Henry’s story is that there was once a poor man, a man who kept the watergate at Tournai in Flanders. He was a weak man, a bit of a drunkard, married to a common woman, a bit of a fool, and they had a son, a silly boy who ran away from home and fell into bad company, serving as a page to someone (it doesn’t matter much who or why) and went to the court of Portugal and for some reason (for who knows what silly lads will say?) passed himself off as a prince of England and everyone believed him. Then, suddenly he became a servant for a silk merchant. He learned to speak English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese (which is a little surprising but presumably not impossible). Dressed in his master’s clothes, showing off the goods for sale, parading himself like a May Day pageant in Ireland, he was again mistaken for a prince (don’t pause to ask if such a thing is likely) and was persuaded to take on the pretense all across Christendom—to what end and why is never discussed.

How such a poor ignorant boy from a common home should fool the greatest kings of Christendom, the Duchess of Burgundy, the Holy Roman Emperor, the King of France, the King of Scotland, should delight the court of Portugal and tempt the monarchs of Spain, Henry does not say. It is part of the magic of the fairy tale, like a goose-girl who is really a princess, or a girl who cannot sleep on a pea even when it is covered by twenty feather mattresses. Amazingly, this common, vulgar, ill-educated boy, the son of a drunkard and a fool, engages the richest, most cultured men in Christendom, so that they put their wealth and their armies at his disposal. How he learns to speak four languages and Latin, how he learns to read and write with an elegant hand, how he learns to hunt and joust, hawk and dance so that people admire him as a courageous graceful prince, though he was raised in the backstreets of Tournai, Henry doesn’t say. How he learns the royal smile, the casual warm acknowledgment of homage, Henry does not even consider in his long account, though of all the men in the world he would have been the most struck by this. This is a story of magic: a common boy puts on a silk shirt, and everyone falls for the illusion that he has royal blood.

As my half brother wrote to me that one time: So be it.

I receive only one private letter from Henry during this busy time as he writes and rewrites explanations of how the boy, John Perkin, Piers Osbeque, Peter Warboys—for Henry offers several different names—made his transformation to prince and back again.

I am sending his wife to join you at court, Henry writes, knowing that there is no need for him to say whose wife is joining me. You will be surprised at her beauty and elegance. You will oblige me by making her welcome and comforting her in the cruel deceit that has been played on her.

I hand his letter to his mother, who stands with her hand out, waiting impatiently to read it. Of course, the boy’s wife has been cruelly, amazingly deceived. Her husband wore a silk shirt and she was blinded by beautiful tailoring. She could not see that beneath it he was a common little boy from Flanders. Easily deluded, amazingly deluded, she saw the shirt and thought he was a prince, and married him.

PALACE OF SHEEN, RICHMOND, AUTUMN, 1497

“She is to be considered as a single woman,” My Lady the King’s Mother announces to my ladies. “I expect the marriage will be annulled.”

“On what grounds?” I ask.

“Deception,” she replies.

“In what way was she deceived?” I ask demurely.

“Obviously.” My Lady snubs me.

“Not much of a deception, if it was obvious,” Maggie whispers tartly.

“And where is her child to be housed, My Lady?” I ask.

“He is to live away from court with his nursemaid,” My Lady says. “And we are not to mention him.”

“They say that she’s very beautiful,” my sister Cecily volunteers, sweet as Italian powders.

I smile at Cecily, my face and my eyes quite blank. If I want to save my throne, my freedom, and the life of the baby of the boy who calls himself my brother, I am going to have to endure the arrival of Lady Katherine, a beautiful, single princess, and much, much more.

I can hear the noise of her guard outside the door, the quick exchange of passwords, and then the door is thrown open. “Lady Katherine Huntly!” the man bellows quickly, as if they fear that someone might say: “Queen Katherine of England.”

I stay seated, but my Lady the King’s Mother surprises me by rising from her chair. My ladies sink down, as low as if they were honoring a woman of full royal blood, as the young woman comes into the room.

She is wearing black, in mourning as if she is a widow, but her cape and gown are beautifully made, beautifully tailored. Who would have thought that Exeter had such seamstresses? She is wearing a black satin dress trimmed with rich black velvet, a black hat on her head, a black riding cloak over her arm, she is wearing gloves of black embroidered leather. Her eyes are dark, hollowed in her pale face, her skin utterly clear, like the finest palest marble. She is a beautiful young woman in her early twenties. She curtseys low to me and I see her scanning my face, as if she is looking for some resemblance to her husband. I give her my hand and I rise to my feet and I kiss one cool cheek and then another for she is cousin to the King of Scotland, whoever she married, whatever the quality of the silk of his shirt. I feel her hand tremble in mine and again I see that wary look as if she would read me, as if she would know where I stand in this unfolding masque which her life has become.

“We welcome you to court,” My Lady says. There is no careful reading needed for My Lady. She is doing what her son requested, welcoming Lady Katherine to court with such kindliness that even the most hospitable host would have to wonder why we are making such a fuss of this woman, the disgraced wife of our defeated enemy.

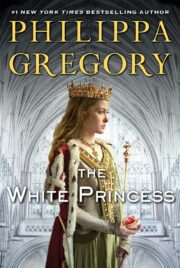

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.