I pull Edward’s face towards me again and I kiss his mouth. “Thank you,” I say. He is leaving my son in my keeping when most kings would say that the boy has to live only with men, taken away from the counsels of women. But Edward makes me the guardian of my son, honors my love for him, respects my judgment. I can bear the separation from Baby if I am to appoint his council, for it means that I shall visit him often and his life shall still be in my keeping.

“And he can come home for feast days and holy days,” Edward says. “I shall miss him too, you know. But he has to be in his principality. He has to make a start at ruling. Wales has to know their prince, and learn to love him. He has to know his land as from childhood, and thus we keep their loyalty.”

“I know,” I say. “I know.”

“And Wales has always been loyal to the Tudors,” Edward adds, almost as an aside. “And I want them to forget him.”

I consider carefully who shall have the raising of my boy in Wales, and who shall head his council and rule Wales for him until he is of age, and then I come to the decision I would have made if I had picked the first name that came to mind, without thinking. Of course. Who else would I trust with the most precious possession in the world?

I go to my brother Anthony’s rooms, which are set back from the main stair, overlooking the private gardens. His door is guarded by his manservant, who swings it open and announces me in a respectful whisper. I cross through his presence chamber and knock on the door of his private room, and enter.

He is seated at a table before the fire, a glass of wine in his hand, a dozen well-sharpened quills before him, sheets of expensive paper covered with crossed-through lines. He is writing, as he does most afternoons when the early darkness of winter drives everyone indoors. He writes every day now, and he no longer posts his poems in the joust: they are too important to him.

He smiles and sets a chair for me close to the fire. He puts a footstool under my feet without comment. He will have guessed that I am with child. Anthony has the eyes of a poet as well as the words. He doesn’t miss much.

“I am honored,” he says with a smile. “Do you have a command for me, Your Grace, or is this a private visit?”

“It is a request,” I say. “Because Edward is going to send Baby to Wales to set up his court, and I want you to go with him as his chief advisor.”

“Won’t Edward send Hastings?” he asks.

“No, I am to appoint Baby’s council. Anthony, there is much profit to be won from Wales. It needs a strong hand, and I would want it to be under our family’s command. It can’t be Hastings, or Richard. I don’t like Hastings, and I never will, and Richard has the Neville lands in the north-we can’t let him have the west too.”

Anthony shrugs. “We have enough wealth and influence, don’t we?”

“You can never have too much.” I state the obvious. “And anyway, the most important thing is that I want you to have the guardianship of Baby.”

“You’d better stop calling him Baby if he is to be Prince of Wales with his own court,” my brother reminds me. “He will be moving to a man’s estate, his own command, his own court, his own country. Soon you will be seeking a princess for him to marry.”

I smile into the warm flames. “I know, I know. We are considering it already. I can’t believe it. I call him Baby because I like to remember how he was when he was in his gowns, but he has his short clothes and he has his own pony now, and is growing every day. I change his riding boots every quarter.”

“He’s a fine little boy,” Anthony says. “And though he takes after his father I sometimes think I see his grandfather in him. You can see he is a Woodville, one of ours.”

“I won’t have anyone but you be his guardian,” I say. “He must be raised as a Rivers at a Rivers court. Hastings is a brute, and I wouldn’t trust the care of my cat to either of Edward’s brothers: George thinks of nothing but himself, and Richard is too young. I want my Prince Edward to learn from you, Anthony. You wouldn’t want anyone else to influence him, would you?”

He shakes his head. “I wouldn’t have him raised by any of them. I didn’t realize the king was setting him up in Wales so soon.”

“This spring,” I say. “I don’t know how I shall bear to let him go.”

Anthony pauses. “I won’t be able to take my wife with me,” he says. “If you thought she might be the Lady of Ludlow. She is not strong enough, and this year she is worse than ever, weaker.”

“I know. If she wants to live at court, I will see she is well cared for. But you would not stay behind for her?”

He shakes his head. “God bless her, no.”

“So you will go?”

“I will, and you can visit us,” Anthony says grandly. “At our new court. Where will we be? Ludlow?”

I nod. “You can learn Welsh and become a bard,” I say.

“Well, I can promise to bring up the boy as you and our family would wish,” he says. “I can keep him to his learning and to his sports. I can teach him what he will need to be a good king of York. And it is something, to raise a king. It is a legacy to leave: that of making the boy who will be king.”

“Enough to sacrifice your pilgrimage for another year?” I ask.

“You know I can never refuse you. And your word is the king’s command and nobody can refuse that. But in truth, I would not refuse to serve the young Prince Edward: it will be something to be guardian of such a boy. I should be proud to have the making of the next King of England. And I will be glad to be at the court of the Prince of Wales.”

“Do I always have to call him that now? Is he not to be Baby anymore?”

“You do.”

SPRING 1473

The young Edward, Prince of Wales and his uncle Earl Rivers, my Grey son Richard, now Sir Richard by order of his stepfather the king, and I make a grand progress to Wales so the little prince can see his country and be seen by as many people as possible. His father says that this is how we make our rule secure: we show ourselves to the people, and by demonstrating our wealth, our fertility, and our elegance we make them feel secure in their monarchy.

We go by slow stages. Edward is strong, but he is not yet three years old and riding all day is too tiring for him. I order that he shall have a rest every afternoon, and go to bed in my chamber, early at night. I am glad of the leisurely pace on my own account, riding pillion so that I can sit sideways as the new curve of my belly is starting to show. We reach the pretty town of Ludlow without incident, and I decide to stay in Wales with my firstborn son for the first half year, until I am certain that the household is organized for his comfort and safety, and that he is settled and happy in his new home.

He is all delight; there is no regret for him. He misses the company of his sisters, but he loves being the little prince at his own court, and he enjoys the company of his half brother, Richard, and his uncle. He starts to learn the land around the castle, the deep valleys and beautiful mountains. He has the servants who have been with him since babyhood. He has new friends in the children of his court, who are brought to learn and play with him, and he has the watchful care of my brother. It is I who cannot sleep for the week before I am due to leave him. Anthony is at ease, Richard is happy, and Baby is joyous in his new home.

Of course, it is almost unbearable for me to leave him, for we have not been an ordinary royal family. We have not had a life of formality and distance. This boy was born in sanctuary under threat of death. He slept in my bed for the first few months of his life-unheard of for a royal prince. He had no wet nurse; I suckled him myself, and it was my fingers that his little hands gripped as he first learned to walk. Neither he, nor any of the others, were sent away to be raised by nurses or in a royal nursery at another palace. Edward has kept his children close, and this, his oldest son, is the first to leave us to take up his royal duties. I love him with a passion: he is my golden boy, the boy who came at last to secure my position as queen and to give his father, then nothing more than a York pretender, a stronger claim to the throne. He is my prince, he is the crown of our marriage, he is our future.

Edward comes to join me for my last month at Ludlow in June, bringing the news that Anthony’s wife, Lady Elizabeth, has died. She had been in ill health for years with a wasting sickness. Anthony orders Masses said for her soul, and I, secretly and ashamed of myself, start to wonder who might be the next wife for my brother.

“Time enough for that,” Edward says. “But Anthony will have to play his part for the safety of the kingdom. He might have to marry a French princess. I need allies.”

“But not go from home,” I say. “And not leave Edward?”

“No. I see he has made Ludlow his own. And Edward will need him here when we leave. And we must leave soon. I have given orders that we will go within the month.”

I gasp, though in truth I have known that this day must come.

“We will come again to see him,” he promises me. “And he will come to us. No need to look so tragic, my love. He is starting his work as a prince of the House of York: this is his future. You must be glad for him.”

“I am glad,” I say, without any conviction at all.

When it is time for me to go, I have to pinch my cheeks to bring color into them, and bite my mouth to stop myself crying. Anthony knows what it costs me to leave the three of them, but Baby is happy, confident that he will come to court in London soon on a visit, enjoying his new freedom and the importance of being the prince in his own country. He lets me kiss him, and hold him without wriggling. He even whispers in my ear, “I love you, Mama,” then he kneels for my blessing; but he comes up smiling.

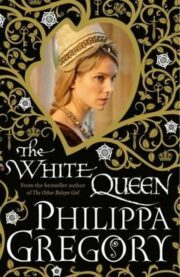

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.