“Where is the king?” I ask as we start our small procession through the gates of the town. The streets are lined on either side with townspeople, guildsmen, apprentices, and there is a cheer for my beauty and laughter at our procession. I see Anthony flush when he hears a couple of bawdy jokes, and I put my hand on his gloved fist, clenched on the pommel of his saddle. “Hush,” I say. “People are bound to make mock. This was a secret wedding, we cannot deny it, and we will have to live down the scandal. And you don’t help me at all if you look offended.”

At once he assumes the most ghastly simper. “This is my court smile,” he says out of the corner of his upturned mouth. “I use it when I talk to Warwick or the royal dukes. How d’you like it?”

“Very elegant,” I say, trying not to laugh. “Dear God, Anthony, d’you think we will get through this all right?”

“We will get through it triumphantly,” he says. “But we must stick together.”

We turn up the high street and now there are hastily made banners and pictures of saints held from the overhanging windows to welcome me to the city. We ride to the abbey; and there, in the center of his court and advisors, I see him, Edward, dressed in cloth of gold with a scarlet cape and a scarlet hat on his head. He is unmistakable, the tallest man in the crowd, the most handsome, the undoubted King of England. He sees me, and our eyes meet, and it is once again as if no one else is there. I am so relieved to see him that I give him a little wave, like a girl, and instead of waiting for me to halt my horse and dismount and approach him up the carpet, he breaks away from them all and comes quickly to my side and lifts me off my horse and into his arms.

There is a roar of delighted applause from the onlookers and a shocked silence from the court at this passionate breach of protocol.

“Wife,” he says in my ear. “Dear God, I am so glad to have you in my arms.”

“Edward,” I say. “I have been so afraid!”

“We have won,” he says simply. “We will be together forever. I shall make you Queen of England.”

“And I shall make you happy,” I say, quoting the marriage vows. “I shall be bonny and blithe at bed and board.”

“I don’t care a damn about dinnertime,” he says vulgarly, and I hide my face against his shoulder and laugh.

I still have to meet his mother; and Edward takes me to her private chambers before dinner. She was not present during my welcome from the court, and I am right to read this as her first snub, the first of many. He leaves me at her door. “She wants to see you alone.”

“How do you think she will be?” I ask nervously.

He grins. “What can she do?”

“That is the very thing I would like to know before I go in to face her,” I say dryly, and walk past him as they throw open the doors to her presence chamber. My mother and three of my sisters come with me as a makeshift court, my newly declared ladies-in-waiting, and we step forward with all the eagerness of a coven of witches dragged to trial.

The dowager Duchess Cecily is seated on a great chair covered by a cloth of estate, and she does not trouble herself to rise to greet me. She is wearing a gown encrusted with jewels at the hem and the breast, and a large square headdress that she wears proudly, like a crown. Very well, I am her son’s wife but not yet an ordained queen. She is not obliged to curtsey to me, and she will think of me as a Lancastrian, one of her son’s enemies. The turn of her head and the coldness of her smile convey very clearly that to her I am a commoner, as if she herself had not been born an ordinary Englishwoman. Behind her chair are her daughters Anne, Elizabeth, and Margaret, dressed quietly and modestly so as not to outshine their mother. Margaret is a pretty girl: fair and tall like her brothers. She smiles shyly at me, her new sister-in-law, but nobody steps forward to kiss me, and the room is as warm as a lake in December.

I curtsey low, but not very low, to Duchess Cecily, out of respect to my husband’s mother, and behind me I see my mother sweep her grandest gesture and then stand still, her head up, a queen herself, in everything but a crown.

“I will not pretend that I am happy with this secret marriage,” the dowager duchess says rudely.

“Private,” my mother interrupts smartly.

The duchess checks, amazed, and raises her perfectly arched eyebrows. “I beg your pardon, Lady Rivers. Did you speak?”

“Neither my daughter nor your son would so far forget themselves as to marry in secret,” my mother says, her Burgundy accent suddenly revived. It is the very accent of elegance and high style for the whole of Europe. She could not remind everyone more clearly that she is the daughter of the Count of Saint-Pol, Burgundian royalty by birth. She was on first-name terms with the queen, whom she alone persists in calling Margaret d’Anjou, with much emphasis on the “d” of the title. She was the Duchess of Bedford by her first marriage to a duke of the royal blood, and the head of the Lancaster court when the woman seated so proudly before us was born nothing more than Lady Cecily Neville of Raby Castle. “Of course it was not a secret wedding. I was there and so were other witnesses. It was a private wedding.”

“Your daughter is a widow and years older than my son,” Her Grace says, joining battle.

“He is hardly an inexperienced boy. His reputation is notorious. And there are only five years between them.”

There is a gasp from the duchess’s ladies and a flutter of alarm from her daughters. Margaret looks at me with sympathy, as if to say there is no escaping the humiliation to come. My sisters and I are like standing stones, as if we were dancing witches under a sudden enchantment.

“And the good thing,” my mother says, warming to her theme, “is that we can at least be sure that they are both fertile. Your son has several bastards, I understand, and my daughter has two handsome legitimate boys.”

“My son comes from a fertile family. I had eight boys,” the dowager duchess says.

My mother inclines her head and the scarf on her headdress billows like a sail filled with the swollen breeze of her pride. “Oh, yes,” she remarks. “So you did. But of that eight, only three boys left, of course. So sad. As it happens, I have five sons. Five. And seven girls. Elizabeth comes from fertile royal stock. I think we can hope that God will bless the new royal family with issue.”

“Nonetheless, she was not my choice, nor the choice of the Lord Warwick,” Her Grace repeats, her voice trembling with anger. “It would mean nothing if Edward were not king. I might overlook it if he were a third or fourth son to throw himself away…”

“Perhaps you might. But it does not concern us. King Edward is the king. The king is the king. God knows, he has fought enough battles to prove his claim.”

“I could prevent him being king,” she rushes in, temper getting the better of her, her cheeks scarlet. “I could disown him, I could deny him, I could put George on the throne in his place. How would you like that-as the outcome of your so-called private wedding, Lady Rivers?”

The duchess’s ladies blanch and sway back in horror. Margaret, who adores her brother, whispers, “Mother!” but dares say no more. Edward has never been their mother’s favorite. Edmund, her beloved Edmund, died with his father at Wakefield, and the Lancastrian victors stuck their heads on the gates of York. George, his brother, younger again, and his mother’s darling, is the pet of the family. Richard, the youngest of all, is the dark-haired runt of the litter. It is incredible that she should talk of putting one son before another, out of order.

“How?” my mother says sharply, calling her bluff. “How would you overthrow your own son?”

“If he was not my husband’s child-”

“Mother!” Margaret wails.

“And how could that be?” demands my mother, as sweet as poison. “Would you call your own son a bastard? Would you name yourself a whore? Just for spite, just to throw us down, would you destroy your own reputation and put cuckold’s horns on your own dead husband? When they put his head on the gates of York, they put a paper crown on him to make mock. That would be nothing to putting cuckold’s horns on him now. Would you dishonor your own name? Would you shame your husband worse than his enemies did?”

There is a little scream from the women, and poor Margaret staggers as if to faint. My sisters and I are half fish, not girls; we just goggle at our mother and the king’s mother head to head, like a pair of slugging battle-axe men in the jousting ring, saying the unthinkable.

“There are many who would believe me,” the king’s mother threatens.

“More shame to you then,” my mother says roundly. “The rumors about his fathering reached England. Indeed, I was among the few who swore that a lady of your house would never stoop so low. But I heard, we all heard, gossip of an archer named-what was it-” She pretends to forget and taps her forehead. “Ah, I have it: Blaybourne. An archer named Blaybourne who was supposed to be your amour. But I said, and even Queen Margaret d’Anjou said, that a great lady like you would not so demean herself as to lie with a common archer and slip his bastard into a nobleman’s cradle.”

The name Blaybourne drops into the room with a thud like a cannonball. You can almost hear it roll to a standstill. My mother is afraid of nothing.

“And anyway, if you can make the lords throw down King Edward, who is going to support your new King George? Could you trust his brother Richard not to have his own try at the throne in his turn? Would your kinsman Lord Warwick, your great friend, not want the throne on his own account? And why should they not feud among themselves and make another generation of enemies, dividing the country, setting brother against brother again, destroying the very peace that your son has won for himself and for his house? Would you destroy everything for nothing but spite? We all know the House of York is mad with ambition; will we be able to watch you eat yourselves up like a frightened cat eats her own kittens?”

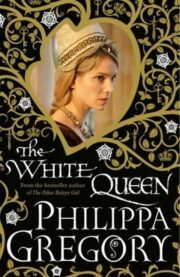

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.