As soon as the shock of the impact throws the York troops back, the flank commanded by Richard comes in at the side and starts to hack and stab, a merciless butchery with the young duke at the very heart of the battle, small, vicious, a killer in the field, an apprentice of terror. The determined push of Richard’s men breaks the onward charge of the Lancastrians and they check. As always in the hand-to-hand fighting there is a lull as even the strongest men catch their breath; but in this pause theYorks push forward, headed by the king with Richard at his side, and start to press the Lancastrians back up the hill to their refuge.

There is a yell, a cold terrifying yell of determined men from the wood to the left of the battle, where no one knew that soldiers were hiding. And two hundred, though it looks like two thousand, spearmen, deadly armed but lightly footed, come running rapidly towards the Lancastrians, the greatest knight in England, Anthony Woodville, far ahead in the lead. Their spears are stretched out before them, hungry for a strike, and the Lancastrian soldiers look up from their slugging battle and see them let fly, like a man might see a storm of lightning bolts: death coming too fast to avoid.

They run, they can bear to do nothing else. The spears come at them like two hundred blades on a single lethal weapon. They can hear the howl of them through the air before the screams as they reach their targets. The soldiers thrash themselves to run back up the hill, and Richard’s men follow them and cut them down without a moment’s mercy, Anthony’s men closing on them fast, pulling out swords and knives. The Lancaster soldiers run towards the river and wade across, or swim across or, weighed down by their armor, drown in a frenzy of struggling in the reeds. They run towards the park, and Hasting’s men close up and hack at them as if they were hares at the end of a harvest when the reapers form a circle around the last stand of wheat and scythe down the frightened beasts. They turn to run towards the town, and Edward’s own troop with Edward at their head chases them like exhausted deer, and catches them for butchery. The boy they call Prince Edward, Edward of Lancaster, Prince of Wales, is among them, just outside the city walls, and they cut them all down in the charge, with flashing swords and bloodied blades among screams for mercy, without pity.

“Spare me! Spare me! I am Edward of Lancaster, I am born to be king, my mother-” The rest of it is lost in a gurgle of royal blood, as a foot soldier, a common man, puts his knife into the young prince’s throat and so ends the hopes of Margaret of Anjou and the life of her son and the Lancaster line, for the profit of a handsome belt and engraved sword.

It is no sport for the king; it is a deathly ugly business, and Edward rests on his sword, and cleans his dagger, and watches his men slit throats, cut guts, smash skulls, and break legs until the Lancaster army is crying on the ground, or has run far away, and the battle, this battle at least, is won.

But there is always an aftermath and it is always messy. Edward’s joy in the battle does not extend to killing prisoners or torturing captives. He does not even relish a judicial beheading, unlike most of the other warlords of his time. But Lancaster lords have claimed sanctuary in the Abbey of Tewkesbury and cannot be allowed to stay there or given safe conduct home. “Get them out,” Edward says curtly to Richard his brother, the two united in a desire to finish it. He turns to the Grey boys, his stepsons. “You go and find the living Lancaster lords from the battlefield and take their weapons off them and put them under arrest.”

“They claim sanctuary,” Hastings points out. “They are in the abbey, hanging on to the high altar. Your own wife survives only because sanctuary was honored. Your only son was born safe in sanctuary.”

“A woman. A baby,” Edward says curtly. “Sanctuary is for the helpless. Duke Edmund of Somerset is not helpless. He is a death-dealing traitor and Richard here will pull him out of the abbey and on to the scaffold in Tewkesbury marketplace. Won’t you, Richard?”

“Yes,” Richard says shortly. “I have a greater respect for victory than for any sanctuary,” and he puts his hand on his sword hilt and goes to break down the door of the abbey, though the abbot clings to his sword arm and begs him to fear the will of God and show mercy. The army of York does not listen. It is beyond forgiveness. Richard’s men drag out screaming supplicants, and Richard and Edward watch their men knife prisoners who are begging to be ransomed in the churchyard, where they cling to gravestones, begging the dead to save them, till the abbey steps are slippery with blood and the sacred ground smells like a butcher’s shop, as if nothing were sacred. For nothing is sacred in England anymore.

MAY 14, 1471

We are waiting for news in the Tower when the sound of cheering tells me that my husband is coming home. I run down the stone stairs, my heels clacking, the girls behind me, but when the gate opens and the horses rattle in, it is not my husband but my brother Anthony at the head of the troop, smiling at me.

“Sister, give you joy, your husband is well and has won a great battle. Mother, give me your blessing, I have need of it.”

He jumps from his horse and bows to me, and then turns to our mother and doffs his cap and kneels to her as she puts her hand on his head. There is a moment of quietness as she touches him. This is a real blessing, not the empty gesture that most families make. Her heart goes out to him, her most talented child, and he bows his fair head to her. Then he gets up and turns to me.

“I’ll tell you all about it later, but be sure he won a great victory. Margaret of Anjou is in our keeping, our prisoner. Her son is dead: she has no heir. The hopes of Lancaster are down in blood and mud. Edward would be with you, but he has marched north where there are more uprisings for Neville and Lancaster. Your sons are with him and are well and in good heart. Me, he sent here to guard you and London. The men of Kent are up against us, and Thomas Neville is supporting them. Half of them are good men, ill led, but the other half are nothing but thieves looking for plunder. The smallest and most dangerous part are those who think they can free King Henry and capture you, and they are sworn to do so. Neville is on his way to London with a small fleet of ships. I’m to see the mayor and the city fathers and organize the defense.”

“We are to be attacked here?”

He nods. “They are defeated, their heir is dead, but still they take the war onwards. They will be choosing another heir for Lancaster: Henry Tudor. They will be swearing for revenge. Edward has sent me to your defense. At the worst I am to organize your retreat.”

“Are we in real danger?”

He nods. “I am sorry, sister. They have ships and the support of France, and Edward has taken the whole army north.” He bows to me and he turns, and marches into the Tower bellowing to the constable that the mayor shall be admitted at once and that he wants a report on the Tower’s preparedness for siege.

The men come in and confirm that Thomas Neville has ships in the sea off Kent, and he has sworn he will support a march by the men of Kent by sailing up the Thames and taking London. We have just won a dramatic battle, and killed a boy, the heir to the claim, and should be safe; but we are still endangered. “Why would he do it?” I demand. “It is over. Edward of Lancaster is dead, his cousin Warwick is dead, Margaret of Anjou is captive, Henry is our prisoner held here in this very Tower? Why would a Neville have ships off Gravesend and hope to take London?”

“Because it is not over,” my mother observes. We are walking on the leads of the Tower, Baby in my arms to take the air, the girls walking with us. Mother and I, looking down, can see Anthony supervising the rolling out of cannon to face downriver, and ordering sacks of river sand to stack behind the doors and windows of the White Tower. Looking downriver we can see the men working in the docks piling sandbags and putting water buckets at the ready, fearful of fire in the warehouses when Neville brings his ships upriver.

“If Neville takes the Tower, and Edward were to be defeated in the north, then it all starts again,” my mother points out. “Neville can release King Henry. Margaret can reunite with her husband, perhaps they can make another son. The only way to end their line for sure, the only way to end these wars forever, is death. The death of Henry. We have scotched the heir; now we have to kill the father.”

“But Henry has other heirs,” I say. “Even though he has lost his son. Margaret Beaufort, for one. The House of Beaufort goes on with her son, Henry Tudor.”

My mother shrugs. “A woman,” she says. “Nobody is going to ride out to put a queen on this throne. Who could hold England but a soldier?”

“She has a son, the Tudor boy.”

My mother shrugs. “Nobody is going to ride out for a stripling. Henry Tudor doesn’t matter. Henry Tudor could never be King of England. Nobody would fight for a Tudor against a Plantagenet king. The Tudors are only half royal, and that from the French royal family. He is no threat to you.” She glances down the white wall to the barred window, where the forgotten King Henry has been returned to his prayers again. “No, once he is dead, the Lancaster line is over and we are all safe.”

“But who could bring themselves to kill him? He is a helpless man, a half-wit. Who could have such a hard heart as to kill him when he is our prisoner?” I lower my voice-his rooms are just below us. “He spends his days on his knees before a prie-dieu and gazing without speaking out of the window. To kill him would be like massacring a fool. And there are those who say he is a holy fool. There are those who say he is a saint. Who would dare murder a saint?”

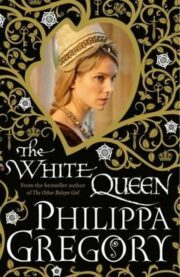

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.