MAY 21, 1471

Edward rides in at the head of his men, looking like a king coming home in glory, no trace of battle in his bearing, on his horse, or on his gleaming harness. Richard is one side of him, George the other, my sons, thrilled, behind them. The York boys are come to their own again, the three of them as one, and London goes mad with joy to see them. Three dukes, six earls, and sixteen barons ride in with them, all of them heartfelt Yorkists and sworn to be faithful. Who would have thought that we had so many friends? Not me, when I was in a sanctuary that was more like a prison, bearing the child that is heir to this glory in darkness and fear and all but alone.

Behind their train comes Margaret of Anjou, white-faced and grim, seated on a litter drawn by mules. They don’t exactly bind her hands and feet and put a silver chain around her throat but I think everyone understands well enough that this woman is defeated and will not rise from her defeat. I take Elizabeth with me when I greet Edward at the gate of the Tower because I want my little daughter to see this woman who has been a terror to her for all her five years, to see her defeated and to know that we are all safe from the one she calls the bad queen.

Edward greets me formally before the cheering crowd but whispers in my ear, “I can’t wait to get you alone.”

But he has to wait. He has knighted half the city of London in thanks for their fidelity, and there is a banquet to celebrate their rise to greatness. In truth, we all have much to be thankful for. Edward has fought for his crown again, and won again, and I am still the wife of a king who has never been beaten in battle. I put my mouth to his ear and whisper back, “I can’t wait either, husband.”

We go to bed late, in his chambers, and half the guests are drunk and the others beside themselves with happiness to find themselves at a York court again. Edward pulls me down beside him and takes me as if we were newly married in the little hunting lodge by the river, and I hold him again, as the man who saved me from poverty and the man who saved England from constant warfare, and I am glad that he calls me “Wife, my darling wife.”

He says against my hair. “You held me when I was afraid, my love. I thank you for that. It’s the first time I have had to go out knowing that I might lose. It made me sick with fear.”

“I saw a battle. Not even a battle, a massacre,” I say, my forehead against his chest. “It’s a terrible thing, Edward. I didn’t know.”

He lies back, his face grim. “It is a terrible thing,” he says. “And there is no one who loves peace more than a soldier. I will bring this country to peace and to loyalty to us. I swear it. Whatever I have to do to bring it about. We have to stop these endless battles. We have to bring this war to an end.”

“It’s vile,” I say. “There is no honor in it at all.”

“It has to end,” he says. “I have to end it.”

We are both silent, and I expect him to sleep, but instead he lies thoughtful, his arms folded behind his head, staring at the golden tester over the bed, and when I say, “What is it, Edward? Is something troubling you?”

He says slowly, “No, but there is something I have to do before I can sleep at peace tonight.”

“Shall I come with you?”

“No, love, this is men’s work.”

“What is it?”

“Nothing. Nothing for you to worry about. Nothing. Go to sleep. I will come back to you later.”

I am alarmed now. I sit up in bed. “What is it, Edward? You look-I don’t know-what is the matter? Are you ill?”

He gets out of bed with sudden decision and pulls on his clothes. “Peace, beloved. I have to go and do something, and when it is done I shall be able to rest. I shall be back within the hour. Go to sleep and I will wake you and have you again.”

I laugh at that, and lie back, but when he is dressed and gone quietly from the room, I slip from the bed and pull on my nightgown. On my bare feet, making no noise, I tiptoe through the privy chamber and out into the presence chamber. The guards are silent at the door, and I nod at them without a word, and they lift their halberds and let me pass. I pause at the head of the stairs and look down. The stair rails curl round and round inside the well of the building, and I can see Edward’s hand going down and down to the floor below us, where the old king has his rooms. I see Richard’s dark head far below me, at the old king’s doorway, as if he is waiting to enter; and I hear George’s voice floating up the stairwell. “We thought you had changed your mind!”

“No. It has to be done.”

I know then what they are about, the three golden brothers of York who won their first battle under three suns in the sky, who are so blessed by God that they never lose. But I do not call out to stop them. I do not run downstairs and catch Edward’s arm and swear that he shall not do this thing. I know that he is of two minds; but I do not throw my opinion on the side of compassion, of living with an enemy, of trusting to God for our safety. I do not think: if they do this, what might someone do to us? I see the key in Edward’s hand, I hear the turning of the lock, I hear the door open to the king’s rooms, and I let the three of them go in, without a word from me.

Henry, madman or saint, is a consecrated king: his body is sacred. He is in the heart of his own kingdom, his own city, his own tower: he must be safe here. He is guarded by good men. He is a prisoner of honor to the House of York. He should be as secure as if he were in his own court: he trusts to us for his safekeeping.

He is one frail man to three young warriors. How can they not be merciful? He is their cousin, their kinsman, and they all three once swore to love and be faithful to him. He is sleeping like a child when the three come into the room. What will happen to us all if they can bring themselves to murder a man as innocent and helpless as a sleeping boy?

I know this is why I have always hated the Tower. I know this is why the tall dark palace on the edge of the Thames has always filled me with foreboding. This death has been on my conscience before we even did it. How heavily it will sit with me from now on only God and my conscience knows. And what price will I have to pay for my part in it, for my silent listening, without a word of protest?

I don’t go back to Edward’s bed. I don’t want to be in his bed when he comes back to me with the smell of death on his hands. I don’t want to be here, in the Tower at all. I don’t want my son to sleep here, in the Tower of London, supposedly the safest place in England, where armed men can walk into the room of an innocent and hold a pillow over his face. I go to my own rooms and I stir up the fire and I sit beside the warmth all night long, and I know without doubt that the House of York has taken a step on a road that will lead us to hell.

SUMMER 1471

I am seated with my mother on a raised bed of camomile, the warm scent of the herb all around us, in the garden of the royal manor of Wimbledon, one of my dower houses, given to me as queen, and still one of my favorite country houses. I am picking out colors for her embroidery. The children are down at the river, feeding ducks with their nursemaid. I can hear their high voices in the distance, calling the ducks by the names they have given them, and scolding them when they don’t respond. Now and then I can hear the distinctive squeak of joy from my son. Every time I hear his voice my heart lifts that I have a boy, and a prince, and that he is a happy baby; and my mother, thinking the same, gives a little nod of satisfaction.

The country is so settled and peaceful, one would think there had never been a rival king and armies marching at double time to face each other. The country has welcomed the return of my husband; we have all rushed towards peace. More than anything else, we all want to get on with our lives under a fair rule, and forget the loss and pain of the last sixteen years. Oh, there are a few who hold out: Margaret Beaufort’s son, now the most unlikely heir to the Lancaster line, is holed up in Pembroke Castle in Wales with his uncle, Jasper Tudor, but they cannot last for long. The world has changed, and they will have to sue for peace. Margaret Beaufort’s own husband, Henry Stafford, is a Yorkist now and fought on our side at Barnet. Perhaps only she, stubborn as a martyr, and her silly son are the last Lancastrians left in the world.

I have a dozen shades of green laid out on my white-gowned knee, and my mother is threading her needle, holding it up to the sky to see better, bringing it closer to her eyes and then farther away again. I think it is the first time in my life I have ever seen a trace of weakness in her. “Can’t you see to thread your needle?” I ask her, half amused.

And she turns and smiles at me and says, quite easily, “My eyes are not the only things that are failing me, and my thread is not the only thing that is blurred. I shan’t see sixty, my child. You should prepare yourself.”

It is as if the day has suddenly gone cold and dark. “Shan’t see sixty!” I exclaim. “Why ever not? Are you ill? You said nothing! Shall you see the physician? We must go back to London?”

She shakes her head and sighs. “No, there is nothing for a physician to see, and thank God, nothing that some fool with a knife would think he could cut out. It is my heart, Elizabeth. I can hear it. It is beating wrongly-I can hear it skip a beat, and then go slowly. It will not beat strongly again, I don’t think. I don’t expect to see many more summers.”

I am so aghast I don’t even feel sorrow. “But what shall I do?” I demand, my hand on my belly, where another new life is beginning. “Mother, what shall I do? You can’t think of it! How shall I manage?”

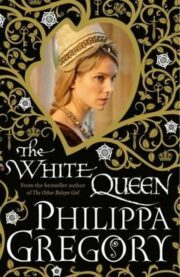

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.