“Impossible,” Edward says. “He is faithless enough when he has a duke’s income paid by me. If he were as rich as a prince with an independent fortune, none of us would be safe. Think of the trouble he would cause for us in Scotland! Dear God, think of him bullying our sister Margaret in Burgundy! She’s only just widowed, her stepdaughter newly orphaned. I would as willingly send a wolf to the two of them as George.”

SPRING 1477

George broods over his brother’s refusal and then we hear outrageous news, news so extraordinary that we start by thinking it must be an exaggerated rumor: it cannot be true. George suddenly declares that Isabel died not of childbed fever, but of poisoning, and bundles the poisoner into jail.

“Never!” I exclaim to Edward. “Has he run mad? Who would have hurt Isabel? Who has he arrested? Why?”

“It is worse than arrest,” he says. He looks quite stunned by the letter in his hand. “He must be crazed. He has rushed this woman servant before a jury and ordered them to find her guilty of murder, and he has had her beheaded. She is dead already. Dead on George’s word, as if there were no law of the land. As if he were a greater power than the law, greater than the king. He is ruling my kingdom as if I had allowed tyranny.”

“Who is she? Who was she?” I demand. “The poor serving girl?”

“Ankarette Twynho,” he says, reading the name from the letter of complaint. “The jury says he threatened them with violence and made them bring in a verdict of guilty, though there was no evidence against her but his oath. They say they did not dare refuse him, and that he forced them to send an innocent woman to her death. He accused her of poison and witchcraft, and of serving a great witch.” He raises his eyes from the letter and sees my white face. “A great witch? Do you know anything of this, Elizabeth?”

“She was my spy in his household,” I confess quickly. “But that is all. I had no need to poison poor little Isabel. What would I gain from it? And witchcraft is nonsense. Why would I cast a spell on her? I didn’t like her, nor her sister, but I wouldn’t ill-wish them.”

He nods. “I know. Of course you didn’t have Isabel poisoned. But did George know that the woman he accused was in your pay?”

“Perhaps. Perhaps. Why else would he accuse her? What else could she have done to offend him? Does he mean to warn me? To threaten us?”

Edward throws down the letter on the table. “God knows! What does he hope to gain by murdering a servant woman but to cause more trouble and gossip? I shall have to act on this, Elizabeth. I can’t let it go.”

“What will you do?”

“He has a little group of his own advisors: dangerous, dissatisfied men. One of them is certainly a practicing fortune-teller, if not worse. I shall arrest them. I shall bring them to trial. I shall do to his men what he has done to your servant. It can serve as a warning for him. He cannot challenge us or our servants without risk to himself. I only hope he has the sense to see it.”

I nod. “They cannot hurt us?” I ask. “These men?”

“Only if you believe, as George seems to think, that they can cast a spell against us.”

I smile in the hope of hiding my fear. Of course I believe that they can cast a spell against us. Of course I fear that they have already done so.

I am right to be troubled. Edward arrests the notorious sorcerer Thomas Burdett, and two others, and they are put to question and a farrago of stories of black arts and threats and enchantments starts to spill out.

My brother Anthony finds me leaning my heavy belly on the river wall and staring into the water at Whitehall Palace on a sunny May afternoon. Behind me, in the gardens, the children are playing a game of bat and ball. By the outraged cries of cheating, I guess that my son Edward is losing and taking advantage of his status as Prince of Wales to change the score. “What are you doing here?” Anthony asks.

“I am wishing this river was a moat that could keep me and mine safe from enemies without.”

“Does Melusina come when you call her from the waters of the Thames?” he asks with a skeptical smile.

“If she did, I would have her hang George, Duke of Clarence, alongside his wizard. And I would have her do that to them both at once, without more words.”

“You don’t believe that the man could hurt you from ill-wishing?” he demands. “He is no wizard. There is no such thing. It is a fairy tale to frighten children, Elizabeth.” He glances back at my children, who are appealing to Elizabeth for a ruling on a dropped catch.

“George believes him. He paid him good money to foretell the king’s death and then some more to bring it about by overlooking. George hired this wizard to destroy us. Already his spells are in the air, in the earth, even in the water.”

“Oh nonsense. He is no more a wizard than you are a witch.”

“I don’t claim to be a witch,” I say quietly. “But I have Melusina’s inheritance. I am her heir. You know what I mean: I have her gift, just as Mother did. Just as my daughter Elizabeth has. The world sings to me and I hear the song. Things come to me; my wishes come true. Dreams speak to me. I see signs and portents. And sometimes I know what will happen in the future. I have the Sight.”

“These could all be revelations from God,” he says firmly. “This is the power of prayer. All the rest is wishful thinking. And women’s nonsense.”

I smile. “I think they are from God. I never doubt it. But God speaks to me through the river.”

“You are a heretic and a pagan,” he says with brotherly scorn. “Melusina is a fairy story, but God and His Son are your avowed faith. For heaven’s sake, you have founded religious houses and chantries and schools in His name. Your love of rivers and streams is a superstition, learned from our mother, like that of ancient pagans. You can’t puddle them up into a religion of your own, and then frighten yourself with devils of your own devising.”

“Of course, brother,” I say with my eyes cast down. “You are a nobleman of learning: I am sure you know best.”

“Stop!” he throws up a hand, laughing. “Stop. You need not think I am going to try to debate with you. You have your own theology, I know. Part fairy tale and part Bible and all nonsense. Please, for all of our sakes, make it a secret religion. Keep it to yourself. And don’t frighten yourself with imaginary enemies.”

“But I do dream true.”

“If you say so.”

“Anthony, my whole life is a proof of magic, that I can foresee.”

“Name one thing.”

“Did I not marry the King of England?”

“Did I not see you stand out in the road like the strumpet you are?”

I exclaim against his crow of laughter. “It was not like that! It was not like that! And besides, my ring came to me from the river!”

He takes my hands and kisses them both. “It is all nonsense,” he says gently. “There is no Melusina but an old, half-forgotten story that Mother used to tell us at bedtime. There is no enchantment but Mother encouraging you with play. You have no powers. There is nothing but what we can do as sinners under the will of God. And Thomas Burdett has no powers but ill-will and a huckster’s promise.”

I smile at him and I don’t argue. But in my heart I know that there is more.

“How did the story of Melusina end?” my little boy Edward asks me that night when I am listening to his bedtime prayers. He is sharing a room with his three-year-old brother Richard, and both boys look at me hopefully, wanting a story to delay their bedtime.

“Why would you ask?” I sit on a chair beside their fire and draw a footstool towards me so I can put up my feet to rest. I can feel the new baby stir in my body. I am six months into my time, and what feels like a lifetime yet to go.

“I heard my lord uncle Anthony speak to you of her today,” Edward says. “What happened after she came out of the water and married the knight?”

“It ends sadly,” I say. I gesture to them that they must get into bed, and they obey me but two pairs of unblinking, bright eyes watch me over their covers. “The stories differ. Some people say that a curious traveler came to their house and spied on her and saw her becoming a fish in her bath. Some say her husband broke his word that she was free to swim alone, and spied on her and saw her become fish again.”

“But why would he mind? Edward asks sensibly. “Since she was half fish when he met her?”

“Ah, he thought he could change her to be the woman he wanted,” I say. “Sometimes a man likes a woman, but then hopes he can change her. Perhaps he was like that.”

“Is there any fighting in this story?” Richard asks sleepily, as his head droops to the pillow.

“No, none,” I say. I kiss Edward’s forehead and then I go to the other bed and kiss Richard. They both still smell like babies, of soap and warm skin. Their hair is soft and smells of fresh air.

“So what happens when he knows she is half fish?” Edward whispers as I go to the door.

“She takes the children and leaves him,” I say. “And they never meet again.”

I blow out a branch of candles but leave the other burning. The firelight in the little grate makes the room warm and cozy.

“That’s really sad,” Edward says mournfully. “Poor man, that he could not see his children or his wife again.”

“It is sad,” I say. “But it is just a story. Perhaps there is another ending that people forgot to tell. Perhaps she forgave him and went back to him. Perhaps he turned into a fish for love and swam after her.”

“Yes.” A happy boy, he is easily comforted. “Good night, Mama.”

“Good night and God bless you both.”

When he saw her, the water lapping on her scales, head down in the bath he had built especially for her, thinking that she would like to wash-not to revert to fish-he had that instant revulsion that some men feel when they understand, perhaps for the first time, that a woman is truly “other.” She is not a boy though she is weak like a boy, nor a fool though he has seen her tremble with feeling like a fool. She is not a villain in her capacity to hold a grudge, nor a saint in her flashes of generosity. She is not any of these male qualities. She is a woman. A thing quite different to a man.What he saw was a half fish, but what frightened him to his soul was the being which was a woman.

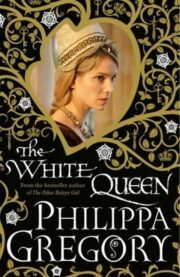

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.