There was great delight in the Wales’ nursery when the parents arrived. The children ran around them shrieking, Eddy pushing Georgie aside so that he could reach his mother first. Alix picked him up and kissed him fervently. She couldn’t help it but Eddy was her favourite, because he was her firstborn, she supposed. Then she picked up Georgie and hugged him just in case he had noticed.

‘Come and look at my bear,’ said Georgie.

‘No!’ cried Eddy. ‘Come and look at my donkey.’

‘I can look at them both,’ said Alix.

‘Papa too,’ demanded Eddy.

‘Papa of course,’ replied Bertie.

One of the footmen had made them each a boat which they could sail in the bath. It was the greatest fun; they could not wait to show their parents.

And Bertie soon had a boy on each knee telling them about his strange adventures at the great Pyramids and how they had looked straight into the face of the Sphinx. They had ridden on camels over the sand and he must draw a camel for them because it was really a strange beast.

Soon he was drawing camels while the boys watched intently.

They should ask the kind footman who had made the boats whether he could make camels for them, said Alix.

The boys leaped about with excitement, so delighted were they to have their parents back, and because they jostled Louise out of the way a little, Bertie promised her that on her next birthday he would take them all to the circus.

‘Will Mama come?’ Georgie wanted to know.

‘We shall all go, the whole family. Perhaps Victoria is too young, but everyone else shall go.’

Then he told them about circuses and gave an example of the various noises animals made. Alix put her fingers to her ears. ‘I can’t think what Grandmama England would say,’ she commented.

‘That’s Gangan,’ said Georgie.

‘I hope you were good boys when you were with her.’

‘Oh yes,’ Georgie told her. ‘We had to be because she’s the Queen.’

That day was devoted to the children and at bedtime Alix herself put on a flannel apron, bathed them and took them to bed.

Eddy put his arms about her neck when she tucked him in.

‘I wish you came home from travels every day,’ he said.

Then it was the turn of George and Louise.

The Queen’s birthday dawned. Fifty years old. What a great age! And how different were birthdays now from what they used to be! They were at least a time for remembering and as she lay in bed she thought of waking in Kensington Palace on a birthday morning and wondering what her presents would be and thinking what a great age she was when she was sixteen. So very long ago, in the days when she was so inexperienced and foolish yet aware of a great destiny; and it had taken Albert to teach her good sense, to make her see how she must act. How she missed him! Would she never recover from his loss?

Life would be so much easier if he were here to help her bear it. She needed him to advise her, to stand beside her and support her, to help her with the children too. They were a constant anxiety. Vicky would be Queen of Prussia one day as Albert had always wanted, but could even he have foreseen what conflict would be in the family? Alice always seemed to be in difficulties and she did not think Louis was a very strong man. They had always known that Bertie was wild – Alfred too. In truth apart from the fact that Bertie was Prince of Wales and therefore more vulnerable, Alfred gave greater cause for alarm. There had been that disgraceful affair in Malta; after that he had declared he was in love with a commoner. Really, there was going to be trouble with Alfred. Lenchen, of course, was married now and how she missed her and it was not very gratifying to remember that her husband, Christian of Schleswig-Holstein – that ill-fated place – was so poor that he found it difficult to support his wife and family. Louise might marry Lorne although it was hardly suitable, the dear young man, whom the Queen liked very much, not being royal. Arthur gave her less cause for anxiety than any of them; he was so like Albert and she was sure that if that Beloved Being could see his son today he would be gratified. No, she did not believe Arthur would cause her anxiety. Leopold was a constant source of it – poor child, he was the only one of her children who was not healthy. It was a pity for if Arthur had inherited his father’s angelic nature, Leopold had inherited his brains. He had been so ill recently that she had feared they were going to lose him, but he had recovered and she had begged him to take care. Then there was Baby Beatrice – not such a baby now being twelve years old, but she would always be Baby and, perhaps because Dearest Papa had not been there, was just a little spoiled.

A fiftieth birthday was indeed a time for brooding. They would all come to see her today and she would talk to them about Dearest Papa’s virtues and how different it would have been if he had been with them on this day.

Thinking of him she remembered a difference of opinion they had had when he wanted to make their circle more intellectual. He had thought it would be interesting for her, and she had refused. She had feared that ‘those people’ would talk over her head. How foolish she had been and how long it had taken her to learn her lessons under that kind and tender guidance.

But now that she herself had written a book – ‘Fellow author’ Disraeli had called her – she felt that she would like to meet people of literary talents. She had found Disraeli’s conversation most enlivening and she believed he had not been bored with hers. Then there was Sir Arthur Helps who had edited her book for her. He was also a very interesting man.

She had already met Lord Tennyson because Albert had said he was a great poet and she had wanted him to know how In Memoriam had comforted her.

Sir Arthur talked to her about Thomas Carlyle and when his wife died the Queen sent personal condolences. Later she met Carlyle and the poet Browning.

She told Louise that she was going to read some novels and she read Thackeray and George Eliot; but the books which appealed to her most were those of Charles Dickens.

‘So feeling,’ she said.

In November a daughter was born to the Prince and Princess of Wales. She was christened Maud Charlotte Mary Victoria.

This was Alix’s fifth child. She was delighted with her family and wished that she could become an ordinary housewife so that she could devote herself to them exclusively.

Bertie stared down at the paper in his hand. He could not believe it. This simply could not happen to him! How dared they order him to appear in court! How dared they presume … how dared they suggest …!

He felt sick. He wanted to shut himself away. He wanted no one to know of this until he had decided what to do. It was true that Lady Mordaunt had been a friend of his; he had called on her when her husband was away; he had enjoyed several delightful meetings when the two of them had been alone; she was very pretty and twenty-one and he had thought her charming.

And what had she done? She must be mad. Yes, that was the answer, she was mad, for she had made some sort of confession to her husband declaring that she had committed adultery with Sir Frederick Johnstone (his great friend from Oxford days) and Lord Cole, another crony and, among other men, the Prince of Wales.

The result was that her husband, Sir Charles Mordaunt, was suing for a divorce and although he did not name the Prince as co-respondent – that was reserved for Sir Frederick and Lord Cole – Bertie’s name was mentioned, Lady Mordaunt’s counsel was serving a subpoena on him and he must appear as a witness.

The Prince of Wales in the witness box in an unsavoury divorce case! What would the people say? What would Alix say? What would the Queen say?

Bertie was numb with anxiety. This was worse than anything that had happened to him. Curragh Camp was nothing to this. He could not think how to act. He must have advice and the advice he needed was that of a lawyer. He thought immediately of Lord Hatherley, the Lord Chancellor. He shivered at the thought. William Page Wood, Lord Hatherley, was a brilliant lawyer – perhaps the best in the country – but very austere. Bertie knew that for years he had acted as Sunday School teacher in Westminster, the parish where he lived. He would necessarily be unsympathetic but at the same time he would realise what a scandal could mean to the country, and he could be relied on to give the Prince of Wales the best possible advice.

Bertie was right. The Lord Chancellor listened attentively.

‘I am innocent,’ declared Bertie. ‘The lady must be insane. I am sure this will be proved but in the meantime I have received this subpoena to appear in court.’

This was a very grave situation, commented Lord Hatherley. The Prince could plead privilege but that he believed would be most unwise, for he was of the opinion that if any obstruction was placed on his Highness’s appearing in court that would be construed as proof of his guilt. He would have to appear in court, and of one thing he must make certain: the Queen must hear of this first through him. That was imperative. And no doubt, added Lord Hatherley, the Prince would wish to be the first to inform the Princess of Wales.

Bertie realised the wisdom of this and went straight to Alix, who was immediately alarmed by his downcast expression.

‘Bertie, what on earth has happened?’

‘Something terrible.’

‘The children …’

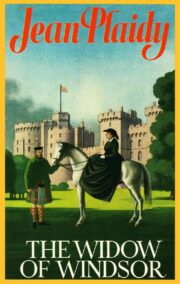

"The Widow of Windsor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Widow of Windsor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Widow of Windsor" друзьям в соцсетях.