Hastings leans out of the saddle towards him. “And keep that to yourself too,” he says. He nods the boys away, and turns to Edward. “Shall we fall back, wait for morning? Perhaps fall back to London? Hold the Tower? Set a siege? Hope for reinforcements from Burgundy?”

Edward shakes his head. “We’ll go on.”

“If the boys are right, and Warwick is on high ground, with double our numbers and waiting for us…” Hastings does not need to finish the prediction. Edward’s only hope against a greater army was surprise. Edward’s battle style is the rapid march and the surprise attack, but Warwick knows this. It was Warwick who taught Edward his generalship. He is thoroughly prepared for him. The master is meeting his pupil and he knows all the tricks.

“We’ll go on,” Edward says.

“We won’t see where we’re going in half an hour,” Hastings says.

“Exactly,” Edward replies. “And neither will they. Have the men march up in silence, give the order: I want absolute silence. Have them line up, battle-ready, facing the enemy. I want them in position for dawn. We’ll attack with first light. Tell them no fires, no lights: silence. Tell them that word is from me. I shall come round and whisper to them. I want not a word.”

George and Richard, Hastings and Anthony nod at this and start to ride up and down the line, ordering the men to march in utter silence and, when the word is given, to set camp at the foot of the ridge, facing the Warwick army. Even as they set off in silence up the road, the day gets darker and the horizon of the ridge and the silhouettes of the standards disappear into the night sky. The moon is not yet risen, the world dissolves into black.

“That’s all right,” Edward says, half to himself, half to Anthony. “We can hardly see them, and they are up against the sky. They won’t see us at all, looking downhill into the valley; all they will see is darkness. If we’re lucky, and it is misty in the morning, they won’t know we are here at all. We will be in the valley, hidden by cloud. They will be where we can see them, like pigeons on a barn roof.”

“You think they will just wait till morning?” Anthony asks him. “To be picked off like pigeons on a barn roof?”

Edward shakes his head. “I wouldn’t. Warwick won’t.”

As if to agree, there is a mighty roar, terribly close, and the flames of Warwick’s cannon spit into the darkness, illuminating, in a tongue of yellow fire, the dark waiting army massed above them.

“Dear God, there are twenty thousand of them at least,” Edward swears. “Tell the men to keep silent, pass the word. No return fire, tell them, I want them as mice. I want them as sleeping mice.”

There is a low laugh as some joker gives a whispered mouse squeak. Anthony and Edward hear the hushed command go down the line.

The cannons roar again and Richard rides up, his horse black in the darkness, all but invisible. “Is that you, brother? I can see nothing. The shot is going clear over our heads, praise God. He has no idea where we are. He has the range wrong; he thinks we are half a mile farther back.”

“Tell the men to keep silent and he won’t know till morning,” Edward says. “Richard, tell them they must lie low: no lights, no fires, absolute silence.” His brother nods and turns into the darkness again. Edward summons Anthony with a crook of his finger. “Take Richard and Thomas Grey, and get a good mile away; light two or three small fires, spaced out, like we were setting up camp where the shot is falling. Then get clear of them. Give them something to aim at. The fires can die down at once: don’t go back to them and get yourself hit. Just keep them thinking we are distant.”

Anthony nods and goes.

Edward slides from his horse Fury, and the page boy steps forward and takes the rein. “See he is fed, and take the saddle off him, and drop the bit from his mouth but leave the bridle on,” Edward orders. “Keep the saddle at your side. I don’t know how long a night we will have. And then you can rest, boy, but not for long. I shall need him ready a good hour before dawn, maybe more.”

“Yes, Sire,” the lad says. “They’re passing out feed and water for the horses.”

“Tell them to do it in silence,” the king repeats. “Tell them I said so.”

The lad nods, and takes the horse a little way from where the lords are standing.

“Post a watch,” Edward says to Hastings. The cannons roar out again, making them jump at the noise. They can hear the whistle of the balls overhead and then the thud as they fall too far south, well behind the line of the hidden army. Edward chuckles. “We won’t sleep much, but they won’t sleep at all,” he says. “Wake me after midnight, about two.”

He swings his cloak from his shoulders and spreads it on the ground. He pulls his hat from his head and puts it over his face. In moments, despite the regular bellow of the cannon and the thud of the shot, he is asleep. Hastings takes his own cloak and drapes it, as tenderly as a mother, over the sleeping king. He turns to George, Richard, and Anthony, “Two-hour watches each?” he asks. “I’ll take this one, then I’ll wake you, Richard, and you and George can check the men, and send out scouts, then you, Anthony.” The three men nod.

Anthony wraps his cloak around him and lies down near to the king. “George and Richard together?” he asks softly of Hastings.

“I would trust George as far as I would throw a cat,” Hastings says quietly. “But I would trust young Richard with my life. He will keep his brother on our side until battle is joined. And won, God willing.”

“Bad odds,” says Anthony thoughtfully.

“I’ve never known worse,” Hastings says cheerfully. “But we have right on our side, and Edward is a lucky commander, and the three sons of York are together again. We might survive, please God.”

“Amen to that.” Anthony crosses himself, and goes to sleep.

“Besides,” Hastings says quietly to himself, “there’s nothing else we can do.”

I do not sleep in the sanctuary at Westminster, and my mother keeps a vigil with me. A few hours before dawn, when it is at its very darkest and the moon is going down, my mother swings open the casement window and we stand side by side as the great dark river goes by. Gently I breathe out into the night and in the cold air my breath makes a cloud, like a mist. My mother beside me sighs and her breath gathers with mine and swirls away. I breathe out again and again, and now the mist is gathering on the river, gray against the dark water, a shadow on blackness. My mother sighs, and the mist is rolling out down the river, obscuring the other bank, holding the darkness of the night. The starlight is hidden by it, as the mist thickens into fog and starts to spread coldly along the river, through the streets of London, and away, north and west, rolling up the river valleys, holding the darkness into the low ground, so that even though the sky slowly lightens, the land is still shrouded, and Warwick’s men, on the high ridge outside Barnet, waking in the cold hour before dawn, looking down the slope for their enemy, can see nothing below them but a strange inland sea of cloud that lies in heavy bands along the valley, can see nothing of the army that is enveloped and silent in the obscuring darkness beneath them.

“Take Fury,” Edward says to the page quietly. “I fight on foot. Get me my battle-axe and sword.” The other lords-Anthony, George, Richard, and William Hastings, are already armed for the slugging terror of the day, their horses taken out of range, saddled and bridled, prepared-though no one says it-for flight if everything should go wrong, or for a charge if things go well.

“Are we ready now?” Edward asks Hastings.

“As ready as ever,” William says.

Edward glances up at the ridge, and suddenly says, “Christ save us. We’re wrong.”

“What?”

The mist is broken for just a small gap and it shows the king that he is not drawn up opposite Warwick’s men, troop facing troop, but too far to the left. The whole of Warwick’s right wing has nothing against them. It is as if Edward’s army is too short by a third. Edward’s army overlaps slightly to the left. His men there will have no enemy: they will plunge forward against no resistance and break the order of the line, but on his right he is far too short.

“It’s too late to regroup,” he decides. “Christ help us that we are starting wrong. Sound the trumpets; our time is now.”

The standards lift up, the pennants limp in the damp air, rising out of the mist like a sudden leafless forest. The trumpets bellow, thick and muffled in the darkness. It is still not dawn, and the mist makes everything strange and confusing. “Charge,” says Edward, though his army can hardly see his enemy, and there is a moment of silence when he senses the men are as he is, weighted down with the thick air, chilled to their bones with the mist, sick with fear. “Charge!” Edward bellows, and plows his way uphill, as with a roar his men follow him to Warwick’s army, who, starting up out of sleep, eyes straining, can hear them coming, and see glimpses now and then, but can be certain of nothing until, as if they have burst through a wall, the army of York with the king, toweringly tall, at their head, whirling a battle-axe, comes at them like a horror of giants out of the darkness.

In the center of the field the king presses forward and the Lancastrians fall back before him, but on the wing, that fatal empty right side, the Lancastrians can push down, bear down, outnumbering the fighting York army, hundreds of them against the few men on the right. In the darkness and in the mist the outnumbered York men start to fall, as the left wing of Warwick’s army pushes down the hill, and stabbing, clubbing, kicking, and beheading, forces its way closer and closer to the heart of the Yorkists. A man turns and runs, but gets no farther than a couple of paces before his head is burst open by a great swing from a mace, but that first movement of flight creates another. Another York soldier, seeing more and more men pouring down the hill towards them and with no comrade at his side, turns and takes a couple of steps into the safety and shelter of the mist and the darkness. Another follows him, then another. One goes down with a sword thrust through his back, and his comrade looks behind, his white face suddenly pale in the darkness, and then he throws down his weapon and starts to run. All along the line men hesitate, glance behind them at the tempting safety of the darkness, look ahead and hear the great roar of their enemy, who can sense victory, who can hardly see their hands before their faces but who can smell blood and smell fear. The unopposed Lancastrian left wing races down the hill, and the York right flank dare not stand. They drop their weapons and go like deer, running as a herd, scattering in terror.

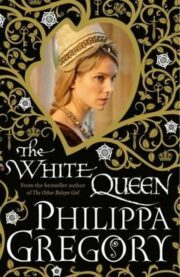

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.