“You have to do it,” he assures me. “They complain that you are a poor widow from a family of unknowns. You have to improve your family by marrying them to the nobility.”

“We are so many, I have so many sisters, I swear we will take up all the eligible young men. We will leave you with a dearth of lords.”

He shrugs. “This country has been divided into either York or Lancaster for too long. Make me another great family that will support me when York wavers, or when Lancaster threatens. You and I need to link ourselves to the nobility, Elizabeth. Give your mother free rein, we need cousins and in-laws in every county in the land. I shall ennoble your brothers, and your Grey sons. We need to create a great family around you, both for your position and for your defense.”

I take him at his word and I go to my mother and find her seated at the great table in my rooms, with pedigrees and contracts and maps all around her, like a commander raising troops.

“I see you are the goddess of love,” I observe.

She glances up at me, frowning in concentration. “This is not love; this is business,” she says. “You have your family to provide for, Elizabeth, and you had better marry them to wealthy husbands or wives. You have a lineage to create. Your task as queen is to watch and order the nobility of your country: no man must grow too great, no lady can fall too low. I know this: my own marriage to your father was forbidden, and we had to beg pardon from the king, and pay a fine.”

“I would have thought that would have put you on the side of freedom and true love?”

She laughs shortly. “When it was my freedom and my love affair: yes. When it is the proper ordering of your court: no.”

“You must be sorry that Anthony is already married now that we could command a great match for him?”

My mother frowns. “I am sorry that she is barren and in poor health,” she says bluntly. “You can keep her at court as a lady-in-waiting and she is of the best family; but I don’t think she will give us sons and heirs.”

“You will have dozens of sons and heirs,” I predict, looking at her long lists of names and the boldly drawn arrows between the names of my sisters and the names of English noblemen.

“I should do,” she says with satisfaction. “And not one of them less than a lord.”

So we have a month of weddings. Every sister of mine is married to a lord, except for Katherine, where I go one better and betroth her to a duke. He is not yet ten years old, a sulky child, Henry Stafford, the little Duke of Buckingham. Warwick had him in mind for his daughter Isabel. But as the boy is a royal ward since the death of his father, he is at my disposal. I am paid a fee to guard him, and I can do with him what I want. He is an arrogant rude boy to me; he thinks he is of such a great family, he is so filled with pride in himself that I take a pleasure in forcing this young pretender to the throne into marriage with Katherine. He regards her, and all of us, as unbearably beneath him. He thinks he is demeaned by marriage to us, and I hear he tells his friends, boasting like a boy, that he will have his revenge, and we will fear him one day, he will make me sorry that I insulted him, one day. This makes me laugh; and Katherine is glad to be a duchess even with a sulky child for a husband.

My twenty-year-old brother John, who is luckily still single, will be married to Lord Warwick’s aunt, Lady Catherine Neville. She is dowager Duchess of Norfolk, having wedded and bedded and buried a duke. This is a slap in the face to Warwick, and that alone gives me mischievous joy, and, since his aunt is all but one hundred years old, marriage to her is a jest of the most cruel sort. Warwick will learn who makes the alliances in England now. Besides, she must soon die, and then my brother will be free again and wealthy beyond belief.

For my son, my darling Thomas Grey, I buy little Anne Holland. Her mother, the Duchess of Exeter, my husband’s own sister, charges me four thousand marks for the privilege, and I note the price of her pride and pay it so that Thomas can inherit the Holland fortune. My son will be as wealthy as any prince in Christendom. I rob the Earl of Warwick of this prize too-he wanted Anne Holland for his nephew and it was all but signed and sealed; but I outbid him by a thousand marks-a fortune, a king’s fortune, which I can command and Warwick cannot. Edward makes Thomas the Marquis of Dorset to match his prospects. I shall have a match for my son Richard Grey as soon as I can see a girl who will bring him a fortune; in the meantime he will be knighted.

My father becomes an earl; Anthony does not gain the dukedom that he joked about, but he does get the lordship of the Isle of Wight; and my other brothers get their places in royal service or in the church. Lionel will be a bishop as he wanted. I use my great position as queen to put my family into power, as any woman would do, and indeed as any woman risen to greatness from nothing would be advised to do. We will have our enemies-we have to make connections and allies. We have to be everywhere.

By the end of the long process of marriage and ennoblement, no man can live in England without encountering one of my family: you cannot make a trade, plow a field, or try a case without meeting one of the great Rivers family or their dependants. We are everywhere; we are where the king has chosen to place us. And should the day come that everyone turns against him, he will find that we, the Riverses, run deep and strong, a moat around his castle. When he loses all other allies, we will still be his friends, and now we are in power.

We are loyal to him and he cleaves to us. I swear to him my faith and my love, and he knows there is no woman in the world who loves him more than I do. My brothers and my father, my cousins and my sisters, and all our new husbands and wives promise him their absolute loyalty, whatever comes, whoever comes against us. We make a new family neither Lancaster nor York; we are the Woodville family enobled as Riverses, and we stand behind the king like a wall of water. Half the kingdom can hate us, but now I have made us so powerful that I do not care.

Edward settles to the business of governing a country that is accustomed to having no king at all. He appoints justices and sheriffs to replace men killed in battle; he commands them to impose law and order in their counties. Men who have seized the chance to make war on their neighbors have to return to their own bounds. The soldiers discharged from one side or another have to go back to their homes. The warring bands who have taken their chance to ride out and terrorize must be hunted down, the roads have to be made safe again. Edward starts the hard work of making England a country at peace with itself once more. A country at peace instead of a country at war.

Then, finally, there is an end to the constant warfare when we capture the former King Henry, half lost and half-witted in the hills of Northumberland, and Edward orders him to be brought to the Tower of London, for his own safety and for ours. He is not always in his right mind, God keep him. He moves into the rooms in the Tower and seems to know where he is; he seems to be glad to be home after his wandering. He lives quietly, communing with God, a priest at his side night and day. We don’t even know if he remembers his wife or the son she told him was his; certainly, he never speaks of them nor asks for them in faraway Anjou. We don’t know for sure if he always remembers that once he was king. He is lost to the world, poor Henry, and he has forgotten everything that we have taken from him.

SUMMER 1468

Edward trusts Warwick with an embassy to France, and Warwick seizes the opportunity to get away from England and away from court. He cannot bear the rising of our tide and the slow decline of his own hopes. He plans to make a treaty with the King of France and promises him that the government of England is still in his gift; and that he is going to choose the husband for the York heiress Margaret. But he is lying, and everyone knows that his days of power are over. Edward listens to my mother, to me, and to his other advisors, who say that the dukedom of Burgundy has been a faithful friend, where France is a constant enemy, and that an alliance with Burgundy could be made for the good of trade, for the sake of our cousinship, and could be cemented with the marriage of Edward’s sister Margaret to the new duke himself: Charles, who has just inherited the rich lands of Burgundy.

Charles is a key friend to England. The Duke of Burgundy owns all the lands of Flanders, as well as his own dukedom of Burgundy, and so commands all the lowlands of the north, all the lands between Germany and France, and the rich lands in the south. They are great buyers of English cloth, merchants and allies to us. Their ports face ours across the English sea; their usual enemy is France, and they look to us for alliance. These are traditional friends of England and now-through me-kinsmen to the English king.

All this is planned without reference to the girl herself, of course; and Margaret comes to me when I am walking in the garden at Westminster Palace, all in a fluster, as someone has told her that her betrothal to Dom Pedro of Portugal is to be put aside and she is now to be sold to the highest bidder, either to Louis of France for one of the French princes, or to Charles of Burgundy.

“It’ll be all right,” I say to her, tucking her hand in mine so she can walk beside me. She is only twenty-two, and she was not raised to be the sister of a king. She is not accustomed to the way that her husband-to-be can change with the needs of the moment, and her mother, torn between her divided loyalties to her rivalrous sons, has quite failed to care for her daughters.

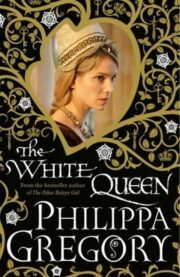

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.