“I am come on the order of Bishop Morton,” he says quietly. “If anyone asks you, I came to offer you a chance to confess, and you spoke to me of a sin of sadness and excessive grief, and I counseled you against despair. Agreed?”

“Yes, Father,” I say.

He passes me a slip of paper. “I shall wait ten minutes and then leave,” he says. “I am not allowed to take a reply.”

He goes to the stool by the door and sits, waiting for the time to pass. I take the note to the window for the light, and as the river gurgles beneath the window I read it. It is sealed with the crest of the Beauforts. It is from Margaret Stanley, my former lady-in-waiting. Despite being Lancaster born and bred, and mother to their heir, she and her husband Thomas Stanley have been loyal to us for the last eleven years. Perhaps she will stay loyal. Perhaps she will even take my side against Duke Richard. Her interests lie with me. She was counting on Edward to forgive her son his Lancaster blood and let him come home from his exile in Brittany. She spoke to me of a mother’s love for her boy and how she would give anything to have him home again. I promised her that it would happen. She has no reason to love Duke Richard. She might well think her chances of getting her boy home are better if she stays friends with me and supports my return to power.

But she has written nothing of a conspiracy nor words of support. She has written only a few lines:

Anne Neville is not journeying to London for the coronation. She has not ordered horses or guards for the journey. She has not been fitted for special robes for the coronation. I thought you would like to know. M S

I hold the letter in my hand. Anne is sickly and her son is weak. She might prefer to stay at home. But Margaret, Lady Stanley, has not gone to all this trouble and danger to tell me this. She wants me to know that Anne Neville is not hastening to London for the grand coronation, for there is no need for her to make haste. If she is not coming, it will be at her husband Richard’s command. He knows that there will be nothing to attend. If Richard has not ordered his wife to London in time for the coronation, the most important event of the new reign, then it must be because he knows that a coronation will not take place.

I stare out at the river for a long, long time and think what this means for me and my two precious royal sons. Then I go and kneel before the friar. “Bless me, Father,” I say, and I feel his gentle hand come down on my head.

The serving maid who goes out to buy the bread and meat every day comes home, her face white, and speaks to my daughter Elizabeth. My girl comes to me.

“Lady Mother, Lady Mother, can I speak with you?”

I am looking out of the window, brooding on the water as if I hope Melusina might rise out of the summertime sluggish flow and advise me. “Of course, sweetheart. What is it?”

Something about her taut urgency warns me.

“I don’t understand what is happening, Mother, but Jemma has come home from the market and says there is some story of a fight in the Privy Council, an arrest. A fight in the council room! And Sir William…” She runs out of breath.

“Sir William Hastings?” I name Edward’s dearest friend, the sworn defender of my son, and my newfound ally.

“Yes, him. Mother, they are saying in the market that he is beheaded.”

I hold the stone windowsill as the room swims. “He can’t be-she must have it wrong.”

“She says that the Duke Richard found a plot against him, and arrested two great men and beheaded Sir William.”

“She must be mistaken. He is one of the greatest men in England. He cannot be beheaded without trial.”

“She says so,” she whispers. “She says that they took him out and took off his head on a piece of lumber on Tower Green, without warning, without trial, without charge.”

My knees give way beneath me and she catches me as I fall. The room goes dark to me, and then I see her again, her headdress knocked aside, her fair hair spilling down, my beautiful daughter looking into my face, and whispering, “Lady Mother, Mama, speak to me. Are you all right?”

“I’m all right,” I say. My throat is dry, and I find I am lying on the floor with her arm supporting me. “I am all right, sweetheart. But I thought I heard you say…I thought you said…I thought you said that Sir William Hastings is beheaded?”

“So Jemma said, Mother. But I didn’t think you even liked him.”

I sit up, my head aching. “Child, this is no longer a question of liking. This lord is your brother’s greatest defender, the only defender who has approached me. He doesn’t like me, but he would lay down his life to put your brother on the throne and keep his word to your father. If he is dead, we have lost our greatest ally.”

She shakes her head in bewilderment. “Could he have done something very wrong? Something that offended the lord protector?”

There is a light tap at the door and we all freeze. A voice calls in French, “C’est moi.”

“It’s a woman, open the door,” I say. For a moment I had been certain it was Richard’s headsman, now come for us, with Hastings’s blood unwiped on the blade of his axe. Elizabeth runs to open the lantern door in the big wooden gate and the whore Elizabeth Shore slips in, a hood over her fair head, a cloak wrapped tight around her rich brocade gown. She curtseys low to me, as I am still huddled on the floor. “You’ve heard then,” she says shortly.

“Hastings is not dead?”

Her eyes are filled with tears but she is succinct. “Yes, he is. That’s why I’ve come. He was accused of treason against Duke Richard.”

Elizabeth my daughter drops to her knees beside me and takes my icy hand in hers.

“Duke Richard accused Sir William of conspiring his death. He said that William had procured a witch to act against him. The duke said that he is out of breath and falling sick and that he is losing his strength. He said he has lost the strength in his sword arm, and he bared his arm in the council chamber and showed it to Sir William from the wrist to his shoulder, and said surely he could see it was withering away. He says he is under an enchantment from his enemies.”

My eyes stay on her pale face. I don’t even glance at the fireplace where the twist of linen from the duke’s napkin was burned, after I tied it around my forearm, and then cursed it, to rob him of breath and strength, to make his sword arm weak as a hunchback’s.

“Who does he name as the witch?”

“You,” she says. I feel Elizabeth flinch.

And then she adds, “And me.”

“The two of us acting in concert?”

“Yes,” she says simply. “That’s why I came to warn you. If he can prove you are a witch, can he break sanctuary, and take you and your children out of here?”

I nod. He can.

And in any case, I remember the battle of Tewkesbury, when my own husband broke sanctuary with no reason or explanation, and dragged wounded men out of the abbey and butchered them in the graveyard and then went into the abbey and killed some more on the altar steps. They had to scrub the chancel floor clean of the blood; they had to resanctify the whole place, it was so fouled with death.

“He can,” I say. “Worse has been done before.”

“I must go,” she says fearfully. “He may be watching me. William would have wanted me to do what I can to keep your children safe, but I can do no more. I should tell you: Lord Stanley did what he could to save William. He warned him that the duke would act against him. He had a dream that they would be gored by a boar with bloody tusks. He warned William. It was just that William didn’t think it would be so fast…” The tears are running down her cheeks now and her voice is choked. “So unjust,” she whispers. “And against such a good man. To have soldiers drag him from council! To take off his head without even a priest! No time to pray!”

“He was a good man,” I concede.

“Now that he is gone you have lost a protector. You are all in grave danger,” she states. “As am I.”

She pulls the hood back over her hair and goes to the door. “I wish you well,” she says. “And Edward’s boys. If I can serve you, I will. But in the meantime I must not be seen coming to you. I dare not come again.”

“Wait,” I say. “Did you say Lord Stanley remains loyal to the young King Edward?”

“Stanley, Bishop Morton, and Archbishop Rotherham are all imprisoned by order of the duke, suspected of working for you and yours. Richard thinks they have been plotting against him. The only men left free in the council now are those who will do the duke’s bidding.”

“Has he run mad?” I ask incredulously. “Has Richard run mad?”

She shakes her head. “I think he has decided to claim the throne,” she says simply. “D’you remember how the king used to say that Richard always did what he promised? That if Richard swore he would do something it was done-cost what it may?”

I don’t like to have this woman quoting my husband to me, but I agree.

“I think Richard has made his decision, I think he has promised to himself. I think he has decided that the best thing for him, and for England, is a strong new king and not a boy of twelve. And now he has made up his mind, he will do whatever it takes to put himself on the throne. Cost what it may.”

She opens the door a crack and peers out. She picks up the basket to make it look as if she was delivering goods to us. She peeps back at me around the door. “The king always said that Richard would stop at nothing once he had agreed a plan,” she says. “If he stops at nothing now, you will not be safe. I hope you can make yourself safe, Your Grace, you and the children…you and Edward’s boys.” She dips a little curtsey and whispers, “God bless you for his sake,” and the door clicks behind her and she has gone.

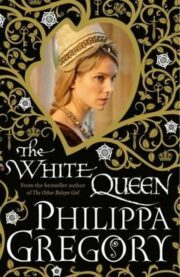

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.