As she sat dreaming there, thinking of her own childhood and how excited they had all been at the arrival of a new baby, she felt a wave of nostalgia for the simple life.

Bertie came in, the proud father, and he was delighted with the child. He wanted to bring Eddy and George in to see their new sister. ‘I promised them,’ he said.

And so they came and stood wonderingly by the bed, and Bertie lifted them up on to his knee and she was touched by his tenderness towards them. Bertie had suffered in his own childhood and he was going to make certain that he was as different a father from his own as it was possible for a man to be. The boys loved him with a devotion which fear could never have put there and he charmed them in his good-natured way exactly as he did the people whom he met.

But it was their mother who had first place in their hearts and Eddy was apprehensive that the newcomer might take up too much of her time and affection and Georgie was feeling the same.

How she wished that she could have devoted her time entirely to them. However, for a time, she could forget that she was the Princess of Wales and enjoy being a mother.

So she talked of the new baby and showed her to her little sons and even Louise was carried in from the nursery to join them.

When the children had gone Bertie sat with her for a while and he said that what she needed was a good long holiday away from everything.

Her eyes sparkled. ‘How I should love to go to Copenhagen and take the children with me. I’m longing to show them Rumpenheim and Bernstorff and I know my parents would love to see the babies.’

Bertie grimaced inwardly at the thought of Rumpenheim and Bernstorff; they were so dull and his parents-in-law didn’t know how to give the kind of parties he enjoyed, but he pretended to be enthusiastic. While Alix and the children were in Denmark he might slip off somewhere else – perhaps even to his delightful Paris.

‘Copenhagen yes,’ he said. ‘But I meant a long leisurely tour – say to the Middle East … somewhere where you can enjoy the sun and get rid of all those rheumaticky pains.’

‘It would be very pleasant, Bertie,’ she said. ‘Is it possible?’

‘I’m sure there’d be no difficulty from the P.M.,’ said Bertie. ‘Nor any of his colleagues. Of course, there is Mama.’ He grimaced openly. ‘You can imagine the dismay such a suggestion would rouse from that quarter. I have already put my foot down about the races. Really, Mama is quite cut off from real life. What can she know about what the people expect shut away with only that odious Brown to talk to?’

‘She’ll not agree, I’m sure,’ said Alix.

‘Leave it to me,’ said Bertie. ‘You’re going to show your parents the children, I promise you.’

The following month the new baby was christened Victoria Alexandra Olga Mary; her sponsors were headed by Queen Victoria, the Emperor of Russia, and the Queens of Greece and Denmark.

The Queen had moved a little out of seclusion that summer. She had held the first Drawing Room at Buckingham Palace since Albert’s death, had given a party in the grounds of the Palace and reviewed twenty-seven thousand volunteers in Windsor Park. This had been achieved by the gentle persuasion of Mr Disraeli. In August following the christening of the new baby she went to Switzerland.

‘No fuss,’ she had said. ‘Unlike Bertie I like to go about incognito.’ So she travelled as the Countess of Kent, stayed at the Embassy in Paris and was rather pleased when the Empress Eugénie came to see her without any formality; then she went to Lucerne and rented the Villa Pension Wallace which was right on the lake and charming. She spent a very pleasant week or so there with John Brown in attendance driving her when she wished to be driven, taking care of her comfort generally; and when she returned home she went almost immediately to Balmoral.

Some time before she had discussed with Brown the possibility of finding a little house where she could enjoy even greater seclusion than she did at Balmoral, for Balmoral was in fact a castle and there were so many servants and it was impossible to live simply as she so often longed to do.

Brown knew the spot. It had been a favourite one for Prince Albert who had often gone to the Loch Muick; it was isolated and she would be sure of not being worried there. So she built a little cottage there where she could live with just a few servants – those who were old friends like Brown and Annie MacDonald, who could forget that she was the Queen and treat her without that homage which she felt was replaced by loyalty and love.

‘This will be somewhere which will not be haunted by him,’ she said. ‘Somewhere entirely new which he has had no hand in building.’

It was a beautiful spot, known as Glassalt Shiel, which meant Darkness and Sorrow, and that, she said, was so appropriate to her mood. She could never look on that scene without experiencing a great excitement. The scenery was almost terrifying in its grandeur and she would stand for hours watching the Glassalt burn falling headlong down the mountainside into the forbidding Loch Muick.

So she had her house – her ‘Widow’s House’ she called it and although members of her family tried to dissuade her from living even for a short while in such a lonely spot, she did find to some extent what she sought there – peace.

The Queen was at Glassalt Shiel when she received a note from Bertie suggesting that Alix needed some relaxation and that she wished to take the children to see their grandparents in Denmark. The six months’ tour of Europe and the Middle East had been voted desirable by the government but the Queen could not approve of Alix’s taking the children out of the country.

She wrote to Bertie: ‘They are the children of the country, which seems to have been forgotten, and while you and Alix are away they should be left in the care of one person only and that is the Queen.’

It was rather selfish of Alix to wish to take them with her. She was going to see her parents. That should be enough for her.

Bertie, always bold when he did not have to come face to face with his stern mama, wrote back in the vein he was beginning to adopt. Alix was certainly not selfish, he replied. She was devoted to her children and he could not understand why obstacles should be put in the way of a proud young mother who wished to take her children to see her parents.

The Queen – always fair – saw the point of this and decided that the three elder children might go; it was of course impossible for such a young baby to travel. At the same time the Queen criticised the way the Wales children were being brought up.

‘Papa always believed in discipline,’ she wrote. ‘It is an absolute necessity in the bringing up of children. I fear, Bertie, that your children are allowed to run wild, and what the result of that will be I cannot imagine.’

Bertie, bold from afar, hinted that it had not always had the desired effect and that neither he nor Alfred who had been submitted to it had turned out very satisfactory from her point of view. He believed that if children were treated severely they grew shy and instead of loving their parents feared them. Of one thing he was determined, his children were not going to be afraid of him. They were not now and they never should be.

The Queen could do nothing. Bertie had always been unmanageable; and she had to admit that Eddy and George were two dear little boys even though there was such a lack of parental control.

Meanwhile Alix and Bertie set off with the three elder children and after a stay in Copenhagen where they had spent Christmas the children were sent home while their parents continued their tour visiting Egypt, Russia and Greece.

The Queen was at Balmoral while the general election was taking place. She would not believe that the country could really pass over Disraeli for the sake of Mr Gladstone although Mr Disraeli had feared this would be the case; and she was very despondent when she heard that Mr Gladstone’s government were in power with a majority of one hundred and twenty-eight.

Now she would have to return to London and what was worse send for Mr Gladstone and ask him to form a ministry, at the same time saying good-bye to dear Mr Disraeli.

She would not behave as she had in the past when Lord Melbourne had resigned; she understood that she had been rather foolish then; Albert had taught her that this was something she had to accept. It was none the more palatable for that.

When Mr Disraeli came to see her she almost wept with sorrow and anger.

This was going to be a terrible wrench she feared; she felt such confidence in him; and to think that he was to be replaced by that unsympathetic Mr Gladstone was most upsetting.

Disraeli said that they must accept this trial and hope for better things.

‘It is the only thing left to do,’ said the Queen.

She received Mr Gladstone coolly. He was quite humble and she could not complain that he did not treat her with due respect, but he was so dull and made such boring speeches that she felt as though she were a public meeting. There was a slight compensation for the loss of Mr Disraeli because some of Mr Gladstone’s colleagues were good friends of hers. She had always been fond of Lord Clarendon who was now the Foreign Secretary as well as Lord Granville who was the Colonial Secretary; and with the Duke of Argyll who was the Secretary of India she was on terms of affection. As a matter of fact Louise and Argyll’s son, the Marquis of Lorne, were very friendly, and there was a possibility that they would wish to marry. If they did she would not stand in their way. She was so tired of all the family squabbles and members of it fighting on different sides in these dreadful wars. At least if Louise married Lorne they would be of one nationality; and she had always been especially fond of the Scots.

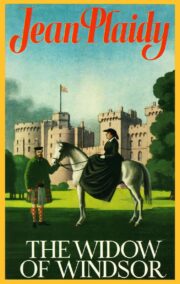

"The Widow of Windsor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Widow of Windsor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Widow of Windsor" друзьям в соцсетях.