Unfortunately—Louise had to admit—her mother’s fears proved warranted. Although that one year in Kensington had been the most exciting, enlightening, and challenging of her young life, disaster ensued. Painful images flashed across her mind, even now, in the rumbling coach, so many years later. She brought a gloved fist to her mouth and pressed hard, holding back a sob of grief . . . and guilt.

With effort Louise pushed those memories out of her mind and fixed on the budding trees and early blossoming, white-petaled snowdrops speckling the grass alongside the road. And the pain slowly faded. In a few days they’d settle in at dear Balmoral, the castle built on an ancient site by her father. It sat close to where her husband had been born into the powerful Campbell clan, and where his family still lived. As always, the castle would offer shelter from the politics and intrigue of London.

Occasionally she caught a glimpse of her mother’s agent, Stephen Byrne, riding up and down the line of carriages, his black-brown duster flapping in the wind, that strange American plainsman’s hat with the high crown and wide brim tugged low over his brow, his piercing gaze flicking toward buildings, trees, people they passed. Watching for God-only-knew-what threat.

She had to give the man credit. He, and Brown, had acted swiftly and efficiently to get them on their way north. It was no small task, herding their entourage into the waiting carriages. She’d expected outraged arguments from courtiers. But something unpredictable and dangerous shadowed Byrne’s dark eyes, discouraging argument from even the highest ranking in her mother’s court.

She looked along the seat and over her sister’s sleeping head at Lorne. His gaze was fixed on a distant point outside the far window. His blond hair feathered in the chill spring breeze. They hadn’t said more than two words to each other this day. Or the one before it. In the presence of her mother, he’d kissed her on the cheek and wished her a cheerful good morning at family breakfast. But since then he’d touched her no more than was necessary to put on a show of affection and, later, to hand her up into the carriage.

She felt more alone than ever, shut inside this rattling ebony box with her nonhusband and her incomprehensible mother. How could she look forward to a life of celibacy, in the company of a man who could only love other men? What was she to do? If this had been a conscious plan on her mother’s part, had it been intended as punishment for her daughter’s past failings?

Louise’s head began to pound in rhythm with the horses’ hoofbeats. Her throat felt raw and tightened with the effort to fight back tears. She wouldn’t succumb to self-pity. Certainly not here in front of everyone.

The queen’s carriage set a rapid pace between towns, at Brown’s direction. Eventually they slowed down as they approached the industrial town of Leicester, more densely populated than others before it along the route. Smokestacks spewed gritty steam from the factories along the canal and the River Soar, but the air remained far less foul than the choking effluvium that hovered over London.

And then they stopped.

Victoria roused herself, opening her eyes. “What is it? Why are we not moving?”

Louise leaned a little out the window to see beyond the horses that drew the carriage. “It appears to be market day. The streets are clogged with farm wagons and stalls.” Every few feet along the street a different display of winter crops lay in a cart, arranged on planks or on the ground: piles of new potatoes, purple turnips, plump rutabagas, green and red leafy chard, brilliant orange and emerald winter squashes. The air smelled of the earth, rich manure, and, more pleasantly, of pasties baking.

Farther ahead of the coach and the mounted guard, a flatbed lorry loaded with sacks of flour straddled the road, unmoving, apparently blocked by something that kept it from negotiating the tight turn.

Lorne roused himself to lean out the opposite window.

“Bother,” her mother fumed. “Brown promised we wouldn’t be caught on the road at night. This will put us off schedule for our first overnight with the baron and baroness.”

“It’s all right,” Lorne said, his voice soothing as he settled back into his seat and drew out a cigar. After a pointed glare from Victoria, he tucked his smoke away without lighting up. “They’re working to move the thing out of the way. Once we’re through the town, we’ll have open country again. Nothing to worry about, ladies.”

But with the caravan at a halt, townspeople began to crush forward in a human wave, peering into the carriages, eager for a glimpse of the royal family. As word spread, more people burst from doorways, pressing still closer. Two little girls ran up to the queen’s carriage and tossed a nosegay through the window.

“Oh!” Bea cried, waking up when the posies landed in her lap. She smiled sleepily. “Pretty.”

Another woman lofted a hand-worked doily through the window. “We love you. God save the queen!” she cried.

Victoria looked down at the little scrap of ecru tatting on the floor of her carriage. “I suppose they mean well,” she murmured. “But these people make me so nervous.”

“It’s all right, Mama,” Louise comforted her. Her mother sometimes behaved as if commoners belonged to another species. One that frightened her but she felt compelled, on occasion, to appear before.

Brown climbed down from the top of the carriage to curse the lorry driver and order him out of their way. Stephen Byrne leaned down from his horse to instruct their two footmen and closest guardsmen to ease the queen’s admirers back a few paces.

Preoccupied with her own thoughts, Louise took in only a hazy view of all that was going on outside their carriage. There seemed little reason to be concerned as, sooner or later, they’d move on.

She didn’t, at first, take notice of the young man who broke through the line of horse guards and rushed toward their carriage with something in his hand. No doubt, her subconscious whispered, another token of respect.

But when his arm thrust through the window nearest her mother, Louise could see that neither flowers nor anything else equally harmless rested in his hand. The object was solid, metallic, dark in color—with a short, mean muzzle.

A pistol!

Louise felt a physical jolt, first of disbelief then shock as she stared at the narrow, beardless face. Now only inches away from hers.

The man’s eyes, wild with intent, searched the passengers’ faces for only a moment before fixing on the eldest female in the carriage in black mourning garb. Momentarily frozen in time, Louise watched in horror as the young man’s arm swung to the left, pistol with it, to stop and point at her mother’s face.

Instinct took over, setting Louise’s body in motion. She thrust her sister aside and into Lorne’s chest. It wasn’t, then, so much a voluntary act as imagining herself transported to the space between the evil weapon and Victoria. Leaning across the gap between the two bench seats, Louise swung her arm as hard as she could at the rough wool coat sleeve stretched out in front of her, hoping to knock the gun from his grip.

Unfortunately, before Louise could connect with either arm or weapon, or even before she could push her mother out of harm’s way, she felt herself pitching forward. A brilliant, bluish white flash issued from the gun’s muzzle. She smelled a metallic tang in the air. Heard the explosion. And at the same awful moment realized she’d put her chest directly between the gun and Victoria. A blaze of heat from the ignition of powder struck the base of her throat and flew up the left side of her face.

It was as if time sped up a thousandfold—everything happening at once: men shouted from outside the carriage. Screams echoed from inside—her sister’s, her mother’s. Lorne yelled, “Assassin! Assassin!” Her two brothers threw themselves out the far door and into the street.

“She’s shot! My daughter,” Victoria screamed. “Lord, help us.”

Louise realized she was actually grasping the man’s gun, though it remained still in his grip. The hot metal seared through her glove into her tender palm. The astringent smell of burnt powder stung her nostrils. Her chest cramped with fear. Knowing she must be hit, but not daring to look down at her body, she assumed shock was probably blocking the pain but that it would soon be overcome by the severity of her wound.

Outside, someone snatched the man. She lost her grip on his sleeve and tumbled down onto the carriage floor—dazed, confused, unable to breathe.

Behind her, she heard Brown ordering the others out of the carriage. Sobbing and wailing, the queen and Beatrice fled through the far door, their skirts dragging across Louise’s face as she gasped for air, instinctively searching with her gloved fingers for the flowing wound. She must compress her hands over it, slow the bleeding until help arrived.

Why, she wondered, was time moving so damn slowly now when it had been like lightning moments before?

Then the door at her feet flew open. Byrne crawled in on hands and knees between the two seats and, quite literally, on top of her. He stayed low, holding his weight off of her but hovering inches above—as if to shield her while he examined her, head to foot.

His bright, black eyes fixed on her bodice. She followed them, taking a quick breath for courage. Her cashmere cloak had come open, and the lace ruffles over the bodice of her saffron traveling gown were blackened with powder burns. Byrne didn’t hesitate. His fingers tore into the delicate scorched fabric, opening layers all at once, straight through to her skin.

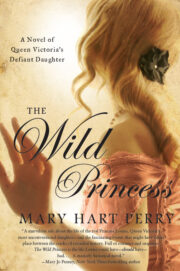

"The Wild Princess: A Novel of Queen Victoria’s Defiant Daughter" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Wild Princess: A Novel of Queen Victoria’s Defiant Daughter". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Wild Princess: A Novel of Queen Victoria’s Defiant Daughter" друзьям в соцсетях.