When Margaret was a little girl, she thought she would be married to an English lord and live in an English castle, raising children. She even dreamed of being a nun-she shares her mother’s enthusiasm for the Church. She did not realize, when her father claimed the throne and her brother won it, that a price must always be paid for power, and it will be paid by her as well as the rest of us. She doesn’t realize yet that though men go to war it is women who suffer-perhaps more than anyone.

“I won’t marry a Frenchman. I hate the French,” she says hotly. “My father fought them; he would not have wanted me to marry a Frenchman. My brother should not think of it. I don’t know why my mother considers it. She was with the English army in France; she knows what the French are like. I am of the House of York. I don’t want to be a Frenchwoman!”

“You won’t be,” I say steadily. “That is the plan of the Earl of Warwick, and he no longer has the ear of the king. Yes, he takes French bribes and he favors France; but my advice to the king is that he should make an alliance with the Duke of Burgundy, and that will be a better alliance for you. Just think-you will be my kinswoman! You will marry the Duke of Burgundy and live in the beautiful palace at Lille. Your husband-to-be is an honored friend of the House of York, and my kinsman through my mother. He is a good friend, and from his palace you will be able to come on visits home. And when my daughters are old enough I shall send them to you, to teach them the elegant court life at Burgundy. There is nowhere more fashionable and more beautiful than the court of Burgundy. And as Duchess of Burgundy you shall be godmother to my sons. How will that be?”

She is partly comforted. “But I am of the House of York,” she says again. “I want to stay in England. At least until we have finally defeated the Lancastrians, and I want to see the christening of your son, the first York prince. Then I shall want to see him made Prince of Wales…”

“You shall come to his christening, whenever he comes to us,” I promise her. “And he will know his aunt is his good guardian. But you can further the needs of the House of York in Burgundy. You will keep Burgundy a friend to York and to England, and if ever Edward is in trouble, he will know that he can call on the Burgundy wealth and arms. And if ever again he is in danger from a false friend, he can come to you for help. You will like to be our ally over the sea. You will be our haven.”

She drops her little head on my shoulder. “Your Grace, my sister,” she says. “It is hard for me to go away. I have lost a father and I am not sure that my brother is not still in danger. I am not sure that he and George are true friends; I am not certain that George does not envy Edward, and I am afraid of what my lord Warwick might do. I want to stay here. I want to be with Edward and with you. I love my brother George; I don’t want to leave him at this time. I don’t want to leave my mother. I don’t want to leave home.”

“I know,” I say gently. “But you can be a powerful and good sister to Edward and to George as the Duchess of Burgundy. We will know that there is always one country that we can depend on to stand our friend. We will know that there is a beautiful duchess who is a Yorkist through and through. You can go to Burgundy and have sons, York sons.”

“D’you think I can found a House of York overseas?”

“You will found a new line,” I assure her. “And we will be glad to know that you are there, and we will visit you.”

She puts a brave face on it, and Warwick puts a two-faced face on it and escorts her to the port of Margate, and we wave her away, our little duchess, and I know that of all of Edward’s brothers and sisters, George the unfaithful and Richard the boy, we have just sent away the most loving, the most loyal, the most reliable Yorkist of them all.

To Warwick, this is another defeat at my hands and at the hands of my family. He promised that Margaret would have a French husband, but he has to take her to the Duke of Burgundy. He planned to make an alliance with France and he said that he had control of the decision making in England. Instead, we are to marry into the royal House of Burgundy: my mother’s family. And everyone can see that England is commanded by the Rivers family and that the king listens only to us. Warwick escorts Margaret on her wedding journey with a face as if he is sucking lemons, and I laugh behind my hand to see him overpowered and outnumbered by us, and think myself safe from his ambition and his malice.

SUMMER 1469

I am wrong, I am so wrong. We are not so powerful, we are not powerful enough. And I should have taken more care. I did not think, and I, of all people, who was afraid of Warwick before I had even met him, should have thought of his envy and his enmity. I did not foresee-and I of all queens with growing sons of my own should have foreseen-that Warwick and Edward’s bitter mother might come together and think to place another York boy on the throne in place of the first boy they had chosen, that the Kingmaker would make a new king.

I should have been more aware of Warwick, as my family pushed him out of his offices and won the lands that he might have wanted for himself. I should have seen also that George, the young Duke of Clarence, was bound to interest him. George is a son of York like Edward, but malleable, easily tempted, and above all unmarried. Warwick looked at Edward and me and the growing strength and wealth of the Riverses that I have put around Edward, and began to think that perhaps he might make another king, another king again, a king who would be more obedient to him.

Three beautiful daughters, we have, one newborn, and we are hoping-with rising anxiety-for a son, when Edward gets news of a rebel in Yorkshire calling himself Robin. Robin of Redesdale, a fanciful name meaning nothing, a petty rebel hiding himself behind a legendary name, raising troops, slandering my family, and demanding justice and freedom and the usual nonsense by which good men are tempted from minding their fields to go to their deaths. Edward pays little attention at first, and I, foolishly, think nothing of it at all. Edward is on pilgrimage with my family, my Grey sons Richard and Thomas and his young brother Richard, showing himself to the people and giving thanks to God, and I am traveling to meet him with the girls and, though we write every day, we think so little of the uprising that he does not even mention it in his letters.

Even when my father remarks to me that someone is paying these men-they are not armed with pitchforks, they have good boots and they are marching in good order-I pay him no attention. Even when he says, a few days later, that these are men who belong to someone: peasants or tenants or men sworn to a lord, I hardly listen to his hard-won wisdom. Even when he points out to me that no man takes up his scythe and thinks he will go and fight in a war; someone, his lord, has to give the order. Even then, I pay him no attention. When my brother John says that this is Warwick’s country and most likely the rebels are raised by Warwick’s men, I still think nothing of it. I have a new baby and my world revolves around her carved gold-painted crib. We are on progress in southeast England where we are beloved, the summer is fine, and I think, when I think at all, that the rebels will most likely go home in time to bring in the harvest, and the unrest will go quiet of its own accord.

I am not concerned until my brother John comes to me, his face grave, and swears that there are hundreds, perhaps thousands of men in arms, and it has to be the Earl of Warwick about his old business of making mischief, as no one else could muster so many. He is kingmaking again. Last time he made Edward to replace King Henry; this time he wants to make George, Duke of Clarence, brother to the king, the son of no importance, to replace my husband Edward. And so to replace me and mine as well.

Edward meets me at Fotheringhay, as we had arranged, quietly furious. We had planned to enjoy the beautiful house and grounds in the midsummer weather and then travel on to the prosperous town of Norwich together, for a great ceremonial entry to this most wealthy city. Our plan was to knit ourselves into the pilgrimages and feasts of the country towns, to dispense justice and patronage, to be seen as the king and queen at the heart of their people-nothing like the mad king in the Tower and his madder queen in France.

“But now I have to go north and deal with this,” Edward complains to me. “There are new rebellions coming up like springs in a flood. I thought it was one discontented squire, but the whole of the north seems to be taking up arms again. It is Warwick, it must be Warwick, though he has said not a word to me. But I asked him to come to me, and he has not come. I thought that was odd-but I knew he was angry with me-and now this very day I hear that he and George have taken ship. They have gone to Calais together. Goddamn them, Elizabeth, I have been a trusting fool. Warwick has fled from England, George with him; they have gone to the strongest English garrison, they are inseparable, and all the men who say they are out for Robin of Redesdale are really paid servants of George or Warwick.”

I am aghast. Suddenly the kingdom that had seemed quiet in our hands is falling apart.

“It must be Warwick’s plan to use all the tricks against me that he and I used against Henry.” Edward is thinking aloud. “He is backing George now, as he once backed me. If he goes on with this, if he uses the fortress of Calais as his jumping point to invade England, it will be a brothers’ war as it was once a cousins’ war. This is damnable, Elizabeth. And this is the man I thought of as my brother. This is the man who all but put me on the throne.This is my kinsman and my first ally. This was my greatest friend!”

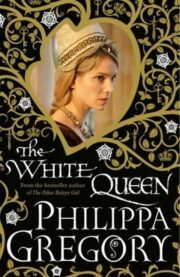

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.