The Earl of Oxford’s men, fighting for Lancaster, are on their trail at once, baying like hunting dogs, following the smell since they are still blind in the mist, with the earl cheering them on until the battlefield is behind them and the noise of the battle muffled in the fog, and the fleeing Yorkists lost, and the earl realizes that his men are running on their own account, heading for Barnet and the ale shops, already settling to a jog, wiping their swords and boasting of victory. He has to gallop around them to overtake them, block the road with his horse. He has to whip them, he has to have his captains swear at them and chivvy them. He has to lean down from his saddle and run one of his own men through the heart, and curse the others before he can bring them to a standstill.

“The battle isn’t done, you whoresons!” he yells at them. “York is still alive, so is his brother Richard, so is his brother the turncoat George! We all swore the battle would end with their deaths. Come on! Come on! You have tasted blood, you have seen them run. Come and finish them, come and finish the rest. Think of the plunder on them! They are half beaten, they are lost. Let’s make the rest run, let’s make them skip. Come on, lads, come on, let’s go, let’s see them run like hares!”

Driven into order and persuaded into ranks, the men turn and the earl dashes them at a half run back from Barnet towards the battle, his flag before him with its emblem of the Streaming Sun proudly raised. He is blinded by the mist, and desperate to rejoin Warwick, who has promised wealth to every man at his side today. But what de Vere of Oxford does not know, as he leads his troop of nine hundred men, is that the battle lines have swung round. The breaking of the York right wing and their pressing forward of their left has pushed the battlefield off the ridge, and the line of battle now runs up and down the London road.

Edward is at the heart of it still; but he can feel he is losing ground, dropping back off the road as Warwick’s men push them harder and harder. He starts to feel the sense of defeat, and this is new to him: it tastes like fear. He can see nothing in the mist and the darkness but the attackers who come, one after the other, out of the mist before him, and he responds with the instincts of a blind man to the rush of the men who come, and then come again, and again, with a sword or an axe or sometimes a scythe.

He thinks of his wife and his baby son, waiting for him and depending on his victory. He has no time to think what will happen to them if he fails. He can feel his own soldiers around him, giving way, as if they are being thrust back by the sheer weight of Warwick’s extra men. He can feel himself wearying at the unstoppable approach of his enemies, the constant demand that he should swing, thrust, spear, kill: or be killed. In the rhythm of his endurance he has a glimpse, almost a vision it is so bright, of his brother Richard: swinging, spearing, going on and on, and yet feeling his sword arm grow tired and fail. He has a picture in his mind of Richard alone on a battlefield, without him, turning to face a charge without a friend at his side, and it makes him angry and he bellows, “York! God and York!”

De Vere of Oxford, bringing his troops in at a run, gives the order to charge, seeing the battle line before him, expecting to take his men into the rear of the York lines, knowing he will wreak havoc, coming out of the mist at them, as good as fresh Lancaster reinforcements, as terrifying as an ambush. In the darkness they rush, swords and weapons drawn and already bloody, into the rear-not of the York soldiers-but of his own army, the Lancaster line, who have turned in the battle and are off the hill.

“Traitor! Treason!” screams a man, stabbed from behind, who looks round and sees de Vere. A Lancastrian officer looks over his shoulder and sees the most dreaded sight on the battlefield: fresh soldiers, coming up from the rear. In the mist he cannot see the flag clearly, but he sees, he is sure he sees, the Sun in Splendor, the York standard, fluttering proudly over fresh troops who are running up the road from Barnet, their swords out before them, battle-axes swinging, their mouths gaping as they bellow in their powerful charge. The banner of the Streaming Sun of Oxford, he mistakes for the emblem of York. He and his men have soldiers of York before them, pressing them hard, fighting like men with nothing to lose, but more and more of them coming out of the mist, from behind, like an army of specters, is more than any man can stand.

“Turn! Turn!” Somebody bellows in a panic, and another voice shouts, “Regroup! Regroup! Fall back!” And the orders are right, but the voices are filled with panic and the men turn from the York enemy before them to find another army behind them. They cannot recognize their allies. They think themselves surrounded and outnumbered and certain of death, and the heart goes out of them in a rush.

“De Vere!” shouts the Earl of Oxford, seeing his men attacking his own side. “De Vere! For Lancaster! Hold! Hold! In the name of God, hold!” But it is too late. Those who now recognize the Oxford standard with the Streaming Sun, and see de Vere laying about him in the middle of the confusion, and shouting to bring his men to order, think that he has turned his coat in midbattle-as men do-and those who are close enough, his old friends, turn on him like furious dogs to kill him as a thing worse than the enemy: a traitor on the battlefield. But in the mist and the chaos most of the Lancaster forces know only that an untold enemy is before them, pressing forward with soldiers of clouds, and now a fresh battalion has come from behind, and the darkness and fog on the road could hide more on every side. Who knows how many soldiers will rise out of the river? Who knows what horror, that Edward, married to a witch, might conjure from rivers and springs and streams? They can hear the sounds of battle and the screams of the wounded; but they cannot see their lords, they cannot recognize their commanders. The battlefield is shifting; they cannot even be sure of their comrades in the eerie half-light. Hundreds throw down their weapons and start to run. Everyone knows that this is a war in which no prisoners will be taken. It is death to be on the losing side.

Edward, stabbing and slicing, in the very heart of the battle, William Hastings on his shield arm, his sword out, his knife in his other hand, bellows, “Victory to York! Victory to York!” and his soldiers believe that mighty shout, and so does the Lancaster army, attacked from the front in darkness, attacked from the rear in mist, and now leaderless, as Warwick shouts for his page to save him, flings himself on his waiting horse, and gallops away.

It is a signal for the battle to break into a thousand adventures. “My horse!” Edward yells for his page. “Get me Fury!” And William cups his hands and throws the king upwards into the saddle, seizes his own bridle, scrambles onto his own charger, and races after his lord and master and dearest friend, and the York lords go at a headlong gallop after Warwick, cursing him for getting away.

My mother straightens up with a sigh, and together the two of us close the window. We are both pale from watching all night. “It is over,” she says with certainty. “Your enemy is dead. Your first and most dangerous enemy. Warwick will make no more kings. He will have to meet the King of Heaven and explain what he thinks he has been doing to this poor kingdom here below.”

“My boys are safe, I think?”

“I am sure of it.”

My hands are curled into claws like a cat. “And George, Duke of Clarence?” I ask. “What do you think for him? Tell me he is dead on the battlefield!”

My mother smiles. “He is on the winning side as usual,” she says. “Your Edward has won this battle, and loyal George is at his side. You may find that you have to forgive George for the death of your father and brother. I may have to leave my vengeance to God. George may survive. He is the king’s own brother, after all. Would you kill a royal prince? Could you bring yourself to kill a prince of the House of York?”

I open my jewelry box and take out the black enameled locket. I press the little catch and open it. There are the two names-George, Duke of Clarence, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick-written on the scrap of paper torn from my father’s last letter. The letter that he wrote in hope to my mother, speaking of his ransom, never dreaming that those two, whom he had known all his life, would kill him for no better reason than spite. I tear it in half and the piece that says Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, I scrunch in my hand. I do not even trouble to throw it into the fire. I let it fall on the floor and I tread it into the rushes. It can be dust. The name of George I put back in my locket and into my jewelry case. “George will not survive,” I say flatly. “If I myself have to hold a pillow over his face when he is sleeping in bed under my roof, a guest in my own house, under my protection, my husband’s beloved kin. George will not survive. A son of the House of York is not inviolate. I will see him dead. He can be sweetly sleeping in his bed in the Tower of London itself and I will still see him dead.”

Two days I have with Edward when he comes home from the battle, two days when we move back to the royal apartments at the Tower, hastily cleaned and poor Henry’s things tossed to one side. Henry, the poor mad king, is returned to his old chambers with the bars on the windows, and kneels in prayer. Edward eats as if he has starved for weeks, wallows like Melusina in a deep long bath, takes me without grace, without tenderness, takes me as a soldier takes his doxy, and sleeps. He wakes only to announce to the London citizens that stories of Warwick’s survival are untrue: he saw the man’s body himself. He was killed while he was escaping from the battle, fleeing like a coward, and Edward orders that this body be shown in St. Paul’s Cathedral so that there can be no doubt that the man is dead. “But I’ll have no dishonoring of him,” he says.

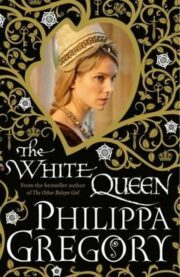

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.