I write back:

Tell him, I am still as good as the word that I gave to his mother, Lady Margaret. Elizabeth will be his wife when he defeats Richard and takes the throne of England. Let York and Lancaster be as one and let the wars be over.

I pause, and add a note.

Ask him if his mother knows what happened to my boy Edward.

DECEMBER 1483

I wait till the turning of the year, the darkest night of the year, and I wait for the darkest hour, the hour between midnight and one, then I take a candle and throw a warm cape over my winter gown and tap on Elizabeth’s door. “I am going now,” I say. “Do you want to come?”

She is ready. She has her candle and her cape with the hood pulled forward over her bright hair. “Yes, of course. This is my loss too,” she says. “I want revenge too. Those who killed my brother have put me a step closer to the throne, a step further away from the life I might have made for myself, and into the heart of danger. I don’t thank them for that, either. And my brother was alone and unguarded, taken away from us. It would have to be someone made of stone to kill our prince and that poor little page boy. Whoever it was has earned a curse. I will curse him.”

“It will be on his son,” I warn her, “and his son after him. It will end their line.”

Her eyes shine green in the candlelight like a cat’s eyes. “So might it be,” she says, as her grandmother Jacquetta would say when she was cursing or blessing.

I lead the way and we go through the silent crypt, down the stone stairs to the catacombs, and then down again, another flight of cold stone stairs, icy damp underfoot, until we hear the lapping of the river at the water gate.

Elizabeth unlocks the iron door and together we pull it open. The river is high, at the level of a winter flood, dark and glassy, moving swiftly by us in the darkness of the night. But it is nothing to the storm that Elizabeth and I called up to keep Buckingham and Henry Tudor out of London. If I had only known that someone was coming for my son that night, I would have taken a boat on that flood and gone to him. I would have gone on the deep waters to save him.

“How shall we do this?” Elizabeth is shivering from the cold and from fear.

“We do nothing,” I say. “We just tell Melusina. She is our ancestor, she is our guide, she will feel the loss of our son and heir as we do. She will seek out those who took him, and she will take their son in return.”

I unfold a piece of paper from my pocket and give it to Elizabeth. “Read it aloud,” I say. I hold the two candles for her as she reads it to the swiftly moving waters.

“Know this, that our son Edward was in the Tower of London held prisoner most wrongly by his uncle Richard, now called king. Know this, that we gave him a companion, a poor boy, to pass for our second son Richard but got him away safe to Flanders, where you guard him on the River Scheldt. Know this, that someone either came and took our son Edward, or killed him where he slept; but, Melusina! we cannot find him, and we have not been given his body. We cannot know his killers, and we cannot bring them to justice nor, if our boy still lives, find him and bring him home to us.” Her voice quavers for a moment and I have to dig my nails into the palms of my hands to stop myself from crying.

“Know this: that there is no justice to be had for the wrong that someone has done to us, so we come to you, our Lady Mother, and we put into your dark depths this curse: that whoever took our firstborn son from us, that you take his firstborn son from him. Our boy was taken when he was not yet a man, not yet king-though he was born to be both. So take his murderer’s son while he is yet a boy, before he is a man, before he comes to his estate. And then take his grandson too, and when you take him, we will know by his death that this is the working of our curse and this is payment for the loss of our son.”

She finishes reading and her eyes are filled with tears. “Fold it like a paper boat,” I say.

Readily she takes the paper and makes a perfect miniature vessel; the girls have been making paper fleets ever since we were first entrapped here beside the river. I hold out the candle. “Light it,” I whisper, and she holds the folded paper boat into the flame of the candle so the prow catches fire. “Send it into the river,” I say, and she takes the flaming boat and puts it gently on the water.

It bobs, the flame flickers as the wind blows it, but then it flares up. The swift current of the water takes it, and it turns and swirls away. For a moment we see it, flame on reflected flame, the curse and the mirror of the curse, paired together on the dark flood, and then they are whirled away by the rush of the river and we are looking into blackness, and Melusina has heard our words and taken our curse into her watery kingdom.

“It’s done,” I say, and turn away from the river and hold the water gate open for her.

“That’s all?” she asks as if she had expected me to sail down the river in a cockleshell.

“That’s all. That’s all I can do, now that I am queen of nothing, with missing sons. All I can do now is ill-wishing. But God knows, I do that.”

CHRISTMAS 1483

I make merry for my girls. I send out Jemma to buy them new brocade and we sew new dresses, and they wear the last diamonds from the royal Treasury on their heads as crowns for Christmas Day. The defeated county of Kent sends us a handsome capon, wine, and bread for our Christmas feast. We are our own carolers, we are our own mummers, we are our own wassailers. When finally I put the girls to bed, they are happy, as if they had forgotten the York court at Christmas when every ambassador said he had never seen a richer court, and their father was King of England and their mother the most beautiful queen the country had ever seen.

Elizabeth my daughter sits late with me before the fire, cracking nuts and throwing the shells into the red embers so they flare and spit.

“Your uncle Thomas Grey writes to me that Henry Tudor was going to declare himself King of England and your betrothed in Rennes Cathedral today. I should congratulate you,” I say.

She turns and gives me her merry smile. “I am a much married woman,” she says. “I was betrothed to Warwick’s nephew, and then to the heir of France, d’you remember? And you and Father called me La Dauphine, and I took extra lessons in French and thought myself very great. I was meant to be Queen of France, I was certain of it, and yet now look at me! So I think I shall wait till Henry Tudor has landed, fought his battle, crowned himself king, and asked me himself before I count myself a betrothed woman.”

“Still, it is time you were married,” I say almost to myself, thinking of her rising blush when her uncle Richard said that she had grown so much he hardly knew her.

“Nothing can happen while we are in here,” she says.

“Henry Tudor is untested.” I am thinking aloud. “He has spent his life running away from our spies, he has never turned and fought. The only battle he ever saw was under the command of his guardian William Herbert, and then he fought for us! When he lands in England with you as his declared bride, then everyone who loves us will turn out for him. Everyone else will turn out for him for hatred of Richard, even though they hardly know Henry. Everyone who has been deprived of their places by the northerners whom Richard brought in will turn out for him. The rebellion has left a sour taste for too many people. Richard won that battle, but he has lost the trust of the people. He promises justice and freedom, but since the rebellion he puts in northern lords and he rules with his friends. Nobody will forgive him that. Your betrothed will have thousands of recruits, and he will come with an army from Brittany. But it will all depend on whether he is as brave in battle as Richard. Richard is battle-hardened. He fought all over England when he was a boy, under the command of your father. Henry is new to the field.”

“If he wins, and if he honors his promise, then I will be Queen of England. I told you I would be Queen of England one day. I always knew it. It is my fate. But it was never my ambition.”

“I know,” I say gently. “But if it is your destiny, you will have to do your duty. You will be a good queen, I know. And I will be there with you.”

“I wanted to marry a man that I loved, as you did Father,” she says. “I wanted to marry a man for love, not a stranger on the word of his mother and mine.”

“You were born a princess, and I was not,” I remind her. “And even so, I had to take my first husband on the say-so of my father. It was only when I was widowed that I could choose for myself. You will have to outlive Henry Tudor and then you can do as you please.”

She giggles and her face lights up at the thought of it.

“Your grandmother married her husband’s young squire the moment she was widowed,” I remind her. “Or think of King Henry’s mother, who married a Tudor nobody in secret. At least when I was a widow I had the sense to fall in love with the King of England.”

She shrugs. “You are ambitious. I am not. You would never fall in love with someone who was not wealthy or great. But I don’t want to be Queen of England. I don’t want my poor brother’s throne. I have seen the price that one pays for a crown. Father never stopped fighting from the day he won it, and here we are-trapped in little better than prison-because you still hope we can gain the throne. You will have the throne even if it means I have to marry a runaway Lancastrian.”

I shake my head. “When Richard sends me his proposals, we will come out,” I say. “I promise you. It is time. You won’t have another Christmas in hiding. I promise you, Elizabeth.”

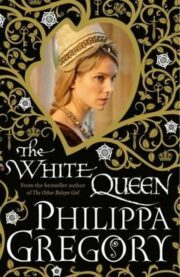

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.