“Oh, you’ll live through this,” she says. An airy wave of her hand dismisses the cramped rooms; the girls’ truckle beds in one corner; the servants’ straw mattresses on the floor in another; the poverty of the space; the chill of the cellar; the damp in the stone of the walls; the smoking fire; the dauntless courage of my children, who are forgetting that they ever lived anywhere better. “This is nothing. I expect to see us rise from this.”

“How?” I ask her disbelievingly.

She leans over and she puts her mouth to my ear. “Because your husband is not growing vines and making wine in Flanders,” she says. “He is not carding wool and learning to weave. He is equipping an expedition, making allies, raising money, planning to invade England. The London merchants are not the only ones in the country who prefer York to Lancaster. And Edward has never lost a battle. D’you remember?”

Uncertainly, I nod. Even though he is defeated and in exile, it is true that he has never lost a battle.

“So when he comes against Henry’s forces, even when they are captained by Warwick and driven on by Margaret of Anjou, don’t you think he will win?”

It is not a proper confinement, as a queen should be confined, with a ceremonial retirement from court six weeks before the date of the birth, and a closing of the shutters and a blessing of the room.

“Nonsense,” my mother says buoyantly. “You retired from daylight itself, didn’t you? Confinement? I should think no queen has ever been so confined. Who has ever been confined to sanctuary before?”

It is not a proper royal birth with three midwives and two wet nurses, and rockers and noble godmothers and mistresses of the nursery standing by, and ambassadors waiting with rich gifts. Lady Scrope is sent by the Lancaster court to make sure that I have everything I need, and I think this a gracious gesture from the Earl of Warwick to me. But I have to bring my baby into the world with no waiting husband and court at the door, and almost none to help me, and his godfathers are the Abbot of Westminster and the prior, and his godmother is Lady Scrope: the only people who are with me, neither great lords of the land nor foreign kings, the usual godfathers for a royal baby, but good and kind people who have been trapped at Westminster with us.

I call him Edward, as his father wants, and as the silver spoon from the river predicted. Margaret of Anjou, with her invasion fleet held in port by storms, sends me a message to tell me to call him John. She does not want another Prince Edward in England to rival her son. I ignore her words as from a nobody. Why would I listen to the preferences of Margaret of Anjou? My husband named him Edward, and the silver spoon came from the river with his name on it. Edward he is: Edward, Prince ofWales, he shall be, even if my mother is right and he is never Edward the king.

Among ourselves we call him Baby, and no one calls him the Prince of Wales, and I think as I drift into sleep after the birth, all warm with him in my arms, half drunk from the birthing cup that they have given me, that perhaps this baby will not be king. There have been no cannons fired for him and no bonfires lit on hilltops. The fountains and conduits of London have not run with wine, the citizens are not drunk with joy, there are no announcements of his arrival racing to the great courts of Europe. It is like having an ordinary baby, not a prince. Perhaps he will be an ordinary boy and I will become an ordinary woman again. Perhaps we will not be great people, chosen by God, but just happy.

WINTER 1470-71

We spend Christmas in sanctuary. The London butchers send us a fat goose, and my boys and little Elizabeth and I play cards and I make sure that I lose a silver sixpence to her, and send her to bed thrilled to be a serious gamester. We spend Twelfth Night in sanctuary, and Mother and I compose a play for the children, with costumes and masks and enchantments. We tell them our family story of Melusina, the beautiful woman, half girl, half fish, who is found in the fountain in the forest and marries a mortal for love. I wrap myself in a sheet, which we tie at the feet to make a great tail, and I let down my hair, and when I rise up from the floor, the girls are transported by the fish woman Melusina and the boys applaud. My mother enters with a paper horse’s head taped on the stick of a broom, wearing the doorman’s jerkin and a paper crown. The girls don’t recognize her at all and watch the play as if we were paid mummers at the greatest court in the world. We tell them the story of the courtship of the beautiful woman who is half fish, and how her lover persuades her to leave her watery fountain in the wood and take her chance in the great world. We tell only half the story: that she lives with him and gives him beautiful children and they are happy together.

There is more to the story than this, of course. But I find that I don’t want to think about marriages for love that end in separation. I don’t want to think about being a woman who cannot live in the new world that is being made by men. I don’t want to think of Melusina rising from her fountain and confining herself to a castle while I am held in sanctuary, and all of us, daughters of Melusina, are trapped in a place where we cannot wholly be ourselves.

Melusina’s mortal husband loved her, but she puzzled him. He did not understand her nature, and he was not content to live with a woman who was a mystery to him. He allowed a guest to persuade him to spy on her. He hid behind the hangings in her bath house and saw her swim beneath the water of her bath, saw-horrified-the gleam of ripple on scales, learned her secret: that although she loved him, truly loved him, she was still half woman and half fish. He could not bear what she was, and she could not help but be who she was. So he left her, because in his heart he feared that she was a woman with a divided nature-and he did not realize that all women are creatures of divided nature. He could not stand to think of her secrecy, that she had a life hidden from him. He could not, in fact, tolerate the truth that Melusina was a woman who knew the unknown depths, who swam in them.

Poor Melusina, who tried so hard to be a good wife, had to leave the man who loved her and go back to the water, finding the earth too hard. Like many women, she was unable to fit exactly with her husband’s view. Her feet hurt: she could not walk in the path of her husband’s choosing. She tried to dance to please him, but she could not deny the pain. She is the ancestress of the royal house of Burgundy, and we, her descendants, still try to walk in the paths of men, and sometimes we too find the way unbearably hard.

I hear that the new court has a merry Christmas feast. Henry the king is back in his senses, and the House of Lancaster is triumphant. From the windows of the sanctuary we can see the barges going up and down the river as the noblemen go from their riverside palaces to Whitehall. I see the Stanley barge go by. Lord Stanley, who kissed my hand at my coronation tournament, and told me his motto was “Sans Changer,” was one of the first to greet Warwick when he landed in England. It turns out he is a Lancaster man after all; maybe he will be unchanging for them.

I see the Beaufort barge with the flag of the red dragon of Wales flying at the stern. Jasper Tudor, the great power of Wales, is taking his nephew young Henry Tudor to court to visit the king, his kinsman. Half outlaw, half prince. Jasper will be back in the castles of Wales again, and Lady Margaret Beaufort will weep tears of joy all over her fourteen-year-old son, Henry Tudor, I don’t doubt. She was parted from him when we put him with good York guardians, the Herberts, and she had to endure the prospect of his marrying the Yorkist Herbert girl. But now William Herbert lies dead in our service, and Margaret Beaufort has her son back in her keeping. She will be pushing him forward at court, pushing him forward for favors and places. She will want his titles restored; she will want his inheritance guaranteed. George, Duke of Clarence, stole both the title and the lands, and she will have named them in her prayers ever since. She is a most ambitious woman, and determined mother. I don’t doubt she will have the earldom of Richmond off George within the year and, if she can, her son will be named as the Lancaster heir after the prince.

I see Lord Warwick’s barge, the most beautiful on the river, his rowers going in time to the beat of the drummer in the stern, moving swiftly against the tide as if nothing can stop his onward progress, not even the flow of the river. I even make him out, standing in the prow of the boat as if he would rule the very water of the river, his hat pulled off and held in his hand so that he can feel the cold air in his dark hair. I purse my lips to whistle up a wind, but I let him go. It makes no difference.

Warwick’s older daughter Isabel may be hand in hand with my brother-in-law George in the seats at the back of the barge as they go past my subterranean prison. Perhaps she remembers the Christmas that she came to court as an unwilling bride and I was kind to her, or perhaps she prefers to forget the court where I was the Queen of the White Rose. George will know I am here, the wife of his brother, the woman who stayed loyal when he did not: living in poverty, living in half darkness. He will know I am here; he may even feel me watching him, my narrowed eyes overlooking him-this man who was once George of the House of York, and is now a favored kinsman at the court of Lancaster.

My mother puts her hand on my arm. “Don’t ill wish them,” she warns me. “It comes back on you. It is better to wait. Edward is coming. I don’t doubt it. I don’t doubt him for a moment. This time will be like a bad dream. It is as Anthony says: shadows on the wall. What matters is that Edward musters an army big enough to defeat Warwick.”

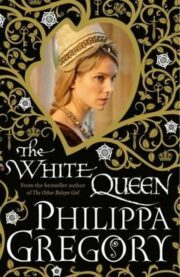

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.