She breathes a long sigh, as if she is too tired for anything more. “And yet I should know. Of all the people in the world, I should have known. I have the Sight, I should have seen it all, but some things are too dark to foresee. These are hard times, and England is a country of sorrows. No mother can be sure that she will not bury her sons. When a country is at war, cousin against cousin, brother against brother, no boy is safe.”

I sit back on my heels. “The king’s mother, Duchess Cecily, shall know this pain. She will have this pain that you are feeling. She will know the loss of her son George,” I spit. “I swear it. She will see him die the death of a liar and a turncoat. You have lost a son and so shall she, my word on it.”

“So will you, by that rule,” my mother warns me. “More and more deaths, and more feuds, and more fatherless children, and more widowed brides. Do you want to mourn for your missing son in future days, as I am doing now?”

“We can reconcile after George,” I say stubbornly. “They must be punished for this. George and Warwick are dead men from this day. I swear it, Mother. They are dead men from this day.” I rise up and go to the table. “I will tear a corner from his letter,” I say. “I will write their deaths in my own blood on my father’s letter.”

“You are wrong,” she says quietly, but she lets me cut a corner from the letter and give it back to her.

There is a knock at the door and I wipe the tears from my face before I let my mother call “Enter,” but the door is flung open without ceremony, and Edward, my darling Edward, strolls into the room as if he had been out for a day’s hunting and thought he would surprise me by coming home early.

“My God! It is you! Edward! It is you? It is really you?”

“It is me,” he confirms. “I greet you too, My Lady Mother Jacquetta.”

I fling myself at him, and as his arms come around me, I smell his familiar scent and feel the strength of his chest, and I sob at the very touch of him. “I thought you were in prison,” I say. “I thought he was going to kill you.”

“Lost his nerve,” he says shortly, trying to stroke my back and take down my hair at the same time. “Sir Humphrey Neville raised Yorkshire for Henry, and when Warwick went against him nobody supported him; he needed me. He started to see that nobody would have George for king, and I would not sign away my throne. He hadn’t bargained for that. He didn’t dare behead me. To say truth, I don’t think he could find a headsman to do it. I am crowned king: he can’t just lop off my head as if it were firewood. I am ordained; my body is sacred. Not even Warwick dares to kill a king in cold blood.

“He came to me with the paper of my abdication, and I told him that I couldn’t see my way to signing. I was happy to stay in his house. The cook is excellent and the cellar better. I told him I was happy to move my whole court to Middleham Castle if he wanted me as a guest forever. I said I could see no reason why my rule should not run from his castle, at his expense. But that I would never deny who I am.”

He laughs, his loud confident laugh. “Sweetheart, you should have seen him. He thought if he had me in his power, that he had the crown at his bidding. But he found me unhelpful. It was as good as a mumming to see him puzzle as to what to do. Once I heard you were safely in the Tower I wasn’t afraid of anything. He thought I would break when he took hold of me, and I didn’t even bend. He thought I was still the little boy who adored him. He didn’t realize that I am a grown man. I was a most agreeable guest. I ate well, and when friends came to see me, I demanded that they be entertained royally. First I asked to walk in the gardens, then in the forest. Then I said I should like to ride out, and what would be the harm in letting me go hunting? He started to let me ride out. My council came and demanded to see me, and he did not know how to refuse them. I met them and passed the odd law or two so that everyone knew nothing had changed, I was still reigning as king. It was hard not to laugh in his face. He thought to imprison me and found instead he was merely bearing the cost of a full court. Sweetheart, I asked for a choir while I dined, and he could not see how to refuse me. I hired dancers and players. He started to see that merely holding the king is not enough: you have to destroy him. You have to kill him. But I gave him nothing; he knew I would die before I gave him anything.

“Then one fine morning-four days ago-his grooms made the mistake of giving me my own horse, my war horse Fury, and I knew he could outrun anything in their stables. So I thought I would ride a little farther, and a little faster than usual, that’s all. I thought I might be able to ride to you-and I have done.”

“It is over?” I ask incredulously. “You got away?”

He grins in his pride like a boy. “I would like to see the horse that could catch me on Fury,” he said. “They had left him in the stable for two weeks feeding him oats. I was at Ripon before I could draw breath. I couldn’t have pulled him up if I had wanted to!”

I laugh, sharing his delight. “Dear God, Edward, I have been so afraid! I thought I would never see you again. Beloved, I thought I would never ever see you again.”

He kisses my head and strokes my back. “Did I not say when we first married that I will always come back to you? Did I not say I would die in my bed with you as my wife? Have you not promised to give me a son? D’you think any prison could keep me from you, ever?”

I press my face to his chest as if I would bury myself into his body. “My love. My love. So will you go back with your guards and arrest him?”

“No, he’s too powerful. He still commands most of the north. I hope we can make peace again. He knows this rebellion has failed. He knows it is over. He is cunning enough to know that he has lost. He and George and I will have to patch together some reconciliation. They will beg my pardon, and I will forgive them. But he has learned that he cannot keep me and hold me. I am king now; he can’t reverse that. He is sworn to obey me as I have sworn to rule. I am his king. It is done. And the country has no appetite for another war between more rival kings. I don’t want a war. I have sworn to bring the country justice and peace.”

He pulls the final pins from my hair and rubs his face against my neck. “I missed you,” he said. “And the girls. I had a bad moment or two when they first took me into the castle and I was in a cell with no windows. And I am sorry about your father and brother.”

He raises his head and looks at my mother. “I am more sorry for your loss than I can say, Jacquetta,” he says frankly. “These are the fortunes of war, and we all know the risks; but they took two good men when they took your husband and son.”

My mother nods. “And what will be your terms for reconciliation with the man who killed my husband and my son? I take it you will forgive him that also?”

Edward makes a grimace at the hardness in her voice. “You will not like it,” he warns us both. “I shall make Warwick’s nephew Duke of Bedford. He is Warwick’s heir; I have to give Warwick a stake in our family, the royal family; I have to tie him in to us.”

“You give him my old title?” my mother asks incredulously. “The Bedford title? My first husband’s name? To a traitor?”

“I don’t care if his nephew has a dukedom,” I say hastily. “It is Warwick who killed my father, not the boy. I don’t care about his nephew.”

Edward nods. “There is more,” he says uncomfortably. “I shall give our daughter Elizabeth in marriage to young Bedford. She will make the alliance firm.”

I turn on him. “Elizabeth? My Elizabeth?”

“Our Elizabeth,” he corrects me. “Yes.”

“You will promise her in marriage, a child of not yet four years old, to the family of the man who murdered her grandfather?”

“I will. This has been a cousins’ war. It has to be a cousins’ reconciliation. And you, beloved, will not stop me. I have to bring Warwick to peace with me. I have to give him a great share of the wealth of England. This way I even give him a chance at his line inheriting the throne.”

“He is a traitor and a murderer, and you think you will marry my little daughter to his nephew?”

“I do,” he says firmly.

“I swear that it will never happen,” I say fiercely. “And more: I tell you this. I foresee it will never happen.”

He smiles. “I bow to your superior foreknowledge,” he says, and sweeps a magnificent bow at my mother and me. “And only time will prove your foreseeing true or false. But in the meantime, while I am King of England, with the power to give my daughter in marriage to whom I wish, I shall always do my very best to stop your enemies ducking you two as a pair of witches, or strangling you at the crossroads. And I tell you, as I am king, the only way to make you and every woman and her son in this kingdom as safe as she should be is to find a way to stop this warfare.”

AUTUMN 1469

Warwick returns to court as a beloved friend and loyal mentor. We are to be as a family that suffers occasional quarrels, but loves one another withal. Edward does this rather well. I greet Warwick with a smile as warm as a frozen fountain dripping with ice. I am expected to behave as if this man is not the murderer of my father and brother, and the jailer of my husband. I do as I am commanded: not a word of my anger escapes me, but Warwick knows without any telling that he has made a dangerous enemy for the rest of his life.

He knows I can say nothing, and his small bow when he first greets me is triumphant. “Your Grace,” he says suavely.

As ever with him, I feel at a disadvantage, like a girl. He is a great man of the world, and he was planning the fortunes of this kingdom when I was minding my manners to my lady Grey, my husband’s mother, and obeying my first husband. He looks at me as if I should still be feeding the hens at Grafton.

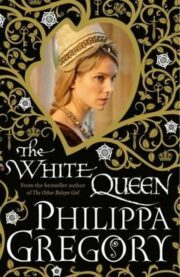

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.