George’s malice to his brother becomes horribly apparent in the days of the trial of Burdett and his conspirators. When they hunt for evidence, the plot unravels to reveal a tangle of dark promises and threats, recipes for poisoned capes, a sachet of ground glass, and outright curses. In Burdett’s papers they find not only a chart of days drawn up to foretell Edward’s death, but a set of spells designed to kill him. When Edward shows them to me, I cannot stop myself shivering. I tremble as if I had an ague. Whether they can cause death or not, I know that these ancient drawings on dark paper have a malevolent power. “They make me cold,” I say. “They feel so cold and damp. They feel evil.”

“Certainly they are evil evidence,” Edward says grimly. “I would not have dreamed that George could have gone so far against me. I would have given the world for him to live at peace with us, or at the very least to keep this quiet. But he hired such incompetent men that now everyone knows that my own brother was conspiring against me. Burdett will be found guilty and he will hang for his crime. But it is bound to come out that George directly commissioned him. George is guilty of treason too. But I cannot put my own brother on trial!”

“Why not?” I ask sharply. I am seated on a low cushioned stool by the fire in my bedroom, wearing only my fur-lined night cape. We are on our way to our separate beds, but Edward cannot keep his trouble to himself any longer. Burdett’s slimy spells may not have hurt his health, but they have darkened his spirit. “Why can you not put George on trial and send him to a traitor’s death? He deserves it.”

“Because I love him,” he says simply. “As much as you do your brother Anthony. I cannot send him to the scaffold. He is my little brother. He has been at my side in battle. He is my kinsman. He is my mother’s favorite. He is our George.”

“He has been on the other side in battle too,” I remind him. “He has been a traitor to you and your family more than once already. He would have seen you dead if he and Warwick had caught you and you had not escaped. He named me as a witch, he had my mother arrested, he stood by and watched as they killed my father and my brother John. He lets neither justice nor family feeling block his way. Why should you?”

Edward, seated in the chair on the other side of the fire, leans forward. His face in the flickering light looks old. For the first time I see the weight of years and kingship on him. “I know. I know. I should be harder on him, but I cannot. He is my mother’s pet; he is our little golden boy. I cannot believe he is so-”

“Vicious,” I give him the word. “Your little pet has become vicious. He is a grown dog now, not a sweet puppy. And he has a bad nature that has been spoiled from birth. You will have to deal with him, Edward, mark my words. When you treat him with kindness, he repays you with plots.”

“Perhaps,” he says, and sighs. “Perhaps he will learn.”

“He will not learn,” I promise. “You will only be safe from him when he is dead. You will have to do it, Edward. You can only choose the when and the where.”

He gets up and stretches and goes to the bed. “Let me see you into your bed, before I go to my own rooms. I shall be glad when the baby is born and we can sleep together again.”

“In a minute,” I reply. I lean forward and look into the embers. I am the heiress to a water goddess, I never see well in flames; but in the gleam of the ashes I can make out George’s petulant face and something behind him, a tall building, dark as a fingerpost-the Tower. It is always a dark building for me, a place of death. I shrug my shoulders. Perhaps it means nothing.

I rise up and go to bed and huddle under the covers, and Edward takes my hands to kiss me good night.

“Why, you’re chilled,” he says in surprise. “I thought the fire was warm enough.”

“I hate that place,” I say at random.

“What place?”

“The Tower of London. I hate it.”

George’s familiar, the traitor Burdett, protests his innocence on the scaffold at Tyburn before a cat-calling crowd and is hanged anyway; but George, learning nothing from the death of his man, rides in a fury from London and marches into the king’s council meeting at Windsor Castle and repeats the speech, shouting it in Edward’s face.

“Never!” I say to Anthony. I am quite scandalized.

“He did! He did!” Anthony is choking with laughter trying to describe the scene to me in my rooms at the castle, my ladies seated in my presence chamber, Anthony and I tucked away in my private rooms for him to tell me the scandalous news. “There is Edward, standing at least seven feet tall from sheer rage. There is the Privy Council looking quite aghast. You should have seen their faces, Thomas Stanley’s mouth open like a fish! Our brother Lionel clutching his cross on his chest in horror. There is George, squaring up to the king and bellowing his script like a mummer. Of course it makes no sense to half of them, who don’t realize George is doing the scaffold speech from memory, like a strolling player. So when he says “I am an old man, a wise man…” they are all utterly confused.”

I give a little shriek of laughter. “Anthony! They were not!”

“I swear to you, we none of us knew what was happening except Edward and George. Then George called him a tyrant!”

My laughter abruptly dies. “In his own council?”

“A tyrant and a murderer.”

“He called him that?”

“Yes. To his face. What was he talking about? The death of Warwick?”

“No,” I say shortly. “Something worse.”

“Edward of Lancaster? The young prince?”

I shake my head. “That was in battle.”

“Not the old king?”

“We never speak of it,” I say. “Ever.”

“Well, George is going to speak of it now. He looks like a man ready to say anything. You know he is claiming that Edward is not even a son of the House of York? That he is a bastard to Blaybourne the archer? So that George is the true heir?”

I nod. “Edward will have to silence him. This cannot go on.”

“Edward will have to silence him at once,” he warns me. “Or George will bring you, and the whole House of York, down. It is as I said. Your house’s emblem should not be the white rose but the old sign of eternity.”

“Eternity?” I repeat, hopeful that he is going to say something reassuring at this most dark time in our days.

“Yes, the snake which eats itself. The sons of York will destroy each other, one brother destroying another, uncles devouring nephews, fathers beheading sons. They are a house which has to have blood, and they will shed their own if they have no other enemy.”

I put my hands over my belly as if to shield the child from hearing such dark predictions. “Don’t, Anthony. Don’t say such things.”

“They are true,” he says grimly. “The House of York will fall whatever you or I do, for they will eat up themselves.”

I go into my darkened bedchamber for the six weeks of my confinement, leaving the matter still unsettled. Edward cannot think what can be done. A disloyal royal brother is no new thing in England, no new thing for this family, but it is a torment for Edward. “Leave it till I come out,” I say to him on the very threshold of my chamber. “Perhaps he will see sense and beg for a pardon. When I come out, we can decide.”

“And you be of good courage.” He glances at the shadowy room behind me, warm with a small fire, blank-walled, for they take down all images that might affect the shape of the baby waiting to be born. He leans forward. “I shall come and visit you,” he whispers.

I smile. Edward always breaks the prohibition that the confinement chamber should be the preserve of women. “Bring me wine and sweetmeats,” I say, naming the forbidden foods.

“Only if you will kiss me sweetly.”

“Edward, for shame!”

“As soon as you come out then.”

He steps back and formally wishes me well before the court. He bows to me, I curtsey to him, and then I step back and they close the door on the smiling courtiers and I am on my own with the nurses in the small suite of rooms, with nothing to do but wait for the new baby to come.

I have a long hard birth and at the end of it the treasure which is a boy. He is a darling little York boy, with scanty fair hair and eyes as blue as a robin’s egg. He is small and light, and when they put him in my arms, I have an instant pang of fear because he seems so tiny.

“He will grow,” says the midwife comfortingly. “Small babies grow fast.”

I smile and touch his miniature hand and see him turn his head and purse his mouth.

I feed him myself for the first ten days, and then we have a big-bodied wet nurse who comes in and gently takes him from me. When I see her seated in the low chair and the steady way she takes him to her breast, I am sure that she will care for him. He is christened George, as we promised his faithless uncle, and I am churched and I come out of my darkened confinement apartment into the bright sunshine of the middle of August to find that in my absence the new whore, Elizabeth Shore, is all but queen of my court. The king has given up drunken bouts and womanizing in the bathhouses of London. He has bought her a house near to the Palace of Whitehall. He dines with her as well as beds her. He enjoys her company and the court knows it.

“She leaves tonight,” I say briskly to Edward when, resplendent in a gown of scarlet embroidered with gold, he comes to my rooms.

“Who?” he asks mildly, taking a glass of wine at my fireside, no husband more innocent. He waves his hand and the servants whisk from the room, knowing well enough that there is trouble brewing.

“The Shore woman,” I say simply. “Did you not think that someone would greet me with the gossip as soon as I came out of confinement? The wonder is that they held their tongues for so long. I barely stepped out of the chapel door before they were stumbling over each other in their haste to tell me. Margaret Beaufort was particularly sympathetic.”

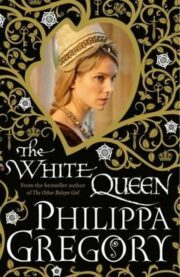

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.