She stops, and the hard face of the seer dissolves into the warmth of the mother whom I love. “I think you will have him, if that is what you want,” she says.

“More than life itself.”

She laughs at me but her face is gentle. “Ah, don’t say that, child. Nothing in the world matters more than life. You have a long road to walk and a lot of lessons to learn if you don’t know that.”

I shrug and take her arm and, walking in step, we turn for home.

“When the battle is over, whoever wins, your sisters must go to court,” my mother says. She is always planning. “They can stay with the Bourchiers, or the Vaughns. They should have gone months ago, but I could not bear the thought of them far from home and the country in uproar, and never knowing what might happen next, and never able to get news. But when this battle is over, perhaps life will be as it was, only under York instead of Lancaster, and the girls can go to our cousins for their education.”

“Yes.”

“And your boy Thomas will be old enough to leave home soon. He should live with his kinsmen; he should learn to be a gentleman.”

“No,” I say with such sudden emphasis that she turns and looks at me.

“What’s wrong?”

“I will keep my sons with me,” I say. “My boys are not to be taken from me.”

“They will need a proper education; they will need to serve in the household of a lord. Your father will find someone, their own godfathers might-”

“No,” I say again. “No, Mother, no. I cannot consider it. They are not to leave home.”

“Child?” She turns my face to the moonlight so that she can see me more clearly. “It’s not like you to take a sudden whim over nothing. And every mother in the world has to let her sons leave home and learn to be men.”

“My boys are not to be taken from me.” I can hear my voice tremble. “I am afraid…I am afraid for them. I fear…I fear for them. I don’t even know what. But I cannot let my boys go among strangers.”

She puts her warm arm around my waist. “Well, it is natural enough,” she says gently. “You lost your husband; you are bound to want to keep your boys safe. But they will have to go someday, you know.”

I do not yield to her gentle pressure. “It is more than a whim,” I say. “It feels more…”

“Is it a Seeing?” she asks, her voice very low. “Do you know that something could happen to them? Have you come into the Sight, Elizabeth?”

I shake my head and the tears come. “I don’t know, I don’t know. I can’t tell. But the thought of them going from me, and being cared for by strangers, and me waking in the night and not knowing that they are under my roof, waking in the morning and not hearing their voices, the thought of them being in a strange room, served by strangers, not able to see me-I can’t bear it. I can’t even bear the thought of it.”

She gathers me into her arms. “Hush,” she says. “Hush. You need not think of it. I will speak to your father. They need not go until you are happy about it.” She takes my hand. “Why, you are icy cold,” she says, surprised. She touches my face with sudden certainty. “This is not a whim when you are both hot and cold in moonlight. This is a Seeing. My dear, you are warned of danger to your sons.”

I shake my head. “I don’t know. I can’t be sure. I just know that no one should ever take my boys from me. I should never let them go.”

She nods. “Very well. You have convinced me, at least. You have seen some danger for your boys if they are taken from you. So be it. Don’t cry. You shall keep your boys close at hand and we will keep them safe.”

Then I wait. He told me clearly enough that I would never see him again, so I wait for nothing, knowing full well that I am waiting for nothing. But somehow I cannot help but wait. I dream of him: passionate, longing dreams that wake me in the darkness, twisted up in the sheet, sweaty with desire. My father asks me why I am not eating. Anthony shakes his head at me in mocking sorrow.

My mother snaps one bright-eyed glance at me and says, “She is well. She will eat.”

My sisters whisper to ask me if I am pining for the handsome king, and I say sharply, “There would be little point in that.”

And then I wait.

I wait for another seven nights and another seven days, like a maiden in a tower in a fairy tale, like Melusina bathing in the fountain in the forest, waiting for a chevalier to come riding the untrodden ways and love her. Each evening I draw up the loop of thread a little closer until on the eighth day there is a little chink of metal against stone and I look into the water and see a flash of gold. I bend down to pull it out. It is a ring of gold, simple and pretty. One side is straight, but the other is forged into points, like the points of a crown. I put it on the palm of my hand, where he left his kiss, and it looks like a miniature coronet. I slip it on my finger, on my right hand-I tempt no misfortune by putting it on my wedding finger-and it fits me perfectly and suits me well. I take it off with a shrug, as if it were not the highest-quality Burgundian-forged gold. I tuck it into my pocket, and I walk home with it safe in my keeping.

And there-without warning-there is a horse at the door and a rider sitting tall on it, a banner over his head, the white rose of York uncurling in the breeze. My father stands in the open doorway reading a letter. I hear him say, “Tell His Grace I shall be honored. I will be there the day after tomorrow.”

The man bows in the saddle, throws a casual salute to me, wheels his horse, and rides away.

“What is it?” I ask, coming up the steps.

“A muster,” my father says grimly. “We are all to go to war again.”

“Not you!” I say in fear. “Not you, Father. Not again.”

“No. The king commands me to provide ten men from Grafton and five from Stony Stratford. Fitted and kitted to march under his command against the Lancaster king. We are to change sides. That was an expensive dinner we gave him, as it turned out.”

“Who is to lead them?” I am so afraid that he will say my brothers. “Not Anthony? Not John?”

“They are to serve under Sir William Hastings,” he says. “He will put them in among trained troops.”

I hesitate. “Did he say anything else?”

“This is a muster,” my father says irritably. “Not an invitation to a May Day breakfast. Of course he didn’t say anything except that they would be coming through in the morning, the day after tomorrow, and the men must be ready to fall in then.”

He turns on his heel and goes into the house, and leaves me with the gold ring, shaped like a crown, spiky in my pocket.

My mother suggests at breakfast that my sisters and I, and the two cousins who are staying with us, might like to watch the army go by, and see our men go off to war.

“Can’t think why,” my father says crossly. “I would have thought you would have seen enough of men going to war.”

“It looks well to show our support,” she says quietly. “If he wins, it will be better for us if he thinks we sent the men willingly. If he loses, no one will remember we watched him go by, and we can deny it.”

“I am paying them, aren’t I? I am arming them with what I have? The arms I have left over from the last time I went out, which, as it happens, was against him? I am rounding them up, and sending them out, and buying boots for those who have none. I would think I was showing support!”

“Then we should do it with a good grace,” my mother says.

He nods. He always gives way to my mother in these matters. She was a duchess, married to the royal Duke of Bedford when my father was nothing but her husband’s squire. She is the daughter of the Count of Saint-Pol, of the royal family of Burgundy, and she is a courtier without equal.

“I would like you to come with us,” she goes on. “And we could perhaps find a purse of gold from the treasure room, for His Grace.”

“A purse of gold! A purse of gold! To wage war on King Henry? Are we Yorkists now?”

She waits till his outrage has subsided. “To show our loyalty,” she says. “If he defeats King Henry and comes back to London victorious, then it will be his court, and his royal favors that are the source of all wealth and all opportunity. It will be he who distributes the land and the patronage and he who allows marriages. And we have a large family, with many girls, Sir Richard.”

For a moment we all freeze with our heads down, expecting one of my father’s thunderous outbursts. Then, unwillingly, he laughs. “God bless you, my spellbinder,” he says. “You are right, as you are always right. I will do as you say, though it goes against the grain, and you can tell the girls to wear white roses, if they can get any this early.”

She leans over to him and kisses him on the cheek. “The dog roses are in bud in the hedgerow,” she says. “It’s not as good as full bloom, but he will know what we mean, and that is all that matters.”

Of course, for the rest of the day, my sisters and cousins are in a frenzy, trying on clothes, washing their hair, exchanging ribbons, and rehearsing their curtseys. Anthony’s wife Elizabeth and two of our quieter companions say that they won’t come, but all my sisters are beside themselves with excitement. The king and most of the lords of his court will go by. What an opportunity to make an impression on the men who will be the new masters of the country! If they win.

“What will you wear?” Margaret asks me, seeing me aloof from the excitement.

“I shall wear my gray gown, and my gray veil.”

“That’s not your best; it’s only what you wear on Sundays. Why wouldn’t you wear your blue?”

I shrug. “I am going since Mother wants us to go,” I say. “I don’t expect anyone to look twice at us.” I take the dress from the cupboard and shake it out. It is slim cut with a little half train at the back. I wear it with a girdle of gray falling low over my waist. I don’t say anything to Margaret, but I know it is a better fit than my blue gown.

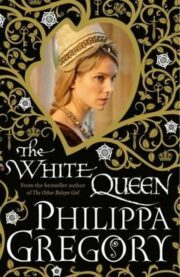

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.