His neglect of the Princess of Wales could not go unnoticed particularly as he was seen late at night in the company of ladies indulging in the highest of spirits which was hardly seemly when the poor Princess of Wales was an invalid.

Alice, now back in Darmstadt, was shocked by the stories which were filtering through. As was to be expected, Vicky was greatly alarmed. There were such scandalous reports of Bertie’s conduct, she wrote to her mother. Bertie was so flirtatious – and perhaps that was a mild way of expressing it; moreover he was gambling too heavily. He must be persuaded to stay away from the races.

The Queen wrote back firmly. She knew Bertie’s weakness. Dear Papa had known it and had done his best to curb it right until the end. It was always the same when Bertie was on the continent – not that his behaviour was any better at home, but it was easier to keep a rein on him there. She wrote to Bertie. He must stay away from those places where he could not be seen without losing his character.

Bertie wrote back jauntily – he could be flippant when he was away; it was when he was faced by that stern Majesty that he was nonplussed. ‘It is Vicky who has written to you. One would imagine she thought me ten years old instead of twenty-six.’

Bertie ignored the warnings.

Alix, aware of the scandal, was not very happy. She missed the babies – they were her great consolation, she was realising. It was unpleasant to have to suffer the pains of her limbs and that of humiliation besides, for there was no doubt she was humiliated. She loved Bertie. She had determined to from the beginning and it had not been difficult, for Bertie was always so charming to her. She had now to face the fact that Bertie could never love one person wholeheartedly. Bertie’s restricted childhood had resulted in a feverish desire to catch up with the good things of which he had been deprived for so long; and Bertie’s idea of the best in life did not agree with Alix’s. She liked the occasional ball, the banquet; she liked wearing her beautiful clothes and she enjoyed the admiration which had come her way since she had been Princess of Wales; but in her heart she knew that the really important things in life were not to be found at glittering balls and magnificent banquets and among friends who gushed admiration, respect and homage. Life in the Yellow Palace had taught her that and sometimes she thought sadly of all the simple pleasures of that comparatively humble household and sighed for them. She could find them in some measure in her nursery. The children’s growing dependence on her; the delight with which she was received in the nursery – these were the real joys of life. If only Bertie had agreed with her then they could have begun to build up a real happiness.

She was disappointed in her marriage, but she must not be foolish. She must take what she had and be grateful. No one, she supposed, could attain the complete ideal.

So she tried not to care too much as the scandals about Bertie’s gay life reached her; she never mentioned them to him and for this he was grateful; he loved her – as much as he was capable of loving a wife. She must be content with that.

Often she thought of her family and all the sadness which had come to them in the last few years. How was Dagmar faring in Russia? Was she happy? She knew that Willy had his trials in Greece. And dear Papa and Mama, how they had suffered!

To be young again; to be so poor that they made their own dresses; to change the new merino when one came in for fear of getting it spotted – how desirable that state of affairs sometimes seemed; to be a girl again, very poor, living in the heart of a family of which every member was more important to the others than all the riches and pomp of the world!

One must be content with less than an ideal. She had to keep repeating that to herself. She would try not to think of Bertie’s infidelities but one thing she would not do was show friendship to the Prussians who had treated her poor country so badly. When the Queen of Prussia called at Wiesbaden to visit the Prince and Princess of Wales, Alix refused point-blank to see her.

Bertie tried to remonstrate. ‘It’s important, Alix. It’s just a matter of being polite to them for a few minutes.’

‘Polite!’ she cried, her usually mild eyes stormy. ‘But I don’t feel polite to the people who have done their best to ruin my parents and my country.’

‘It’s not the monarchs. It’s their governments.’

‘They represent their country and I could never face my parents if I received them as friends.’

‘Come, Alix, be reasonable.’

‘No, no, no!’ declared Alix.

Bertie did not insist. He was always diffident about showing his authority. If there was a violent disagreement between them she might refer to those amatory adventures of which she must have heard hints. They must never be mentioned; while they were not it was as though, when they were together, they had not existed. So Bertie was patient and kind; and he explained to the King and Queen of Prussia that Alix had suddenly become so unwell that she was confined to her bed and unable to see them.

It was hardly likely that such an insult to the King and Queen of Prussia could be allowed to pass. The Queen wrote direct to Queen Victoria and told her that her Danish daughter-in-law had insulted the King of Prussia, for she did not believe that Alix had been too unwell to receive them.

How very tiresome of Alix! thought Queen Victoria. Of course she must not insult the King and Queen of Prussia! What was Bertie thinking of to allow it? Racing and other women, she supposed! Oh dear, if Albert had been alive, none of this would have happened.

She wrote to Vicky and Alice. They were at hand. They must speak to Bertie and impress on him the importance of retaining good relations with Prussia … not that she herself secretly felt very friendly towards them after the manner in which they had behaved, but it was not the fault of the King and Queen. It was that dreadful Bismarck. And Alix must be made to realise this.

Bertie was in despair. He could not bear to insist that Alix receive the Prussians. Vicky and Alice had both written to him pointing out his duty – Alice did so diffidently but Vicky was very positive. In despair he begged Alix’s mother to come and help him with the difficult task as she was with them when the imperative demand came from Vicky. Bertie and Alix must name a date when the King and Queen of Prussia could call on them.

Louise was in a dilemma. Alix could be stubborn; like most easy-going people she would drift along and then suddenly take a stand and when she did there was little hope of moving her. Moreover she had been very ill and was by no means recovered. Louise said that she would meet the Prussian King and Queen in her daughter’s place, even though it would be repugnant to her.

This would not do, wrote Vicky authoritatively. Alix must be made to receive the King and Queen of Prussia. It was necessary for Bertie to act. He sent the invitation and then went to Alix.

She regarded him stonily.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said, ‘but there was nothing else I could do. If I could have spared you that I would have done so. I understand your feelings … but the pressure was too great.’ He kissed her lightly on the top of her head. ‘It’ll soon be over,’ he comforted.

How like him! He could not really understand and although he was kind, there was just a shadow of impatience. Wasn’t she making rather a fuss over something that was not so very important?

She was silent and he went on explaining: ‘Mama insists, I’m afraid. And there’s Vicky and Alice …’

‘Those two interfering old women,’ she cried. ‘What has it to do with them!’

Bertie laughed. ‘I know Vicky behaves as though she is my governess but she’s only a year older than I, and Alice is two years younger.’

But Alix could not smile. She felt sick and humiliated.

She knew, though, that there was no help for it. The King came as arranged and her manner was so correct, although she was seething inwardly, that the King at least was not aware of her resentment.

The Queen had noticed for some time that Lord Derby was not looking well. He was after all a very old man and the tasks imposed on Prime Ministers could hardly be expected to be good for their health.

She was constantly asking him how he was and showering him with sympathy which would have been gratifying if he had not known that she was not so anxious to see him in better health as to see him in retirement.

The reason was that if he gave up office the obvious sequel would be that she must send for the man who had rapidly become her favourite politician.

She was at Osborne that February when Lord Derby came to the conclusion that he would delay no more. He wrote to her telling her of his decision and advising her to send for Benjamin Disraeli.

This she did with the utmost pleasure.

She smiled as he came into her drawing-room and she held out her hand for him to kiss. He bent over it with a flamboyant bow and kissed it with fervour. Then he made a charming speech, for he was very clever with words; he offered her loyalty and devotion. And she felt her spirits lifted as she had on that first day when Lord Melbourne had visited her and she had just become the Queen of England.

It was a moving scene and she felt more at peace, she told herself, than she had since Albert’s death.

Her new Prime Minister thereupon began to enchant her in much the same way as Lord Melbourne had. He discussed matters of state with her intermingled with amusing anecdotes about the people they knew; he assumed she would act in such and such a way because such superb intelligence as she possessed would make her realise immediately why such and such must be done.

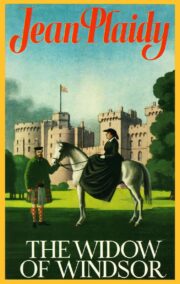

"The Widow of Windsor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Widow of Windsor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Widow of Windsor" друзьям в соцсетях.