Alix was delighted that Mary was there – so magnificent, stately, handsome and kind. She was less sure of Vicky, who was half Prussian since her marriage and of course the Prussians were not friends to the Danes. Bertie had told her that he had always been compared to his detriment with his clever sister and for that reason she felt she could never really be close to Vicky.

Mary said it had been a wonderful ceremony and Alix had been admired from all sides. Everyone had commented on her poise, dignity and beauty.

Vicky agreed that this had been so.

‘I’m sure there was only one in the chapel who didn’t admire you,’ went on Vicky, ‘and that was my naughty little son who – I saw him do it – bit both his uncles on the leg.’

‘I am sure my little brother Valdemar was equally indifferent,’ added Alix. ‘He said he would rather play with his donkey than come to my wedding.’

They laughed together, but there was an aloofness about Vicky, made more obvious perhaps by the warmth of Cousin Mary’s affection. She must remember, though, that Mary had been her friend since the days when she was three years old and they had met at Rumpenheim.

There she stood in her white silk dress and Mary exclaimed that she looked lovely.

She was glad because it was time for her to go off to Osborne with Bertie.

Chapter VII

ADVENTURE IN THE HIGHLANDS

How difficult it was, thought the Queen, to remain in seclusion when one was the Sovereign. Lord Palmerston, her Prime Minister, had never been a favourite of hers, although she had come to realise the need for a strong man at the head of affairs, and she supposed he was that. But Albert had never approved of Palmerston who had scarcely led a good life in his youth, although it was true that when he settled down and married Lord Melbourne’s sister they were devoted to each other and lived in harmony. But Palmerston’s eyes would always follow a beautiful woman speculatively and Albert had noticed it and disapproved. Every man could not of course be like her Angel, but a Prime Minister she believed should show more decorum than Lord Palmerston was accustomed to. He was referred to as ‘Pam’ by the people, who for some odd reason adored him. How unpredictable the people could be! They had never appreciated Albert. But Pam was better than Cupid, the name by which the Prime Minister had been known in his youth – for obvious reasons.

Now Lord Palmerston was warning her that there was likely to be trouble over Schleswig-Holstein, that matter which had never really been settled; this would mean of course trouble between Prussia and Denmark for Denmark would not willingly give up the provinces because Bismarck told them to.

How tiresome! And if only Albert were here, he would understand and see that something was done.

‘There are three people who understand the Schleswig-Holstein controversy,’ said Lord Palmerston. ‘The Prince and he’s dead and myself …’

‘The other one?’ she had asked.

Lord Palmerston had replied with the utmost irreverence and that rather wicked smile of his. ‘God, Your Majesty.’

She sighed for the tact and sympathy of Lord Melbourne – long since dead and only now occasionally remembered.

She was worried too about Alfred. Bertie had ceased to be such a concern now that he was married to dear sweet Alix who was so good for him. Alfred had had a very unpleasant adventure in Malta. It concerned a woman. Oh dear, she did hope the boys were not going to be tiresome in that respect. First Bertie at the Curragh Camp – and what fearful results that had had! She wondered Bertie could sleep at night for thinking of it; but she was sure he never did – think of it, that was. His sleep would be quite undisturbed. And now Alfred in Malta.

Bertie had said: ‘Oh, Mama, one doesn’t want to make too much of these things. Poor old Affie, he had to amuse himself somehow.’

She was annoyed. Bertie had too much confidence since his marriage. He was always appearing in public and Alix with him and people cheered them madly wherever they went.

‘Very commendable,’ was Lord Palmerston’s comment. ‘Makes up for your hiding yourself away, M’am, and satisfies the people.’

Lord Palmerston had always taken Bertie’s side.

But she did realise that Alfred’s affair at Malta was not of the same magnitude as his future as Duke of Saxe-Coburg. Albert had always intended Alfred to take over Ernest’s dukedom when he died.

Ernest was not in the least like his brother Albert. Oh, the irony of fate that the saint should be taken and the sinner left. One could not probe too deeply into the life Ernest had led. There were women, and debts in plenty, and no children at all, which was why Saxe-Coburg was to go to Alfred. Albert had often talked to her about Ernest. He just could not believe, he used to say, how that brother of his, with whom in his youth he had been inseparable, could have turned out as he did. But Ernest had changed from the innocent youth who had roamed the forests round Rosenau with his brother and hunted for specimens for their museum. She had always declared that when the influence of Albert was removed Ernest had gone to pieces.

The throne of Greece had become vacant and this had been offered to Alfred. This offer had thrown the Queen into a flutter. It was gratifying, of course, but Albert had always talked of Alfred as though he were the future Duke of Saxe-Coburg and she had declined the honour on Alfred’s behalf.

Ernest had immediately declared that he would take on the kingdom of Greece, at the same time retaining his Duchy of Saxe-Coburg.

This was something the Queen could not tolerate. Alfred would be expected to go to Saxe-Coburg as heir to that Duchy and govern while Ernest was in Greece. Oh dear, no. That would not do at all. Albert would have disapproved most strongly. Ernest would be the real ruler, Alfred a deputy. The affairs of Saxe-Coburg under the dissolute Ernest were in a sorry state and it was very likely that if Alfred became deputy ruler he could fall into his uncle’s ways and – more practically – perhaps be held responsible for their results.

Her Prime Minister came down to Windsor to see her rather reproachfully because she was not in London which would have made communication with her ministers so much easier. She gave him her severe and rather haughty look which seemed to amuse him, a fact of which she was aware and deplored, but of course she could not tell him that she did not like his manner. She never had liked his manner, but she had been forced to admit since that terrible and most unsatisfactory Crimean war that the country could not do without him.

He bowed over her hand. He must be nearly eighty, she thought. Quite clearly he painted his cheeks. How unmanly! And yet how could one accuse Palmerston of effeminacy? He merely wanted to pretend that he was as well as ever. She had heard that he had been seen solemnly climbing over the railing before his house and when he was on the other side, equally solemnly climbing back. A policeman watching him had very naturally thought he was intoxicated and going over to him discovered to his amazement that the climber was not only sober but the Prime Minister.

‘I just wanted to see if I still had enough agility to climb those railings and back. And I did, so you see, there’s life in the old dog yet,’ was his comment.

The story was repeated and the people of course had loved him for it and shouted ‘Good Old Pam, there’s life in the old dog yet!’ wherever he went. How strange that all Albert’s good works had gone unrecognised – or almost so – and this absurd escapade had brought Palmerston even more popularity with the masses.

What was it about him? she wondered. That air of confidence and nonchalance. He knew she didn’t like him and he simply didn’t care; his attitude reminded her constantly that it was the people who selected their rulers. And they were behind Pam.

She asked after his gout. He said it bothered him from time to time.

‘And Lady Palmerston is well?’

‘She is and will be honoured when I tell her that Your Majesty enquired.’

‘You have come over this affair of Greece of course.’

‘That, M’am, and the even more important question of Schleswig-Holstein.’

‘There is trouble brewing there.’

‘There’s always trouble brewing there. And with Bismarck in the ascendant the situation is not improved.’

‘The Prince Consort would never have agreed to Alfred’s taking the Greek throne. And I think we should strongly oppose its going to my brother-in-law.’

Palmerston seemed to agree with this opinion. He thought it was possible that one of the Danish Princes might be offered the Greek throne. He could see no harm in that.

‘You mean one of Alexandra’s brothers. Not the eldest. He will be King of Denmark.’

‘The next one perhaps,’ said Palmerston.

‘He’s so young.’

‘Princes have responsibilities thrust early upon them as Your Majesty well knows from personal experience.’

She nodded gravely.

But he had not really come to talk to her about the Greek throne. He was concerned with Prussia – deeply concerned.

Bismarck, it seemed, was the real ruler of Prussia and he was out for conquest. He was talking of a united Germany and his slogan was ‘blood and iron’.

‘Very descriptive words, Your Majesty,’ commented Palmerston, ‘and leaving us in no doubt of their meaning.’

‘William of Prussia would abdicate in favour of the Crown Prince,’ he went on, ‘but I do not think the Crown Prince is eager for it. Nor is Bismarck.’

‘My daughter and her husband don’t like the man.’

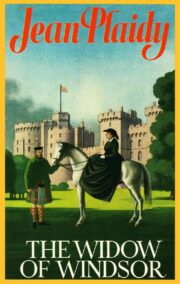

"The Widow of Windsor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Widow of Windsor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Widow of Windsor" друзьям в соцсетях.