I think of my little brother, the child that my mother loved. I think of him looking at picture books on my lap, or running around the inner courtyard at Sheen with a little wooden sword. I think that it will not be possible for me to see his merry smile and his warm hazel eyes and not reach out to him.

“You will deny him,” Henry says flatly. “Or I will deny you. If you ever, by so much as a word, the whisper of a word, the first letter of a word, give anyone, anyone to understand that you recognize this imposter, this commoner, this false boy, then I will put you aside and you will live and die in Bermondsey Abbey as your mother did. In disgrace. And you will never see any of your children again. I will tell them—each one of them—that their mother is a whore and a witch. Just like her mother, and her mother before that.”

I face him, I rub his kiss from my mouth with the back of my hand. “You need not threaten me,” I say icily. “You can spare me your insults. I know my duty to my position and to my son. I’m not going to disinherit my own son. I will do as I think right. I am not afraid of you, I have never been afraid of you. I will serve the Tudors for the sake of my son—not for you, not for your threats. I will serve the Tudors for Arthur—a true-born king of England.”

He nods, relieved to see his safety in my unquestionable love for my boy. “If any one of you Yorks speaks of the boy other than as a young fool and a stranger, I will have him beheaded that same day. You will see him on Tower Green with his head on the block. The moment that you or your sisters or your cousin or any of your endless cousins or bastard kinsmen recognize the boy is the moment that you sign the warrant for his execution. If anyone recognizes him then they die and he dies. D’you understand?”

I nod my head and I turn away from him. I turn my back on him as if he were not a king. “Of course I understand,” I say contemptuously over my shoulder. “But if you are going to continue to claim that he is the son of a drunken boatman from Tournai, you must remember not to have him beheaded like a prince on Tower Green. You’ll have to have him hanged.”

I shock him, he chokes on a laugh. “You’re right,” he says. “His name is to be Pierre Osbeque, and he was born to die on the gallows.”

With ironic respect I turn back to him and sweep a curtsey, and in this moment I know that I hate my husband. “Clearly, we will call him whatever you wish. You can name the young man’s corpse whatever you wish, that will be your right as his murderer.”

We do not reconcile before he rides out and so my husband goes out to war with no warm farewell embrace from me. His mother gives him her blessing, clings to his reins, watches him go while she whispers her prayers, and looks curiously at me, as I stand dry-eyed and watch him ride off at the head of his guard, three hundred of them, to meet with Lord Daubney.

“Are you not afraid for him?” she asks, her eyes moist, her old lips trembling. “Your own husband, going out to war, to battle? You did not kiss him, you did not bless him. Are you not afraid for him riding into danger?”

“Really, I doubt very much that he’ll get too close,” I say cruelly, and I turn and go inside to the second-best apartment.

EAST ANGLIA, AUTUMN 1497

But England is not as it was. The king’s writ runs up to the high altar now, his mother and her friend the archbishop have made sure of that. There is no sanctuary for the boy though he claims it as a king ordained by God to rule. The abbey breaks its own time-honored traditions, and hands over the boy. Unwillingly, he has to come out to make his surrender to a king who rules England and the Church too.

He came out wearing cloth of gold, and answering to the name of Richard IV—a hastily scribbled note which I guess is from my half brother, Thomas Grey, is tucked under my stirrup when I am taking the children out on their ponies. I did not see the hand that tied it to the stirrup leathers and I can be sure that no one will ever say that I saw it and read it. But when the king questioned him, he denied himself. So be it. Mark it well. If he himself denies it, we can deny him.

I scrunch the paper into a tiny ball and tuck it in my pocket to burn later. It is good of Thomas to let me know, and I am glad that the boy saw one friendly face in a room full of enemies, before he denied himself.

The rest of the news I have, as the court has it, as England has it, in long triumphant dispatches from Henry that are written by him personally, to be read aloud, throughout the country. He sends verbose announcements to the kings of Christendom. I imagine Henry’s words bawled out at every village marketplace, at every town cross, on the steps of country churches, at the entrance to staple halls. He writes as if he were creating a story, and I read it almost smiling, as if my husband were setting up to be a Chaucer, to give the people of England a tale of their beginnings, an entertainment and an explanation. He becomes the historian of his own triumph, and I cannot be the only person who thinks that he has imagined a victory that he did not experience in the windswept fields of Devon. This is Henry the romancer, not Henry a true king.

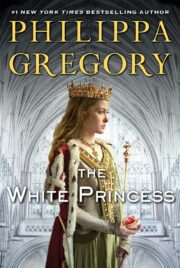

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.