Vicky arrived with her children and she too was horrified by the ascendancy of John Brown.

Trouble came to a head when a band of musicians who had been playing for the servants to dance Highland reels irritated Alfred who ordered the music to stop. Brown wanted to know why the musicians had stopped playing and was told by the servants that the Duke of Edinburgh had ordered it.

‘It’s nae his place,’ declared Brown and commanded the musicians to start up again.

Alfred, discovering that his order had been countermanded by Brown, was furious. He demanded an apology from Brown who refused to give it.

Alfred stormed into his mother’s apartments. This was intolerable, he told her. He had been insulted by a servant.

The Queen listened and said: ‘Brown was in charge of the servants’ dancing. You should not have interfered.’

‘This is monstrous,’ cried Alfred.

‘Are you telling me that I don’t know how to manage my household?’

‘Certainly not, Mama, but this man Brown gives himself such airs. I think he’s drunk … with either spirits or power. His position here is invidious.’

‘What are you talking about, Alfred? Brown suits me very well and brings more comfort into my life than a number of other people.’

‘No man on board my ship would be allowed to behave as he does.’

‘Pray remember,’ said the Queen, ‘that this is not a ship but a royal residence and you are not the captain of it, but I happen to be the Queen.’

Alfred went off grumbling.

Young Wilhelm behaved very badly, making a scene because he was expected to sit in a back seat in the pony carriage bowing to all the people as he passed as though he were their sovereign. He really was becoming very arrogant and he had been extremely rude to Brown who made no effort to hide his dislike of the boy.

One day Vicky’s daughter Charlotte was with the Queen when Brown came in and the Queen told the child to say good morning to him.

‘Good morning,’ said Charlotte with a curt nod.

‘That won’t do,’ said the Queen. ‘Brown expects you to shake hands with him.’

‘I can’t do that, Grandmama.’

‘What do you mean, child? You can’t do that!’

‘Mama says I must not be too familiar with the servants.’

The Queen grew pale with anger.

‘Dinna fash yersel’, woman,’ said Brown. ‘And don’t blame the wee lass. It’s the way they’ve brought her up.’

The Queen sent for her daughter.

‘I am astounded,’ she told her. ‘Charlotte has just behaved in a shameful manner.’

‘But what on earth has the child done, Mama?’ asked Vicky.

‘I have rarely been so ashamed … that a granddaughter of mine could have behaved in such an arrogant, ill-mannered way. She should be whipped and sent to her room and I should insist on this being done if I did not know that she is not to blame. I cannot understand how you young people can expect your children to behave like ladies and gentlemen when I consider the way in which they are brought up. If Dearest Papa were alive he would be so distressed.’

‘But, Mama, I cannot understand what she has done to make you so angry.’

‘She refused to shake hands with Brown … to his face. She said you had forbidden her to be too familiar with servants.’

‘But, Mama, I have forbidden her and Brown is a servant, and she was absolutely right to refuse.’

‘Papa and I brought up you children to show tact and charm to everyone … the highest and the lowest. And I would have you know that I told her to shake hands and she disobeyed me. Did you bring her up to disobey her grandmother and the Queen?’

‘Of course not, Mama.’

‘Well, that is what she did.’

‘The children have always been made aware of your position, Mama, but I and Fritz have always been very anxious to instil in them not to be familiar with servants. That can be very dangerous.’

‘Brown is not an ordinary servant.’

‘We know that well, Mama.’

‘And I will not have him treated as such. During my illness he has been my great comfort. I get precious little from some of you children.’

‘Poor Charlotte,’ went on Vicky. ‘It is a little difficult for her, you know. You would not have her mixing with the servants, I’m sure; and yet she is supposed to treat Brown as though he is … the Prime Minister at least.’

‘That is a ridiculous statement. Brown has never been treated as the Prime Minister. Brown is a very good friend. Papa noticed him and singled him out for special service.’

‘For service, yes,’ said Vicky.

‘And very good service he gives.’

‘We none of us have doubted that, Mama, but you must be aware that there is a good deal of comment concerning Brown’s position in your household and surely in view of the present unrest everywhere even you must be aware that this is not a good thing.’

‘Even I? Are you suggesting that I am less aware of what is going on than others!’

‘You do shut yourself away, Mama, and you must admit the people are getting very restive and there is a certain uneasiness. Mr Gladstone …’

‘Pray don’t talk to me about that man.’

‘He is your Prime Minister, Mama.’

‘It was never my wish that he should be.’

‘But it is the people’s wish.’

The Queen was angry. How dared her daughter presume to dictate to her! This was intolerable. She began to speak; she talked of the lack of sympathy she received from her children. Alfred and Vicky should have been a comfort to her and what happened? They came down and tried to disturb her household. Since Dearest Papa had died where could she turn for comfort? Because she had a good servant they would like to take him away from her. She had had a sympathetic Prime Minister and in a few months time he was replaced by Mr Gladstone. She felt ill and lonely. Her grandchildren disobeyed her; her children conspired to disrupt her household. She would be rather glad to be lying in the mausoleum at Frogmore beside the only one who had ever really cared for her.

Vicky said: ‘Mama, pray do not distress yourself so …’

‘Pray refrain from giving me your unwanted advice. I wish to be alone.’

‘Mama …’

The Queen regarded her daughter stonily. ‘Surely you heard me express my wish?’

‘Yes, Mama,’ said Vicky with resignation.

‘And send Brown. I will take a little whisky. And then I shall rest.’

There was no way of warning Mama, thought Vicky. This absurd situation with Brown was growing worse rather than improving. He seemed now to be more important than the Queen’s own family.

But there was nothing to be done. That was the way the Queen wanted it and the Queen’s words were law, at least in the family.

Was there no end to trouble? What Does She Do With It? was being circulated all over the place. Royal popularity was at its lowest when one of the more radical members of Parliament, Sir Charles Dilke, made a speech which was a direct attack on the Queen. She failed in her duty, he pointed out; she lived in seclusion at Windsor, Balmoral or Osborne; she only appeared in public at times when she wanted Parliament to vote money for her family; she had a vast income and on what did she spend it? Was she hoarding it? Wasn’t it meant to be spent on ceremonies and State occasions? What was the point of having a Queen who never appeared in public? It would be much less expensive and more to the point to replace royalty by a republic.

The Queen was fuming with rage when she read the report of the speech.

Who was this man Dilke? He should be ostracised. She hoped she would never be asked to meet him. He was obviously a scoundrel.

Mr Gladstone was upset. He was soon on with the old theme. If she would only come out of retirement … if she would be seen in London … it would make all the difference. It was true that she was in communication with her ministers, that she worked on state papers, but a Queen must not only do her duty, she must be seen to do it.

‘I shall do as I wish,’ she said. ‘Those who think that I shall be frightened by this man Dilke have made a very grave mistake.’

She refused to brood on it. It was getting near the end of the year and there was one day which she dreaded more than any other, the 14th of December, the day when Albert had died. Ever since that day ten years ago his memory had been kept fresh; every year when the 14th came round she stayed alone in her room and thought of him and then went to the mausoleum and meditated on his virtues and the great loss his going had brought her.

She was brooding on this when a letter arrived from Alice who was staying with her children at Sandringham with Bertie and Alix.

Sandringham, thought the Queen. Bertie and Alix were too often there, and by all accounts giving very gay parties. Bertie liked to entertain and the entertainments there were said to be lavish. She was concerned by his love of the gay life and Alix could not like it either. She believed, though, that Bertie had a little to vex him in Alix’s way of never being at a place on time. Bertie had ordered that all the clocks at Sandringham should be half an hour fast so that Alix should be helped to keep her appointments. How ridiculous! Alix would soon discover that the clocks were fast and be as late as ever. The Queen disliked clocks to be fast. ‘After all,’ she said, ‘it is a lie.’

She was glad that Alice was at Sandringham. There was something very gentle about Alice and she and Alix had become such good friends.

‘It’s the first time in eleven years that I have spent Bertie’s birthday with him,’ wrote Alice. ‘Bertie and Alix are so kind and give us such a warm welcome showing how they like having us …’

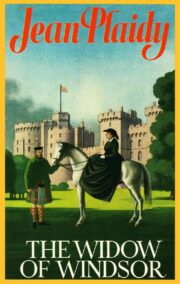

"The Widow of Windsor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Widow of Windsor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Widow of Windsor" друзьям в соцсетях.