.

Slowly, muscle by tender muscle, Byrne eased himself into a semitolerable sitting position and shifted his legs off the side of the bed. He let his body adjust to this new angle, then looked down and saw a sodden bundle of toweling. Ice, he thought. Someone had taken care to apply cold compresses to his injured knee while he slept. That was probably why the swelling was no worse than it was now.

He tried to stand and felt elated when he was able to put weight on the leg. A minor miracle.

Someone had cleaned and hung on a peg his clothing—minus pants, which must have been ruined. They’d been replaced by another pair with a drawstring at the waist that looked like something a gardener might wear. He relieved himself in the chamber pot then dressed, cuffing the too-long trousers. It took him a good twenty minutes to make himself moderately presentable.

He heard someone on the stairs outside his door and tensed. A moment later a soft knock sounded at the door.

He hobbled over and opened it.

Louise stood there, her face aglow, her lovely golden brown hair brushed loose and shining down her back. She looked even younger than her years. She smiled. “You’re standing.”

“I am. Damn proud of that.”

She held up a tray arranged with what appeared to be a fortune in silver-domed dishes. “I thought you might be hungry.”

“Starving, but you didn’t need—”

“I did need to. What little I would have paid you to watch out for the Lococks wasn’t sufficient for risking your life as you did.”

“I doubt it was that serious.”

Louise gave him an “oh, please” look and brushed past him and into the room. She looked around, seemed startled to see no table to set it upon. It occurred to Byrne how heavy the blessed thing must be and he kicked himself for not having taken the tray from her right away. He pulled the one straight-back chair over near the bed then took the tray from her and set it on the chair’s seat—an improvised table.

She said, “I heard enough of Mr. Brown’s recital of the fight to come to the conclusion you very nearly died in the line of duty, Mr. Byrne.” She met his eyes. “Stephen,” she amended.

“I am, I admit, in debt to the Scot. But it’s possible I’d have survived.”

“Well, that’s an optimistic view.” Her laugh, to his ears, held a near hysterical edge. Her eyes glittered with unshed tears as she turned away from opening the curtains to let in the sunlight.

Byrne sat on the bed and smiled when he noticed two cups on the tray. He patted the mattress. Louise sat demurely on its very edge, a good two feet away from him.

He poured tea, lifted the lid of one of the servers, and found thick rashers of bacon and fat sausages.

“There are hard-cooked eggs under the other cover,” she said then lifted a cloth napkin to reveal slabs of toasted bread under pools of butter.

“A meal fit for a king,” he murmured over his split lip. It would hurt to eat, but he was famished.

“I seriously am most grateful,” she said. “If that dreadful man had got into their house, had put his hands on Amanda ever again . . .” She shuddered visibly and blinked at him. “You cannot know what she went through before she and I met.”

“I think I have an idea,” he said.

“And the child.”

“Your son.”

“Yes, mine.” She blew out a little breath. Of relief, or merely acknowledging the truth? “My . . . son. Though we shall never speak of him as such in the presence of others.”

“Understood. But he will learn someday.”

“Will he?” She frowned. “Amanda thinks we should tell him when he’s older. I believe such knowledge would only cause him pain, and much trouble. Better that he believes he’s the son of a fine London physician than the bastard of a reckless princess.”

He smiled at her. She was so beautiful, so young. Yet she’d been through so much. And all because she refused to confine herself to the role her family dictated for her.

He had heard the way ladies and gentlemen of the court, and the queen’s subjects, spoke of Louise. The “wild princess.” The young royal who fought her parents’ authority at every turn. She demanded the right to study art with commoners and—even more shocking—to sit in the same classes with men and learn what they learned. The princess who caroused in pubs and smoking dens with her Bohemian friends. Until something happened to cause her to settle down.

Gossip said Louise finally grew into adulthood and accepted her royal role. How could she not, with Victoria’s thumb on her? And now that she was married, they expected her husband would take over the reins and control her. He’d give her children to further anchor her to a respectable life. Like a ship caught up in a gale, if you took down her sails and threw out enough anchors, she’d eventually weather the storm. That’s what they thought.

Little do they know.

Byrne watched her sip her tea, select one of the smaller strips of bacon, and nibble it. She gave the appearance of being utterly at peace. But beneath the outward calm he sensed extraordinary effort. Against what forces was Louise fighting now?

He ate without speaking, forcing himself not to gulp down the food all at once. It tasted so good. He felt so good!

That was the best part of a fight. After it was over, you felt more alive than ever, because you had feared, and nearly known, the alternative. Because you’d straddled the line between life and death.

“The Fenians,” she said, out of the blue.

“Yes?” He lifted his eyes to fix on hers and felt as if he was tumbling into them.

“You are still on their trail? Still concerned that they will strike again?”

“I am, on both counts.”

She finished her bacon in one bite then stared out the window for a long while, as if in contemplation of the future. “Why are you doing this?”

Wasn’t it obvious? “It’s my job.”

“No, I mean, this isn’t your fight, Stephen. You are an American, not a subject of the Queen of England. You are putting your life on the line daily for us. These are dangerous men, desperate men. They will stop at nothing.” Her voice quavered with emotion. “Whether or not their cause is valid, what they do is not right. They kill innocent women and children who happen to be in the path of their bombs. They won’t hesitate to murder a man who has vowed to stop them.”

“True.” He studied her profile. It was so finely shaped, she might have been etched in glass or carved from pearly onyx. It seemed right that the sculptress should herself be perfect.

“I am going to ask the queen to dismiss you,” she said.

“What?” He stared at her. Of all the things she might have said to him, nothing could have shocked him more.

“I will tell her you fought again with Brown. Convince her that you are a dangerous influence on her Scot. She will have no choice but to send you home.”

He threw back his head and laughed.

She seemed startled by his reaction and pulled away to stare at him in confusion.

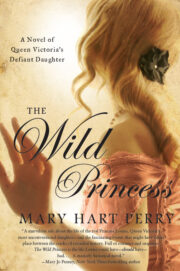

"The Wild Princess: A Novel of Queen Victoria’s Defiant Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Wild Princess: A Novel of Queen Victoria’s Defiant Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Wild Princess: A Novel of Queen Victoria’s Defiant Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.