I don’t hesitate. It is as if the thud of axe through Hastings’s neck on Tower Green is a trumpet blast that signals the start of a race. But this is a race to get my son to safety from the threat of his uncle, who is now on a path of murder. There is no doubt in my mind anymore that Duke Richard will kill both my sons to make his way clear to the throne. I would not give a groat for the life of George’s son, either, wherever he is housed. I saw Richard go into the room of the sleeping King Henry to kill a defenseless man because his claim to the throne was as good as Edward’s. There is no doubt in my mind that Richard will follow the same logic as the three brothers did that night. A sacred and ordained king stood between their line and the throne-and they killed him. Now my boy stands between Richard and the throne. He will kill him if he can, and it may be that I cannot prevent it. But I swear, he will not get my younger boy Richard.

I have prepared him for this moment, but when I tell him that he will have to go at once, tonight, he is startled that it has come so soon. His color drains away from his cheeks, but his bright boyish bravery makes him hold his head up and bite his little lip so as not to cry. He is only nine, but he has been raised to be a prince of the House of York. He has been raised to show courage. I kiss him on the top of his fair head and tell him to be a good boy, and remember all that he has been told to do, and when it starts to grow dark, I lead him down through the crypt, down the stairs, even deeper, down into the catacomb below the building, where we have to go past the stone coffins and the vaulted rooms of the burial chambers with one lantern before us and one in his little hand. The light does not flicker. He does not tremble even when we go past the shadowy graves. He walks briskly beside me, his head up.

The way leads out to a hidden iron gate, and beyond it a stone pier extending out into the river, with a rocking rowing boat silently alongside. It is a little wherry, hired for river traffic, one of hundreds. I had hoped to send him out in the warship, commanded by my brother Edward, with men at arms sworn to protect him; but God knows where Edward is this night, and the fleet has turned against us, and will sail for Richard the duke. I have no warships at my command. We will have to make do with this. My boy has to go out with no protection but two loyal servants, and the blessing of his mother. One of Edward’s friends is waiting for him at Greenwich, Sir Edward Brampton, who loved Edward. Or so I hope. I cannot know. I can be certain of nothing.

The two men are waiting silently in the boat, holding it against the current with a rope through the ring on the stone steps, and I push my boy towards them and they lift him on board and seat him in the stern. There is no time for any farewells, and anyway there is nothing I can say but a prayer for his safety that catches me in the throat as if I have swallowed a dagger. The boat pushes off and I raise my hand to wave to him, and see his little white face under the big cap looking back at me.

I lock the iron gate behind me, and then go back up the stone steps, silent through the silent catacombs, and I look out from my window. His boat is pulling away into the river traffic, the two men at the oars, my boy in the stern. There is no reason for anyone to stop them. There are dozens like them, hundreds of boats crisscrossing the river, about their own business, two workingmen with a lad to run errands. I swing open my window but I will not call to him. I will not call him back. I just want him to be able to see me if he glances up. I want him to know that I did not let him go lightly, that I looked for him until the last, the very last moment. I want him to see me looking for him through the dusk, and know that I will look for him for the rest of my life, I will look for him till the hour of my death, I will look for him after death, and the river will whisper his name.

He does not glance up. He does as he was told. He is a good boy, a brave boy. He remembers to keep his head down and his cap pulled down on his forehead to hide his fair hair. He must remember to answer to the name of Peter, and not expect to be served on bended knee. He must forget the pageants and the royal progresses, the lions at the Tower, and the jester tumbling head over heels to make him laugh. He must forget the crowds of people cheering his name and his pretty sisters who played with him and taught him French and Latin and even a little German. He must forget the brother he adored who was born to be king. He must be like a bird, a swallow, who in winter flies beneath the waters of the rivers and freezes into stillness and silence and does not fly out again until spring comes to unlock the waters and let them flow. He must go like a dear little swallow into the river, into the keeping of his ancestress Melusina. He must trust that the river will hide him and keep him safe, for I can no longer do so.

I watch the boat from my window and at first I can see him in the stern, rocking as the little wherry moves in steady pulses, as the boatman pulls on the oars. Then the current catches it and they go faster and there are other boats, barges, fishing boats, trading ships, ferryboats, wherries, even a couple of huge logging rafts, and I can see my boy no longer and he has gone to the river and I have to trust him to Melusina and the water, and I am left without him, marooned without my last son, stranded on the riverbank.

My grown son, Thomas Grey, goes the same night. He slips out of the door dressed like a groom into the backstreets of London. We need someone on the outside to hear news and raise our forces. There are hundreds of men loyal to us, and thousands who would fight against the duke. But they must be mustered and organized, and Thomas has to do this. There is no one else left who can. He is twenty-seven. I know I am sending him out to danger, perhaps to his death. “Godspeed,” I say to him. He kneels to me and I put my hand on his head in blessing. “Where will you go?”

“To the safest place in London,” he says with a rueful smile. “A place that loved your husband and will never forgive Duke Richard for betraying him. The only honest business in London.”

“Where d’you mean?”

“The whorehouse,” he says with a grin.

And then he turns into the darkness and is gone.

Next morning, early, Elizabeth brings the little page boy to me. He served us at Windsor, and has agreed to serve us again. Elizabeth holds him by the hand for she is a kind girl, but he smells of the stables, where he has been sleeping. “You will answer to the name of Richard, Duke of York,” I tell him. “People will call you my lord, and sire. You will not correct them. You will not say a word. Just nod.”

“Yes’m,” he mumbles.

“And you will call me Lady Mother,” I say.

“Yes’m.”

“Yes, Lady Mother.”

“Yes, Lady Mother,” he repeats.

“And you will have a bath and put on clean clothes.”

His frightened little face flashes up at me. “No! I can’t bathe!” he protests.

Elizabeth looks aghast. “Anyone will know at once,” she says.

“We’ll say he is ill,” I say. “We’ll say he has a cold or a sore throat. We’ll tie up his jaw with a flannel and put a scarf around his mouth. We’ll tell him to be silent. It’s only for a few days. Just to give us time.”

She nods. “I’ll bathe him,” she says.

“Get Jemma to help you,” I say. “And one of the men will probably have to hold him in the water.”

She finds a smile, but her eyes are shadowed. “Mother, do you really think my uncle the duke would harm his own nephew?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “And that is why I have sent my beloved royal son away from me, and my boy Thomas Grey has to go out into the darkness. I don’t any longer know what the duke might do.”

The serving girl Jemma asks if she can go out on Sunday afternoon to see the Shore whore serve her penance. “To do what?” I ask.

She dips a curtsey, her head bowed low, but she is so desperate to go that she is ready to risk offending me. “I am sorry, ma’am, Your Grace, but she is to walk in the city in her kirtle carrying a lighted taper and everyone is going to see her. She has to do penance for sin, for being a whore. I thought if I came in early every day for the next week you might let me-”

“Elizabeth Shore?”

Her face bobs up. “The notorious whore,” she recites. “The lord protector has ordered that she do public penance for her sins of the flesh.”

“You can go and watch,” I say abruptly. One more gaze in the crowd will make no difference. I think of this young woman who Edward loved, who Hastings loved, walking barefoot in her petticoat, carrying a taper, shielding its flickering flame while people shout abuse or spit on her. Edward would not like this, and for him, if not for her, I would stop it if I could. But there is nothing I can do to protect her. Richard the duke has turned vicious and even a beautiful woman has to suffer for being beloved.

“She is punished for nothing but her looks.” My brother Lionel has been listening at the window for the appreciative murmur of the crowd as she walks around the city boundary. “And because now Richard suspects her of hiding your brother Thomas. He raided her house but he couldn’t find Thomas. She kept him safe, hidden from Gloucester’s men, and then got him out of the way.”

“God bless her for that,” I say.

Lionel smiles. “Apparently, this punishment has gone wrong for Duke Richard anyway. Nobody is speaking ill of her as she walks,” he says. “One of the ferryboat men shouted up at me when I was at the window. He says that the women cry shame on her, shame, and the men just admire her. It’s not every day that they see such a lovely woman in her petticoat. They say she looks like a naked angel, beautiful and fallen.”

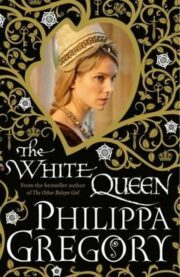

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.