“We don’t have to come out to glory, you know,” she says plaintively. “We could just go to a pleasant house, and be an ordinary family.”

“All right,” I say, as if I think we can ever be an ordinary family. We are Plantagenets. How could we be ordinary?

JANUARY 1484

I hear from my son Thomas Grey, in a letter which comes to me travel-stained from Henry Tudor’s ragamuffin court in Brittany, dated Christmas Day 1483.

As he promised, he swore to his betrothal to your daughter Elizabeth in the cathedral in Rennes. He also claimed the title of King of England and was acclaimed king by all of us. He received our homage and oaths of loyalty, mine among the others. I heard one man ask him how he could claim to be heir, when the young King Edward might be living for all we know. He said something interesting…he said that he had certain proof that the young King Edward is dead, and that his heart is sore for it, and that we should have revenge on his murderer-the usurper Richard. I asked him what proof he had, and reminded him of your pain without a son to bury, nor any knowledge of him; and he said that he knew for a fact that Richard’s men had killed your boys. He said they had pressed them under their bedding as they slept, and then buried them under the stair in the Tower. I took him to one side and said that at the very least we could place servants or suborn those who are there and order them to find the bodies if he would only tell me where they are, which stair in the Tower. I said that if we found the bodies as his invasion of England began, we could accuse Richard of murder, and the whole country would be on our side. “Which stair?” I asked. “Where are the bodies? Who told you of the murder?” Lady Mother, I lack your skills of seeing into the dark hearts of men, but there was something about him that I couldn’t like. He looked away, and said it was no good, he had thought of it already, but a priest had lifted their bodies and taken them away in a chest to give them a Christian burial, and buried them in the deepest waters of the river, never to be found. I asked him the name of the priest but he did not know it. I asked him how the priest knew where they were buried and why he put them in the river instead of taking the bodies to you. I asked him if it was to be a Christian burial then why put them in the water? I asked him which part of the river and he said he did not know. I asked him who told him all this, and he said it was his mother Lady Margaret, and that he would trust her with his life. It will be just as she has told him; he knows this for a fact. I don’t know what you make of this. It stinks to me.

I take Thomas’s letter and put it into the flames of the fire that burns in the hall. I take up a pen to reply to him, trim the nib, nibble the feather at the top, and then write.

I agree. Henry Tudor and his allies must have had a hand in the death of my son. How else would he know they were dead and how it was done? Richard is to release us this month. Get away from the Tudor pretender and come home. Richard will pardon you and we can be together. Whatever vows Henry takes in church and however many men show him homage, Elizabeth will never marry the murderer of her brothers, and if he is indeed the killer, then he carries my curse to his son and his grandson. No Tudor boy will live to manhood if Henry had a hand in the death of my son.

The end of the twelve days of Christmas and the return of the Parliament to London brings me the unwelcome news that Parliament has obliged King Richard and ruled that my marriage was invalid, that my children are bastards and that I myself am a whore. Richard had declared this before, and no one had argued with him. Now it is law and the Parliament, like so many moppets, nods it through.

I don’t make any objection to the Parliament, and I don’t command any friends of mine to object for us. It is the first step in freeing us from our hiding place that has become our prison. It is the first step in turning us into what Elizabeth calls “ordinary people.” If the law of the land says that I am nothing more than the widow of Sir Richard Grey, and the former king’s former lover, if the law of the land says that my children are merely girls born out of wedlock, then we are of little value alive or dead, imprisoned or free. It does not matter to anyone where we are, or what we are doing. This, on its own, sets us free.

More importantly, I think, but I do not say, not even to Elizabeth, that once we are living in a private house quietly, my boy Richard might be able to join us. As we are stripped of our royalty my son might be with me again. When he is no longer a prince, I might get him back. He has been Peter, a boy living with a poor family in Tournai. He could be Peter, a visitor to my house at Grafton, my favorite page boy, my constant companion, my heart, my joy.

MARCH 1484

I receive a message from Lady Margaret. I had been wondering when I would hear again from this my dearest friend and ally. The storming of the Tower that she planned failed miserably. Her son tells the world that my sons are dead, and says that his mother alone knows the details of their death and burial. The rebellion that she masterminded ended in defeat and my suspicions. Still her husband is high in favor with King Richard, though her part in the rebellion is well known. For sure, she is an unreliable friend and a doubtful ally. She seems to know everything, she seems to do nothing, and she is never punished.

She explains she has not been able to write, and that she cannot visit me herself, for she is cruelly imprisoned by her husband Lord Stanley, who was Richard’s true friend, standing by him in the recent uprising. It turns out now that Stanley’s son Lord Strange raised a small army in support of King Richard; and that all the whispers that he was marching to support Henry Tudor were mistaken. His loyalty was never in doubt. But there were enough men to testify that Lady Margaret’s agents had gone back and forth to Brittany to summon her son Henry Tudor to claim the throne for himself. There were spies who could confirm that her great counselor and friend Bishop Morton persuaded the Duke of Buckingham to turn against his lord Richard. And there were even men who could swear that she had made a pact with me, that my daughter should marry her son, and the proof of that was Christmas Day in Rennes Cathedral when Henry Tudor declared that he would be Elizabeth’s husband and swore that he would be King of England; and all his entourage, my son Thomas Grey among them, knelt and swore fealty to him as King of England.

I imagine that Margaret Beaufort’s husband Stanley must have had to talk fast and persuasively to convince his anxious monarch that, though his wife is a rebel and a plotter, he himself had never for a moment thought of the advantages that might come to him if his stepson took the throne. But he seems to have done it. Stanley “Sans Changer” remains in favor with the usurper, and Margaret his wife is banished to her own house, forbidden her usual servants, banned from writing or sending messages to anyone-especially her son-and robbed of her lands and wealth and inheritance. But they are all given to her husband on the condition that he keeps her under control.

For a powerful woman she does not seem much disheartened by her husband taking all her wealth and all her lands into his own hands, and imprisoning her in her house, swearing that she shall never write another letter and never stir another plot. She is clearly right not to be too disheartened, for here she is, writing to me and plotting again. From this I think I can assume that Stanley “Sans Changer” is faithfully and loyally following his own best interests as perhaps he has always done-promising fealty to the king on one hand, letting his wife plot with rebels on the other.

Your Grace, dear sister-for so I should call you who is mother to the girl who will be my daughter, and who will be mother to my son, she starts. She is flowery in style and emotional in life. There is a smudge on the letter as if she has overflowed with tears of joy at the thought of the wedding of our children. I look at it with distaste. Even if I did not suspect her of the wickedest of betrayals, I would not warm to this.

I am much concerned to hear from my son that your son Thomas Grey thought to leave his court and had to be persuaded to return to them. Your Grace, dear sister, what can be the matter with your boy? Can you assure him that the interests of your family and mine are the same and that he is a beloved companion to my son Henry? Please, I beg of you, command him as a loving mother to endure the troubles that they have in exile to make certain of the rewards when they triumph. If he has heard anything, or fears anything, he should speak to my son Henry Tudor, who can put his mind at rest. The world is full of gossips and Thomas would not want to appear a turncoat or fainthearted now. I hear nothing, locked away as I am, but I understand that the tyrant Richard is planning to have your older girls at his court. I do beg you not to allow them to go. Henry would not like his betrothed to be at the court of his enemy, exposed to every temptation, and I know you as a mother would feel such revulsion to have your daughter in the hands of the man who murdered your two sons. Think of putting your girls in the power of the man who murdered their brothers! They themselves must be unable to bear the sight of him. Better to stay in sanctuary than force them to kiss his hand and live under the command of his wife. I know you will feel this as I do: it is impossible. For your own sake at least, command your girls to stay with you quietly in the country if Richard will release them, or peacefully in sanctuary if he will not, until that Happy Day when Elizabeth shall be queen of her own court and my beloved daughter as well as yours. Your truest friend in all the world, imprisoned just as you are, Lady Margaret Stanley

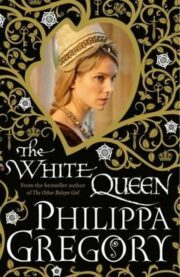

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.