I had been afraid that he would note that I was growing older. But instead he smiles at me as if we were still young lovers, and kisses my hand. “No man could have asked for more,” he says sweetly to me. “And no queen has ever labored harder. You have given me a great family, my love. And I am glad this will be our last.”

“You don’t want another boy?”

He shakes his head. “I want to take you for pleasure, and hold you in my arms for desire. I want you to know that it is your kiss that I want, not another heir to the throne. You can know that I love you, quite for yourself, when I come to your bed, and not as the York’s broodmare.”

I tilt back my head and look at him under my eyelashes. “You think to bed me for love and not for children? Isn’t that sin?”

His arm comes around my waist and his palm cups my breast. “I shall make sure that it feels richly sinful,” he promises me.

APRIL 1483

The weather is cold and unseasonal and the rivers run high. We are at Westminster for the feast of Easter, and I look from my window at the fullness and the fast flow of the river and think of my son Edward, beyond the great waters of the Severn River, far away from me. It is as if England is a country of intersecting waterways, lakes and streams and rivers. Melusina must be everywhere; this is a country made in her element.

My husband Edward, a man of the land, has a whim to go fishing and takes himself out for the day and comes home soaking wet and merry. He insists that we eat the salmon that he caught in the river for our dinner, and it is borne into the dining room at shoulder height with a fanfare: a royal catch.

That night he is feverish and I scold him for getting wet and cold, as if he were still a boy and could take such risks with his health. The next day he is worse and he gets up for a little while but then goes back to bed: he is too tired. The next day the physician says that he should be bled, and Edward swears that they may not touch him. I tell the doctors that it shall be as the king insists, but I go to his room when he is sleeping and I look at his flushed face to reassure myself that this is nothing more than a passing illness. This is not the plague or a serious fever. He is a strong man in good health. He can take a chill and throw it off within a week.

He gets no better. And now he starts to complain of gripping pains in the belly and a terrible flush of heat. Within a week the court is in fear, and I am in a state of silent terror. The doctors are useless: they don’t even know what is wrong with him; they don’t know what has caused his fever; they don’t know what will cure it. He can keep nothing down. He vomits everything he eats, and he is fighting the pain in his belly as if it were a new war. I keep a vigil in his room, my daughter Elizabeth beside me, nursing him with two wise women whom I trust. Hastings, the friend of his boyhood and his partner in every enterprise including the stupid, stupid fishing trip, keeps his vigil in the outer room. The Shore whore has taken to living on her knees at the altar in Westminster Abbey, they tell me, in an agony of fear for the man she loves.

“Let me see him,” William Hastings implores me.

I turn a cold face to him. “No. He is sick. He needs no companion for whoring or drinking or gambling. So he has no need of you. His health has been ruined by you, and all them like you. I will nurse him to health now, and, if I have my way, when he is well he will not see you again.”

“Let me see him,” he says. He does not even defend himself against my anger. “All I want is to see him. I can’t bear not to see him.”

“Wait like a dog out here,” I say cruelly. “Or go back to the Shore whore and tell her that she can service you now, for the king has finished with you both.”

“I’ll wait,” he says. “He will ask for me. He will want to see me. He knows I am here waiting to see him. He knows I am out here.”

I walk past him to the king’s bedchamber, and I close the door so he cannot even glimpse the man he loves, fighting for breath in the big four-poster bed.

Edward looks up when I come in. “Elizabeth.”

I go to him and hold his hand. “Yes, love.”

“You remember I came home to you and told you I had been afraid?”

“I remember.”

“I am afraid again.”

“You will get well,” I whisper urgently. “You will get well, my husband.”

He nods and his eyes close for a moment. “Is Hastings outside?”

“No,” I say.

He smiles. “I want to see him.”

“Not now,” I say. I stroke his head. It is burning hot. I take up a towel and soak it with lavender water and gently bathe his face. “You are not strong enough to see anyone now.”

“Elizabeth, fetch him, and fetch every one of my Privy Council who is in the palace. Send for Richard my brother.”

For a moment I think I have caught his sickness, as my belly turns over with such a pain; then I realize this is fear. “You don’t need to see them, Edward. All you need to do is rest and grow strong.”

“Fetch them,” he says.

I turn and say a sharp word to the nurse, and she runs to the door and tells the guard. At once, the message goes out all through the court that the king has summoned his advisors, and everyone knows that he must be dying. I go to the window and stand with my back to the view of the river. I don’t want to see the water; I don’t want to see the glimmer of a mermaid’s tail; I don’t want to hear Melusina singing to warn of a death. The lords file into the room, Stanley, Norfolk, Hastings, Cardinal Thomas Bourchier, my brothers, my cousins, my brothers-in-law, half a dozen others: all the great men of the kingdom, men who have been with my husband from the days of his earliest challenge, or men like Stanley, who are always perfectly aligned to the winning side. I look at them stony-faced, and they bow to me: grim-faced.

The women have propped Edward up so he can see the council. Hastings’s eyes are filled with tears, his face twisted with pain. Edward reaches out a hand to him, and they grip each other as if Hastings would hold him to life.

“I fear I have not long,” Edward says. His voice is a rasping whisper.

“No,” whispers Hastings. “Don’t say it. No.”

Edward turns his head and speaks to them all. “I leave a young son. I had hoped to see him grow to a man. I had hoped to leave you with a man for king. Instead, I have to trust you to care for my boy.”

I have my fist to my mouth to stop myself from crying out. “No,” I say.

“Hastings,” Edward says.

“Lord.”

“And all of you, and Elizabeth my queen.”

I step to his bedside and he takes my hand in his, joins it with Hastings’s, as if he were making us wed. “You have to work together. All of you have to forget your enmities, your rivalries, your hatreds. You all have scores to settle; you all have wrongs you can’t forget. But you have to forget. You have to be as one to keep my son safe and see him to the throne. I ask you this, I demand this of you, from my deathbed. Will you do it?”

I think of all the years that I have hated Hastings, Edward’s dearest friend and companion, the partner for all his drinking and whoring bouts, the friend at his side in battle. I remember how Sir William Hastings, from the very first moment, despised and looked down on me from his high horse when I stood at the roadside, how he opposed the rise of my family and always and again urged the king to listen to other advisors and employ other friends. I see him look at me and, even though tears are pouring down his face, his eyes are hard. He thinks I stood at the roadside and cast a spell on a young boy for his ruin. He will never understand what happened that day between a young man and a young woman. There was a magic: and the name of it was love.

“I will work with Hastings for my son’s safety,” I say. “I will work with all of you and forget all wrongs, to put my son safely on the throne.”

“I too,” says Hastings, and then they all say, one after another. “And I.”

“And I’

“And I.”

“My brother Richard is to be his guardian,” Edward says. I flinch and would pull my hand away, but Hastings has it in a tight grip. “As you wish, Sire,” he says, looking hard at me. He knows that I resent Richard, and the power of the north that he can command.

“Anthony, my brother,” I say in a whisper, prompting the king.

“No,” Edward says stubbornly. “Richard, Duke of Gloucester, is to be his guardian and Protector of the Realm till Prince Edward takes his throne.”

“No,” I whisper. If I could only get the king alone, I could tell him that, with Anthony as protector, we Riverses could hold the country safe. I don’t want my power threatened by Richard. I want my son surrounded by my family. I don’t want any one of the York affinity in the new government that I will make around my son. I want this to be a Rivers boy on England’s throne.

“Do you so swear?” Edward says.

“I do,” they all say.

Hastings looks at me. “Do you swear?” he asks. “Do you swear that, just as we promise to put your son on the throne, you promise to accept Richard, Duke of Gloucester, as protector?”

Of course I do not. Richard is no friend of mine, and he commands half of England already. Why would I trust him to put my son on the throne, when he is a York prince himself? Why would he not take the chance to seize the throne for himself? And he has a son, a boy by little Anne Neville, a boy who could be Prince of Wales in place of my own prince. Why would Richard, who has fought half a dozen battles for Edward, not fight one more for himself?

Edward’s face is gray with fatigue. “Swear it, Elizabeth,” he whispers. “For my sake. For Edward’s sake.”

“Do you think it will make Edward safe?”

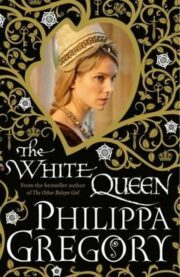

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.