Albert would be right because he always had been right, and of course she would wish to follow Albert in all things. Lord Palmerston might hint at the dark practices of which he suspected the Prussians might be guilty; Bertie might rave against them, it was typical of the British press to write sentimentally about Little Denmark; and poor Alix was naturally broken-hearted; but the Queen felt that Albert would believe that Augustenburg had first claim on Schleswig-Holstein and one could not be sentimental about that sort of thing.

Vicky was writing from Berlin and how could she fail to support the country to which she now belonged. What was happening in Denmark, she said, was King Christian’s own fault; he should not have taken the crown knowing what a flimsy claim he had. Of course he was dear Alix’s father and she was sorry for Alix, particularly in her present condition. It was most unfortunate; moreover, there were rumours on the continent that Bertie was rather fond of the society of ladies whose reputation was not of the best. Another trial for poor Alix! Still, that did not alter the rights of the situation.

If only dear beloved Albert had been here it would all have been so much easier to make everyone understand, and she had no doubt that he would have come up with the right solution and been able to persuade either the Prussians to desist or Christian to give way. But alas for the world, Albert was no more.

The 14th of December had arrived again – the second anniversary of his death. There was nothing else to be thought of on that day but the great emptiness that was left by his departure. She and the children would visit the mausoleum and spend some time there; and afterwards she would shut herself in her room and read her journals and mourn afresh.

Christmas was not a very happy season. Alix was sick and wretched, with the terrible Schleswig-Holstein business hanging over everything like a black cloud. In addition, her pregnancy was not proving an easy one and there were occasions when she felt really ill – a fact which she strove hard to keep from Bertie who liked everyone about him to be carefree.

Vicky was writing rather censoriously from Berlin in definitely anti-Danish terms; the Queen’s half-sister, Feodora, whose daughter was married to the Duke of Augustenburg, was vigorously on the side of the rebels; and Alix, remembering other Christmases at the Yellow Palace, longed for the old Scandinavian Jul and those days when the only tragedy in life was being late for meals and having to go without a second helping or take her coffee standing up.

On one occasion she had been unable to contain herself and had burst out in an anti-Prussian tirade before the Queen. Victoria had always been affectionate to Alix but in that moment her expression was cold and her manner regal.

‘My dear Alix,’ she said as though Alix was anything but dear to her, ‘I see that I must give orders that Schleswig-Holstein is a subject which shall not be discussed among the family in my presence.’

Alix could have burst into tears. It was all so sad and changed. Only Bertie was comforting and quarrelled with Vicky on his wife’s behalf.

But, as the Queen said, it was particularly distressing when political matters became family affairs.

Bertie and Alix stayed at Frogmore which Bertie said was less depressing than Windsor and, being in the Windsor Royal Park, was accessible to the Castle and therefore they would not offend Mama by taking up residence there.

It was bitterly cold that winter and Virginia Water was frozen over. When Alix saw it she thought of skating parties at home and declared her desire to go on the ice.

Bertie looked dubious and the Countess of Macclesfield, Alix’s chief lady of the Bedchamber, was horrified at the idea. Alix had come to rely on Lady Macclesfield who was very motherly – she had twelve children of her own – and ever since Alix’s arrival in England had been in charge of the household which was very useful from Alix’s point of view.

‘In your condition,’ said Lady Macclesfield, ‘it would be folly.’ And Alix meekly agreed.

Bertie, however, was planning a party; he was of the opinion that everything should be celebrated by a party and when ice hockey was suggested he was enthusiastic.

‘I’ll tell you what, Alix,’ he said, ‘you come and watch us. The fresh air will do you good.’

How gay Bertie was! He had forgotten all about the troubles of Schleswig-Holstein. Alix wished that she could throw off her troubles as easily as he could – although of course Schleswig-Holstein was not exactly his trouble, although she was terribly afraid that all was not going well for Denmark.

Bertie was calling wildly to his friends as he slid across the ice. She longed to join them but she was beginning to feel rather sick.

She did not want to spoil Bertie’s game by leaving the scene, so she stood there smiling and applauding and suddenly she was in pain.

She turned to one of the women and said: ‘I think I’ll go back to Frogmore now. It’s a little cold.’

At a break in the game Bertie came to her and composing her features she said that she thought she would return to Frogmore because it was rather cold.

‘It’s beautifully warm,’ said Bertie, glowing from the game; and she smiled at him.

‘It’s colder standing about. I should have been on the ice.’

‘I’m sorry you couldn’t be,’ said Bertie tenderly, but she could see he was longing to join his friends, so she left promptly and went back to the house.

It was fortunate that she did for no sooner had she entered than she was in great pain.

Lady Macclesfield came running to her.

‘Good heavens,’ she cried. ‘It can’t be. It’s two months too soon.’

But it was.

It was fortunate that a sensible woman like Lady Macclesfield was in charge. Her first act was to get Alix to bed and send to the town of Windsor for Dr Brown, a doctor who, because his practice was there, had served the royal family on other occasions. He had become well known because of this and had a good reputation.

At the same time she sent an equerry to the Castle to inform the Queen of what was happening and gave orders that a special train should leave for London to tell the Archbishop of Canterbury, Lord Palmerston and the Lord Chamberlain of the baby’s imminent arrival.

Then she went back to Alix, who was in great pain. There was no doubt that the child was about to be born and there was nothing ready for it.

Dr Brown arrived immediately and even so he was only just in time, and he and Lady Macclesfield between them delivered the child. A boy.

There were no clothes ready so Lady Macclesfield took off the flannel petticoat she was wearing, because of the intense cold, and wrapped the little boy in it. Alix was exhausted and the seven-months’ child was naturally rather feeble and would need special care.

It was fortunate that Lord Granville, a member of the Cabinet, happened to be staying at Frogmore, so that Lady Macclesfield was able to present the new baby – wrapped in her petticoat – to him. He was not the Archbishop of Canterbury nor the Prime Minister nor the Lord Chamberlain, whom custom asked should be present at a royal birth, but the circumstances of a seven-months’ child were extenuating and it was decided that Lord Granville would do on this occasion.

The Queen came hurrying over to Frogmore to see her new grandson. Such a feeble little thing, but then she had never liked little babies. And dear sweet Alix, who had had so much anxiety about her parents and that dreadful Schleswig-Holstein affair, was very weak.

Alix began to recover in a few days and holding her baby in her arms she was able to forget for a while the tragic happenings in Denmark.

Vicky wrote from Berlin, very excited by the news. She criticised the parents of the newly born child, though, and hinted that they had brought on the premature birth by their conduct. Bertie’s gay life was talked of freely and it was really rather embarrassing, she pitied poor dear Alix. But Alix herself had not taken proper care; she had kept late nights too and not rested enough. Why, on the very occasion of the birth she had been out skating.

The Queen replied she was pleased to have a grandson and it was amazing that the birth had been all over in an hour. Good Dr Brown from Windsor had done very well and they must be grateful to Lady Macclesfield who, the dear good soul, had done everything that the nurses were trained to do. It was necessary to take the utmost care of the child and keep him in cotton wool. Seven-months’ children were naturally more difficult to rear than those who had enjoyed the full period of gestation. She thought this would be a lesson to Alix and Bertie to take greater care in future.

Settled in at Frogmore the Queen thought longingly of Osborne. She disliked births but felt it her duty to be present. She told Vicky she would have liked to be with her at the birth of her children. She fancied she could be a little comfort to them and it was pleasant to be of some use in the family now that Dearest Papa was no longer there to need her.

She forgot her annoyance with Alix over Schleswig-Holstein because the dear girl looked so pretty in bed and she could always feel lenient towards people at whom it was pleasant to look.

The question of the child’s name arose.

Bertie wanted to call him Victor. It will be a change in the family, he said.

Alix liked it, too.

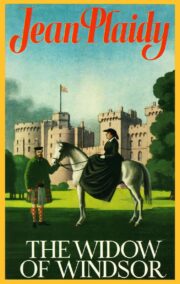

"The Widow of Windsor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Widow of Windsor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Widow of Windsor" друзьям в соцсетях.