“If only someone could tell him that he was welcome at home, then you would have your son back, the brothers would be reunited, York would fight for York once more, and George would lose nothing. He would be brother to the King of England, and he would be Duke of Clarence as he has always been. We could undertake that Edward would restore him. There lies his future. This other way he is-what would one call him?” She pauses to wonder what one would call Cecily’s favorite son, then she finds the words: “An utter numpty.”

The king’s mother rises to her feet; my mother gets up too. I stay seated, smiling up at her, letting her stand before me. “I always so enjoy talking with you both,” she says, her voice trembling with anger.

Now I rise, my hand on my spreading belly, and I wait for her to curtsey to me. “Oh, me too. Good day, My Lady Mother,” I say pleasantly.

And so it is done, as easily as an enchantment. Without another word said, without Edward even knowing, a lady from the king’s mother’s court decides to visit her great friend, George’s wife, poor Isabel Neville. The lady, heavily veiled, takes a boat, goes to Angers, finds Isabel, wastes no time on her crying in her room, finds George, tells him of his mother’s tender love and her concerns for him. George tells her in return of his increasing discomfort with the allies to whom he is not only sworn but also married. God, he thinks, does not bless their union since their baby died in the storm, and nothing has gone right for him since he married Isabel. Surely, nothing as unpleasant as this should ever happen to George? Now he finds himself in the company of his family’s enemies and-far worse for him-in second place again. Turncoat George says that he will come to England with the invading army of Lancaster, but as soon as he sets foot in his beloved brother’s kingdom he will tell us where they have landed, and what is their strength. He will seem to stand by them as brother-in-law to the Lancaster Prince of Wales until the battle is joined, and then he will attack them from behind, and fight his way through to his brothers once more. He will be a son ofYork, one of the three sons of York again. We can rely on him. He will destroy his present friends, and his wife’s own family. He is loyal to York. In his innermost heart, he has always been loyal to York.

My husband brings this encouraging news to me, unaware that this is the doing of women, spinning their toils around men. I am resting on my daybed, one hand on my belly, feeling the baby move.

“Isn’t this wonderful?” he asks me, truly delighted. “George will come back to us!”

“I know that you love George,” I say. “But even you have to admit he is an absolute crawling thing, loyal to no one.”

My generous-hearted husband smiles. “Oh, he is George,” he says kindly. “You can’t be too hard on him. He has always been everyone’s favorite; he has always been one to please himself.”

I find a smile in return. “I am not too hard on him,” I say. “I am glad he has come back to you.” And inwardly, I say to myself: But he is a dead man.

SUMMER 1470

I am running behind my husband, my hand on my large belly, down the long winding corridors of the Palace of Whitehall. Servants run behind us carrying goods. “You can’t go. You swore to me you would be with me for the birth of our baby. It will be a boy, your son. You must be with me.”

He turns, his face grave. “Sweetheart, our son will have no kingdom if I don’t go. Warwick’s brother-in-law, Henry Fitzhugh, has raised Northumberland. There’s no doubt in my mind that Warwick will strike in the north, and then Margaret will land her army in the south. She will come straight to London to free her husband from the Tower. I have to go, and I have to go fast. I have to deal with the one and then turn and march south to catch the other before she comes here for you. I don’t dare even stop for the pleasure of arguing with you.”

“What about me? What about me and the girls?”

He is muttering orders to the clerk, who runs behind him with a writing desk as he strides towards the stables. He pauses to shout orders at his equerries. Soldiers are rushing to the armory to draw their weapons and breastplates; sergeants are bawling at them to fall in. The great wagons are being loaded again with tents, weapons, food, gear. The great army of York is on the march again.

“You have to go to the Tower.” He swings round to order me. “I have to know you are safe. All of you, your mother as well, go to the royal rooms in the Tower. Prepare for the baby there. You know I will come to you as soon as I can.”

“When the enemy is in Northumberland? Why should I go to the Tower when you are riding out to fight an enemy hundreds of miles away?”

“Because only the devil knows for sure where Warwick and Margaret will land,” he says briefly. “I’m guessing they’ll split into two battles and land one to support the uprising in the north and the other in Kent. But I don’t know. I’ve not heard from George. I don’t know what they plan. Suppose they sail up the Thames while I am fighting in Northumberland? Be my love, be brave, be a queen: go to the Tower with the girls and keep yourselves safe. Then I can fight and win and come home to you.”

“My boys?” I whisper.

“Your boys will come with me. I shall keep them as safe as I can, but it is time they played their part in our battles, Elizabeth.”

The baby turns inside me as if he is protesting too, and I am silenced by the heave of the movement. “Edward, when will we ever be safe?”

“When I have won,” he says steadily. “Let me go and win now, beloved.”

I let him go. I think no power in the world would have stopped him, and I tell the girls that we are staying in London at the Tower, one of their favorite palaces, and that their father and their half brothers have gone to fight the bad men who still hanker after the old King Henry, though he is a prisoner at the Tower himself, silent in his rooms on the floor just below us. I tell them that their father will come home safe to us. When they cry for him in the night, for they have bad dreams about the wicked queen and the mad king, and their bad uncle Warwick, I promise them that their father will defeat the bad people and come home. I promise he will bring the boys safely back. He has given his word. He has never failed. He will come home.

But this time, he does not.

This time, he does not.

He and his brothers in arms, my brother Anthony, his brother Richard, his beloved friend Sir William Hastings, and his loyal supporters, are shaken awake at Doncaster in the early hours of the morning by a couple of the king’s minstrels who, coming drunkenly home from whoring, happen to glance over the castle walls and see torches on the road. The enemy advance guard, marching at night, a sure sign of Warwick in command, is only an hour away, perhaps only moments away, coming to snatch the king before he can meet with his army. The whole of the north is up against the king and ready to fight for Warwick, and the royal party will be taken in a moment. Warwick’s influence runs deep and wide in this part of the world, and Warwick’s brother and Warwick’s brother-in-law have turned out against Edward and are fighting for their kinsman and for King Henry, and will be at the castle gate within an hour. There is no doubt in anyone’s mind that this time Warwick will not take prisoners.

Edward dispatches my boys to me, and then he, Richard, Anthony, and Hastings fling themselves on their horses and ride away in the night, desperate not to be taken by Warwick or his kinsmen, certain that this time there will be a summary execution for them. Warwick tried once to capture and keep Edward, as we have captured and kept Henry, and learned that there is no victory as final as death. He will never again imprison Edward and wait for everyone to concede defeat. This time he wants him dead.

Edward rides out into the darkness with his friends and kinsmen and has no time to send to me, to tell me where to meet him; he cannot even write to me to tell me where he is going. I doubt that he knows himself. All he is doing is getting away from certain death. Thoughts of how to return will come later. Now, tonight, the king is running for his life.

AUTUMN 1470

The news comes to London in unreliable rumors, and it is all, always bad. Warwick lands in England, as Edward predicted, but what he did not predict is the rush of nobles to the traitor’s side, in support of the king they have left to rot in the Tower for the last five years. The Earl of Shrewsbury joins him. Jasper Tudor-who can raise most of Wales-joins him. Lord Thomas Stanley-who took the ruby ring at my coronation joust and told me that his motto was “Without Changing”-joins him. A whole host of lesser gentry follow these influential commanders, and Edward is swiftly outnumbered in his own kingdom. All the Lancaster families are finding and polishing their old weapons, hoping to march out to victory once again. It is as he warned me: he could not spread out the wealth quickly enough, fairly enough, to enough people. We could not spread the influence of my family far enough, deep enough. And now they think they will do better under Warwick and the mad old king than under Edward and my family.

Edward would have been killed on the spot if they had caught him; but they have missed him-that much is clear. But nobody knows where he is; and someone comes to the Tower once a day to assure me that they have seen him and that he was dying of his wounds, or that they have seen him and he is fleeing to France, or that they have seen him on a bier and he is dead.

My boys arrive at the Tower travel-stained and weary, furious that they did not get away with the king. I try not to hang on to them, or kiss them more often than morning and night, but I can hardly believe that they have come safely back to me. Just as I cannot believe that my husband and my brother have not.

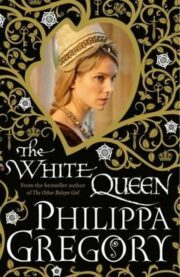

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.