Christian turned to wave; his groom, whose livery, she noticed, should have been replaced some months ago, helped him on to his horse, bowed, and Christian waving to his wife at the window rode off.

She smiled, thinking of her tall blue-eyed husband, Prince Christian of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg – a very magnificent-sounding title for a penniless Prince. But they were fortunate because of the kindness of the King, which was good of him really for they had no claim on him. Christian was merely the fourth son of Duke Frederick of Schleswig-Holstein; and even the eldest son had inherited a bankrupt kingdom because the Napoleonic Wars had ruined them; but since there was a family connection, King Christian VIII had befriended his young namesake, had given him a commission in the Royal Guard and the Yellow Palace for his home.

They were lucky. The palace was not unlike a French château of the smaller type. One stepped into it straight from the street, entering by big gates which opened on to a courtyard. It was an exciting house, even though some of the rooms were small; there were odd winding staircases and passages and nooks and crannies in unexpected places. It was, in any case, a home, and they were grateful for it.

King Christian lived near by in the Royal Palace and Prince Christian and Louise were often invited to pay an informal visit; close by in an imposing mansion lived Louise’s parents – the Landgrave and Landgravine of Hesse-Cassel. The Landgravine had been Princess Charlotte, and was King Christian’s sister.

It was all rather cosy and informal for Charlotte was good to the family at the Yellow Palace and was constantly sending gifts and between the King and the Landgravine they just managed on Christian’s pay which was only ten pounds a month. Not very much to sustain life in a palace – even one such as the Yellow Palace – and maintain some semblance of royalty. But Prince Christian was happy; he was proud of his position in the Army; he had a wife whom he admired as well as loved, a son and another child on the way; he asked only to be able to keep them in comparative comfort.

Louise turned from the window. There were the servants to receive their orders – not many of them, only those whom her mother said she must have. Louise could manage very well. What a difference there had been in the Yellow Palace since she had taken over! Now all the cobwebs were swept away and the furniture shining; meals were served hot and promptly. She was a wonderful housewife.

The Landgravine tut-tutted and reminded her that she was the niece of the King, to which Louise replied gravely that she had reason to remember that with gratitude for to the King they owed their home and Christian’s post in the Guards so she was not likely to forget.

The Landgravine was impatient. ‘With your looks and your talents you should not be an ordinary hausfrau. And when I think of Frederick … the only heir to the throne, what will become of Denmark I can’t imagine!’

Frederick, the King’s only son, was a trial to everyone except himself of course and his cronies – and there were many of them. They consisted of the artists and writers with whom he liked to sit and drink, and his mistresses with whom he walked arm in arm through the streets; or if they were shopping he would carry their parcels for them like any bourgeois husband. Frederick was a scandal in the royal family.

But she and her little family were aloof from royalty in a way. They rarely went to Court functions simply because they wouldn’t have the suitable clothes and jewels. Even in the regiment Christian was poor. But who cared? Certainly they did not.

Life in Copenhagen was full of interest. She had enjoyed taking Fredy down to the harbour and showing him the big ships – Danish some of them, others coming in from all over the world. She would walk along the Sund pushing her son in his baby carriage like any matron of the town.

And now there would be another child.

She turned away from the window, shivering a little for it was very cold. Soon it would be Christmas. The baby should arrive a few weeks before the festival, she hoped. How wonderful that would be. Little Fredy would have his first Christmas tree and a little brother or sister as well.

The next day, which was the first of December, her child was born. It was a girl.

There was a great deal of discussion about the child’s name, between her parents that was. She was not considered to be of sufficient significance for the King or the Landgravine and her husband to think it mattered what she was called.

Louise, however, suggested that it would be a pleasant gesture to name her Alexandra after the sister of Alexander of Russia who had been married to her brother and had recently died.

Christian said this was a capital idea; he usually thought Louise’s ideas were capital. So the name was decided on. It was to be Alexandra Caroline Marie Charlotte Louise Julie.

‘Now,’ said Christian, ‘everybody can be satisfied.’

The King was kind and professed to be very interested in the child’s birth. He said she must have the silver gilt font for her baptism which was always used by members of the royal family.

Young Christian and Louise expressed their gratitude, the font was sent to the Yellow Palace and Alexandra was baptised.

How pleasant to have another child. Little Fredy was delighted. He couldn’t say Alexandra but he managed Alix and from then on the baby was known by that name.

Louise wheeled her round to the grandparents’ palace which was only a short distance away. The Landgravine was delighted with her granddaughter and had presents waiting for her and some extra money for her daughter which she presented with the comment, ‘How you manage, my dear, I do not know.’

But Louise smiled serenely and assured her mother that she managed adequately and repeated that the generosity of the King and herself made life quite easy for them.

The old Landgrave was less amiable but he loved his daughter. He was quick-tempered and somewhat eccentric; he spent hours in his enormous library reading the books in the order of which they had been acquired and placed on the shelves.

He peered at the baby and declared that she was unattractive.

‘Take it away,’ he said. ‘I don’t want to look at that ugly little thing.’

The Landgravine smiled at her daughter. ‘Don’t take any notice of Papa,’ she said.

‘But ugly, Mama!’ cried Louise indignantly. ‘Alix is beautiful.’

‘What a good thing all babies are to their mamas. Never mind, my dear, the plain babies often turn out to be the prettiest women in the long run.’

Louise was astonished. She and Christian had thought their daughter the most wonderful child on earth … as wonderful as Fredy of course.

She would not bring Alix to see the Landgrave again in a hurry.

Alix’s first memories of Rumpenheim were of the time when she was three years old. Rumpenheim was a beautiful castle on the banks of the River Main, not very far from the town of Frankfurt; the gardens were beautifully laid out, the rooms much larger than those of the Yellow Palace. Rumpenheim was like something out of a fairy tale.

Nor was it only the house and the gardens which were so entrancing. There were so many people staying at the castle and they all knew each other and at reunions they greeted each other with demonstrations of great affection. When Alix was introduced to them, they kissed her, gave her presents and talked to her about Copenhagen and the Yellow Palace and the Sund.

Who were these people? she asked her mother.

Louise, who liked her children to ask intelligent questions, replied that they were all members of her family and the reason they came to Rumpenheim in the summer was that Louise’s grandfather, the Landgrave of Hesse, had left the castle to his family on the condition that, during the summer months, some members of the family were always at the castle.

What a wonderful grandfather he must have been! commented Alix.

Her own family had grown in the last few years and she had a little brother William (called Willy) and there was a new baby girl, Dagmar. She loved them all dearly and it was a wonderful cosy feeling to belong to such a family.

At Rumpenheim was her cousin Princess Mary of Cambridge, who lived in England and was very attractive in Alix’s eyes. She seemed quite old, being thirteen, and she and Alix took to each other from the start. Mary asked permission to wheel the baby Dagmar in her carriage about the grounds and this was given; so while Mary wheeled Dagmar, Alix would trot along beside her and sometimes Mary would lift up Alix and set her in the carriage opposite Dagmar and push them both.

Because Mary was that wonderful being, not quite an adult and certainly not a child, Alix could feel less restricted in her company than she did in that of grown-ups and at the same time draw on that inexhaustible fund of knowledge which seemed to be Mary’s.

Mary explained the complicated ties which made them related. Her ancestor King George III of England had had fifteen children, nine sons and six daughters; one of these sons was Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge. He married Princess Augusta, who was the daughter of Frederick, Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel. It was this Frederick who had given Rumpenheim to his family. Frederick’s eldest son had married Alix’s mother’s mother. So Alix would see the family connection between herself and Mary.

It was very complicated for the little girl to understand but it gave her such a nice warm rich feeling to know that Mary Adelaide was a kind of cousin and that there would be many more summers spent at delightful Rumpenheim.

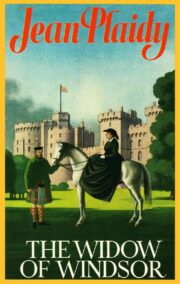

"The Widow of Windsor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Widow of Windsor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Widow of Windsor" друзьям в соцсетях.