At dusk, on the last day of April, I hear a calling noise, like a white-winged barn owl, and I go to my window and push open the shutters and look out. There is a waning moon rising off the horizon, white against a white sky; it too is wasting away, and in its cold light I can hear a calling, like a choir, and I know it is not the music of owls, nor singers nor nightingales, but Melusina. Our ancestor goddess is calling around the roof of the house, for her daughter Jacquetta of the House of Burgundy is dying.

I stand and listen to the eerie whistling for a while and then I swing the shutters closed and go to my mother’s room. I don’t hurry. I know there is no need to hurry to her anymore. The new baby is in her arms as she lies in her bed, the little head pressed to my mother’s cheek. They are both pale as marble, they are both lying with their eyes shut, they both seem to be peacefully asleep as the shadows of the evening darken the room. The moonlight on the water outside the chamber window throws the reflection of ripples onto the whitewashed ceiling of the room, so they look as if they are underwater, floating with Melusina in the fountain. But I know that they are both gone from me, and our water mother is singing them on their journey down the sweet river to the deep springs of home.

SUMMER 1472

The pain of my mother’s death is not closed for me by her funeral; it is not healed with the months that go slowly by. Every morning, I wake and miss her, as much as the first morning. Every day I have to remember that I cannot ask her opinion, or quarrel with her advice, or laugh at her sarcasm, or look for the guidance of her magic. And every day I find I blame George, Duke of Clarence, even more for the murder of my father and my brother. I believe it was at the news of their deaths at his hand, under the orders of Warwick, that my mother’s loving heart broke, and if they had not been traitorously killed by him, then she too would be alive today.

It is summer, a time for thoughtless pleasure, but I take my sorrow with me, through the picnics and days as we travel through the countryside, on the long rides and nights under a harvest moon. Edward makes my son Thomas the Earl of Huntingdon, and it does not cheer me. I don’t speak of my sadness to anyone but Anthony, who has lost his mother too. And we hardly ever speak of her. It is as if we cannot bring ourselves to speak of her as dead, and we cannot lie to ourselves that she is still alive. But I blame George, Duke of Clarence, for her heartbreak and her death.

“I hate George of Clarence more than ever,” I say to Anthony as we ride down the road to Kent together, a banquet ahead of us and a week spent traveling in the green lanes between the apple orchards. My heart should be light as the court is happy. But my sense of loss comes with me like a hawk on my wrist.

“Because you’re jealous,” my brother Anthony says provocatively, one hand holding the reins of his horse, the other leading my young son, Prince Edward, on his little pony. “You are jealous of anyone Edward loves. You are jealous of me, you are jealous of William Hastings, you are jealous of anyone who entertains the king, and takes him out whoring, and brings him home drunk and amuses him.”

I shrug my shoulders, indifferent to Anthony’s teasing. I have long known that the king’s pleasure in deep drinking with his friends and visiting other women is part of his nature. I have come to tolerate it, especially as it never takes him far from my bed, and when we are there together it is as if we were married in secret that very morning. He has been a soldier on campaign, far from home, with a hundred doxies at his command; he has been an exile in cities where women have hurried to comfort him, and now he is the King of England and every woman in London would be glad to have him-I truly believe that half of them have had him. He is the king. I never thought I was marrying an ordinary man, with moderate appetites. I never expected a marriage where he would sit quietly at my feet. He is the king: he is bound to go his own way.

“No, you are wrong. Edward’s whoring doesn’t trouble me. He is the king, he can take his pleasures where he wants. And I am the queen, and he will always come home to me. Everyone knows that.”

Anthony nods, conceding the point. “But I don’t see why you concentrate your hatred on George. The king’s entire family are as bad as each other. His mother has loathed you and all of us since we first emerged at Reading, and Richard is more awkward and surly every day. Peace doesn’t suit him, for sure.”

“Nothing about us suits him,” I say. “He is as unlike his two brothers as chalk to cheese: small and dark, and so anxious about his health and his position and his soul, always hoping for a fortune and saying a prayer.”

“Edward lives as if there is no tomorrow, Richard as if he wants no tomorrow, and George as though someone should give it to him for free.”

I laugh. “Well, I would like Richard better if he was as bad as the rest of you,” I remark. “And since he has been married, he is even more righteous. He has always looked down on us Riverses; now he looks down on George too. It is that pompous saintliness that I cannot stomach. He looks at me sometimes as if I were some kind of…”

“Some kind of what?”

“Some kind of fat fishwife.”

“Well,” my brother says. “To be honest, you’re getting no younger, and in certain lights, y’know…”

I tap him on the knee with my riding crop, and he laughs and winks at Baby Edward on his little pony.

“I don’t like how he has taken all the north into his keeping. Edward has made him overly great. He has made him a prince in his own principality. It is a danger to us, and to our heirs. It is to divide the kingdom.”

“He had to reward him with something. Richard has laid down his life on Edward’s gambles over and over again. Richard won the kingdom for Edward: he should have his share.”

“But it makes Richard all but a king in his own domain,” I protest. “It gives him the kingdom of the north.”

“Nobody doubts his loyalty but you.”

“He is loyal to Edward, and to his house, but he doesn’t like me or mine. He envies me everything I have, and he doesn’t admire my court. And what does that mean when he thinks of our children? Will he be loyal to my boy, because he is Edward’s boy too?”

Anthony shrugs. “We are raised up, you know. You have brought us up very high. There are a lot of people who think we ride higher than our deserts, and on nothing more than your roadside charms.”

“I don’t like how Richard married Anne Neville.”

Anthony laughs shortly. “Oh sister, nobody liked to see Richard, the wealthiest young man in England, marry the richest young woman in England, but I never thought to see you take the side of George, Duke of Clarence!”

I laugh unwillingly. George’s outrage at having his heiress sister-in-law snatched from his own house by his own brother has entertained us all for half the year.

“Anyway, it is your husband who has obliged Richard,” Anthony remarks. “If Richard wanted to marry Anne for love, he could have done so, and been rewarded by her love. But it took the king to declare her mother’s fortune should be divided between the two girls. It took your honorable husband to declare the mother legally dead-though I believe the old lady stoutly protests her continuing life, and demands the right to plead for her own lands-and it was your husband who took all the fortune from the poor old lady to give to her two daughters, and thus, and so conveniently, to his brothers.”

“I told him not to,” I say irritably. “But he paid no attention to me on this. He always favors his brothers, and Richard far above George.”

“He is right to prefer Richard, but he should not break his own laws in his own kingdom,” Anthony says with sudden seriousness. “That’s no way to rule. It is unlawful to rob a widow, and he has done just that. And she is the widow of his enemy and in sanctuary in a nunnery. He should be gracious to her, he should be merciful. If he were a truly chivalrous knight, he would encourage her to come out of the nunnery and take up her lands, protect her daughters, and curb the greed of his brothers.”

“The law is what powerful men say it shall be,” I say irritably. “And sanctuary is not unbreakable. If you were not a dreamer, far away in Camelot, you would know that by now. You were at Tewkesbury, weren’t you? Did you see the sanctity of holy ground then when they dragged the lords from the abbey and stabbed them in the churchyard? Did you defend sanctuary then? For I heard everyone unsheathed their swords and cut down the men who were coming with their sword hilts held out?”

Anthony shakes his head. “I am a dreamer,” he concedes. “I don’t deny it, but I have seen enough to know the world. Perhaps my dream is of a better one. This York reign is sometimes too much for me, you know, Elizabeth. I cannot bear what Edward does when I see him favor one man and disregard another, and for no reason but that it makes himself stronger or his reign more secure. And you have made the throne your fief: you distribute favors and wealth to your favorites, not to the deserving. And the two of you make enemies. People say that we care for nothing but our own success. When I see what we do, now that we are in power, I sometimes regret fighting under the white rose. I sometimes think that Lancaster would have done just as well, or at any rate no worse.”

“Then you forget Margaret of Anjou and her mad husband,” I say coldly. “My mother herself said to me on the day we rode out for Reading that I could not do worse than Margaret of Anjou and I have not done so.”

He concedes the point. “All right. You and your husband are no worse than a madman and a harpy. Very good.”

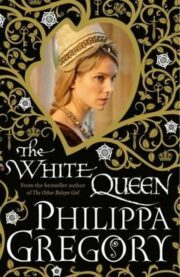

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.