The mare comes and puts her head over the half door to sniff at my shoulder. I stand still, so as not to frighten her. Her warm oaty breath blows on my neck. “You’re very tender of his talents,” I say suspiciously. “Why are you so admiring of him all of a sudden?”

He shrugs his shoulders, and at that small gesture, wifelike, I am on to him. I step forward and take both his hands in mine so he cannot escape my scrutiny. “So who is she?”

“What? What are you talking about?”

“The new one. The new whore. The one who likes Anthony’s poetry,” I say bitingly. “You never read it yourself. You never had such a high opinion of his learning and his destiny before. So someone has been reading to you. My guess is that she has been reading it to you. And if my guess is right, she knows it because he has been reading it to her. And probably Hastings knows her as well, and all of you think she is utterly lovely. But you will be bedding her; and the others sniffing round like dogs. You have a new and agreeable whore, and that I understand. But if you think you are going to share her stupid opinions with me, then she will have to go.”

He looks away from me, at his boots, at the sky, at the new mare.

“What’s her name?” I ask. “You can tell me that, at least.”

He pulls me towards him and folds me in his arms. “Don’t be angry, beloved,” he whispers in my ear. “You know there is only you. Only ever you.”

“Me and a score of others,” I say irritably, but I don’t pull away from him. “They go through your bedroom like a May Day procession.”

“No,” he says. “Truly. There is only you. I have only one wife. I have a score of whores, perhaps hundreds. But only one wife. That is something, is it not?”

“Your whores are young enough to be my daughters,” I say crossly. “And you go out into the city to chase them. And the city merchants complain to me that their wives and their daughters are not safe from you.”

“No,” my husband says with the vanity of a handsome man. “They are not. I hope that no woman can resist me. But I never took anyone by force, Elizabeth. The only woman who ever resisted me was you. D’you remember drawing that dagger on me?”

I smile despite myself. “Of course I do. And you swearing that you would give me the scabbard, but it would be the last thing you ever gave me.”

“There is no one like you.” He kisses my brow and then my closed eyelids and then my lips. “There is no one but you. No one but my wife holds my heart in her beautiful hands.”

“So what is her name?” I ask as he kisses me into peace. “What’s the name of the new whore?”

“Elizabeth Shore,” he says, his lips on my neck. “But that doesn’t matter.”

Anthony comes to my rooms as soon as he arrives at court, having made the journey from Wales, and I greet him at once with an absolute refusal to let him go away.

“No, truly, my dear,” he says. “You have to let me go. I am not going to Jerusalem, not this year, but I want to travel to Rome and confess my sins. I want to be away from the court for a while and think of things that matter and not things that are of the everyday. I want to ride from monastery to monastery and rise at dawn to pray and, where there is no religious house for me to spend the night, I want to sleep under the stars and seek God in the silence.”

“Won’t you miss me?” I ask, childlike. “Won’t you miss Baby? And the girls?”

“Yes, and that’s why I don’t even consider a crusade. I can’t bear to be away for months. But Edward is settled in Ludlow with his playmates and his tutors, and young Richard Grey is a fine companion and model for him. It is safe to leave him for a little while. I have a longing to travel the deserted roads, and I have to follow it.”

“You are a son of Melusina,” I say, trying to smile. “You sound like her when she had to be free to go into the water.”

“It’s like that,” he agrees. “Think of me as swimming away and then the tide will bring me back.”

“Your mind is made up?”

He nods. “I have to have silence to hear the voice of God,” he says. “And silence to write my poetry. And silence to be myself.”

“But you will come back?”

“Within a few months,” he promises.

I stretch out my hands to him, and he kisses them both. “You must come back,” I say.

“I will,” he says. “I have given my word that only death will take me from you and yours.”

JULY 1476

He is as good as his word and returns from his trip to Rome in time to meet us at Fotheringhay in July. Richard has planned and organized a solemn reburial of his father and his brother Edmund, who were killed in battle, made mock of, and hardly buried at all. The House of York rallies together for the funeral and the memorial service, and I am glad Anthony comes home in time to bring Prince Edward to honor his grandfather.

Anthony is as brown as a Moor and full of stories. We steal away together to walk in the gardens of Fotheringhay. He was robbed on the road; he thought he would never get away with his life. He stayed one night beside a spring in a forest and could not sleep for the certainty that Melusina would rise out of the waters. “And what would I say to her?” he demands plaintively. “How confusing for us all if I fell in love with my great-grandmother.”

He met the Holy Father, he fasted for a week and saw a vision, and now he is determined one day to set out again, but this time go farther afield. He wants to lead a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

“When Edward is a man and comes to his own estate, when he is sixteen, I will go,” he says.

I smile. “All right,” I agree easily. “That’s years and years away. Ten years from now.”

“It seems a long time now,” Anthony warns me. “But the years will go quickly.”

“Is this the wisdom of the traveling pilgrim?” I laugh at him.

“It is,” he agrees. “Before you know it, he will be a young man standing taller than you, and we will have to consider what sort of a king we have made. He will be Edward V and he will inherit a throne peacefully, please God, and continue the royal House of York without challenge.”

For no reason at all, I shiver.

“What is it?”

“Nothing, I don’t know. A shiver of cold: nothing. I know he will make a wonderful king. He’s a real York and a real son of the House of Rivers. There could be no better start for a boy.”

DECEMBER 1476

Christmas comes, and my darling son Prince Edward comes home to Westminster for the feast. Everyone marvels at how he has grown. He is seven next year, and a straight-standing, handsome, fair-headed boy with a quickness of understanding and an education that is all from Anthony, and the promise of good looks and charm that is all his father’s.

Anthony brings both my sons to me, Richard Grey and Prince Edward, for my blessing and then releases them to find their brothers and sisters.

“I miss you all three. So much,” I say.

“And I you,” he says, smiling at me. “But you look well, Elizabeth.”

I make a face. “For a woman who is sick every morning.”

He is delighted. “You are expecting a baby again?”

“Again, and given the sickness, they all think it will be a boy.”

“Edward must be delighted.”

“I assume so. He shows his delight by flirting with every woman within a hundred miles.”

Anthony laughs. “That’s Edward.”

My brother is happy. I can tell at once, from the easy set of his shoulders and the relaxed lines around his eyes. “And what about you? Do you still like Ludlow?”

“Young Edward and Richard and I have things just as we want them,” he says. “We are a court devoted to scholarship, chivalry, jousting, and hunting. It is a perfect life for all three of us.”

“He studies?”

“As I report to you. He is a clever boy and a thoughtful one.”

“And you don’t let him take risks hunting?”

He grins at me. “Of course I do! Did you want me to raise a coward for Edward’s throne? He has to test his courage in the hunting field and in the jousting arena. He has to know fear and look it in the face and ride towards it. He has to be a brave king, not a fearful one. I would serve you both very ill if I steered him away from any risk and taught him to fear danger.”

“I know, I know,” I say. “It is just that he is so precious-”

“We are all precious,” Anthony declares. “And we all have to live a life with risk. I am teaching him to ride any horse in the stable and to face a fight without a tremble. That will keep him safer than trying to keep him on safe horses and away from the jousting arena. Now, to far more important things. What have you got me for Christmas? And are you going to name your baby for me, if you have a boy?”

The court prepares for the Christmas feast with its usual extravagance, and Edward orders new clothes for all the children and ourselves as part of the pageant that the world expects from England’s handsome royal family. I spend some time every day with the little Prince Edward. I love to sit beside him when he sleeps, and listen to his prayers as he goes to bed, and summon him to my rooms for breakfast every day. He is a serious little boy, thoughtful, and he offers to read to me in Latin, Greek, or French until I have to confess that his learning far surpasses my own.

He is patient with his little brother Richard, who idolizes him, following him everywhere at a determined trot, and he is tender to baby Anne, hanging over her cradle and marveling at her little hands. Every day we compose a play or a masque, every day we go hunting, every day we have a great ceremonial dinner and dancing and an entertainment. People say that the Yorks have an enchanted court, an enchanted life, and I cannot deny it.

There is only one thing that casts a shadow on the days before Christmas: George the Duke of Dissatisfaction.

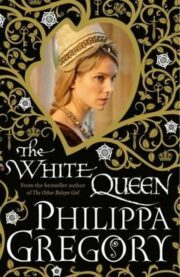

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.