Oh yes, it was good for the children to be together and although the girls had married abroad they could come home fairly frequently. It must be very pleasant for Alice to be in England for that poor Louis of hers was not so comfortably off as one would have liked.

I hope I was right to agree to the marriage. What would Albert have done? This was the Albert season and she sat brooding on that terrible time when he had gone to Cambridge in dreadful weather and come home to her so ill.

There was no one like him. There never would be, Blessed Angel that he was. How fortunate she had been to have twenty years of her life with him – but having known such perfection it was harder to bear his loss.

She heard that Bertie had gone up to Scarborough to Lord Londesborough’s place accompanied by Lord Chesterfield. Alix had stayed behind. The Queen could imagine what gay parties there would be up there. Oh dear, how different he was from Dearest Albert!

A week or so later there was disturbing news. The Prince of Wales had left Scarborough and was at Marlborough House and Lord Chesterfield had been taken very ill. A few days later the Prince was ill.

Bertie left London because he had desired to be at Sandringham and when he arrived there his illness had been diagnosed as typhoid fever.

The Queen could not believe it. Bertie stricken with typhoid fever, the disease which had killed his father ten years ago and at precisely the same time!

It was like a horrible pattern – a judgement.

She felt that the train would never arrive; it was snowing; she sat brooding, thinking of that terrible time ten years ago.

Brown was beside her. ‘We’re there,’ he said gruffly. He fastened the cloak about her. ‘Can’t you stand still, woman?’ he demanded, and she smiled faintly; poor Brown, he was upset because he knew she was.

The carriage was waiting. Brown helped her in and off they went to Sandringham.

The place looked gloomy. She glanced up at it; she did not like it – fast clocks and fast parties. But he was ill now – her eldest son, sick as his father had been.

Lady Macclesfield, that good faithful woman on whom Alix relied, came forward to curtsey.

‘My dear,’ said the Queen, ‘what is the news?’

‘Very bad, I fear, Your Majesty.’

‘And the Princess?’

‘She is with the Prince.’

The Queen nodded.

‘It cannot be typhoid.’

‘I fear so, Your Majesty. And Blegge the groom who accompanied His Highness to Scarborough is suffering from the same disease. They must have caught it there.’

‘You had better take me straight to him.’

Lady Macclesfield inclined her head.

‘And the Princess, how is she taking it?’ asked the Queen.

‘The Princess is wonderful,’ said Lady Macclesfield fervently.

Alix had come to the door of the sickroom with Alice.

‘My dearest children,’ said the Queen with tears in her eyes, ‘what a blessing that you are together at this time.’

She kissed them both and they took her in to see Bertie. He looked unlike himself with the strange glazed look in his eyes and the unnatural flush on his cheeks.

Oh dear God, she thought, it is so like that other nightmare. And it is soon to be the 14th of December.

The very best doctors were attending him – not only the Queen’s favourite William Jenner but Dr William Gull, Dr Clayton and Dr Lowe. The whole country waited for news as the fever soared. Bertie’s failings were forgotten; he had become ‘Good Old Teddy’. He was a jolly good fellow; he liked women; he had a mistress or two, that only showed how human he was. He was a good sport; he was the sort of man they wanted to be King – and he was sick with the typhoid fever.

Forgotten were the grudges against the royal family. The Queen was with her son who was dying of the dreaded fever which had killed his father, and in the streets crowds waited eagerly for bulletins of his progress to be issued. The question on everyone’s lips was ‘How is he?’ He was better; then he was worse; there was some hope; there was no hope. Everything was forgotten but the dramatic illness of the Prince of Wales. The fact that the 14th of December was fast approaching seemed significant. It was more than that – it was uncanny.

During one of the more hopeful periods Alix went to St Mary Magdalene’s Church at Sandringham, having first sent a note to the vicar to tell him she would be there. She wanted him to pray for the Prince that she might join in but she would not be able to wait until the service was over for she must get back to his bedside.

The church was crowded and there was a hushed silence when the Princess, wan with sleepless nights and anxiety, appeared. All joined fervently in the prayers. But, commented the Press, Death played with the Prince of Wales like a panther with its victim. But while the Prince lived there was still hope. Alfred Austin, the poet, wrote the lines by which he was afterwards to be remembered:

‘

Flashed from his bed, the electric tidings came,

He is not better; he is much the same

.’

Alix, with Alice and the Queen, were constantly in the sickroom but Alix did not forget poor Blegge and made sure that he had every care and attention. Alice was a great help; quiet and efficient and having had some practice in nursing during the wars, she devoted herself to her brother and gave that little more than even a professional nurse could have given. Alix thought she would never forget what she owed her sister-in-law. The Queen, in times of real adversity, was always at her best. She would sit quietly behind a screen in Bertie’s bedroom, not attempting to interfere, only to be there in case she could be of use.

It was the 13th of December – the day before the dreaded 14th – and Bertie had taken a turn for the worse. It was a repetition so close that it was eerie.

The doctors were despondent; it was clear that they thought there was no hope. Bertie often lay as though in a coma; at other times he would throw himself about and utter incoherent ravings.

Alix said: ‘Dear Mama, you must get some sleep.’

‘Not yet,’ said the Queen. ‘After … tomorrow.’

‘Mama, it is all over,’ said Alix.

‘Oh no, my dear child,’ replied the Queen firmly. ‘When my dearest Albert was so ill I never gave up hope.’

‘But it was no use, Mama. He died. Blegge has died, Lord Chesterfield has died. And now …’

‘My dear Alix, you must be brave. He is still with us.’

She tried to comfort Alix. The poor child was almost at breaking point. It was the 13th – and everyone seemed certain that Bertie was going to die on the anniversary of his father’s death.

‘Oh God, spare my beloved child,’ prayed the Queen.

Through the night of the 13th she waited and when the 14th dawned she was filled with a terrible apprehension.

Everywhere the tension was felt; it was as though the whole nation held its breath.

The 14th. Ten years to the day. There she had sat by his bedside and he had said: ‘Es ist das kleine Frauchen’ and she had asked him to kiss her. She remembered how his lips had moved so that she knew he had heard what she said.

She had sat there while everything that was worth while in life had slipped away from her; and she had plunged then into such utter desolation that she had not before known existed.

And now their son was dying. Poor wayward Bertie whom she had never loved as she should have. He had been a backward child and a disappointment to Albert who had so wanted a clever son. Albert used to worry so much about Bertie’s coming to the throne and not being fit for the heavy responsibilities. Had they always been fair, always kind to Bertie?

It was too late for such thoughts now. In any case Bertie was a man and he had grown far from his mother; the way of life he chose was alien to her, as hers was to him.

But she remembered that there had been moments in his childhood when she had loved him; and he had been so popular with his brothers and sisters, and usually good-tempered. She thought of his pushing his little wheelbarrow in the gardens at Buckingham Palace and Windsor; playing with his bucket and spade at Osborne, or riding his pony at Balmoral.

Alix loved him; his children adored him; there would be many to grieve for poor Bertie.

Dr Gull came to her; there was complete despair in his face. She could not bear to ask how Bertie was; she could not bear to go to his bedside, for there she could not help but see that other face; she could not shut out the echo of his words, ‘Gutes Frauchen.’

Oh, beloved Albert, dead for ten years. Am I to lose our son on the anniversary of the darkest day in my life?

A miracle had happened. On the fatal 14th Bertie had come as close to death as it was possible for anyone to do and live. All day long he had seemed to be sinking fast and even the doctors had lost hope.

The Queen implored Dr Gull to tell her the worst but he only shook his head because he could not bring himself to say, ‘The Prince is dying,’ which was what he believed to be the truth.

He left the sickroom and paced up and down the terrace. Only a short while now, he thought; and even he felt himself caught up in that fatalism which had been accepted by almost everyone else. The Prince was going to die on the 14th.

One of the nurses came running out on to the terrace.

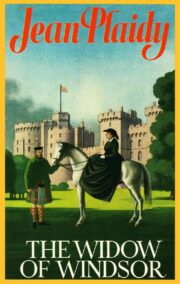

"The Widow of Windsor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Widow of Windsor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Widow of Windsor" друзьям в соцсетях.