“D’you think he has gone to your aunt?” Henry asks me. Every day he asks me where I think the boy has gone. I have Mary on my knee, and am sitting in a sunny spot in her nursery in a high tower of the beautiful palace. I hold her a little tighter as her father stamps up and down before us, too loud, too big, too furious for a nursery, a man spoiling for a fight and on the edge of losing control. Mary regards him gravely, not at all afraid of him. She watches him as a baby might watch a bearbaiting: a curious spectacle but not one that threatens her.

“Of course I don’t know where he’s gone,” I say. “I can’t imagine. I thought you told me that the Holy Roman Emperor himself had ordered the duchess not to support or succor him?”

“Why would she ever do as she is told?” Henry rounds on me. “Faithless as she is to anything but the House of York? Faithless as she is to anything but ruining my life and destroying my rightful hold on my own kingdom!”

This is too loud for Mary and her lower lip turns down, her face trembles. I turn her towards me and show her a smile. “There,” I say. “Hush. Nothing’s wrong.”

“Nothing’s wrong?” Henry repeats incredulously.

“Nothing for Mary,” I say. “Don’t distress her.”

His angry glance falls on her as if he would shout to warn her that she is in danger, her house on the brink of collapse, thanks to an enemy like a will-o’-the-wisp. “Where is he?” he asks again.

“Surely, you have all the ports watched?”

“Costs me a fortune, but there is not an inch of the coast that is not patrolled.”

“Then if he comes, you will know. Perhaps he has gone back to Ireland.”

“Ireland? What d’you know about Ireland?” he demands, swift as a snake.

“I don’t know!” I protest. “How should I know? It’s just that he was there before. He has friends there.”

“Who? What friends?”

I stand up to face him, holding Mary close. “My lord, I don’t know. If I knew anything, I would tell you. But I know nothing. All I ever hear is what you tell me, yourself. No one else speaks to me of him, and anyway, I would not listen if they did.”

“The Spanish may yet take him,” Henry says, more to himself than to me. “They have promised him their friendship and they will capture him for me. They have promised me that they have ships waiting off the coast for him and he has agreed to meet with them. Perhaps they will—”

There is a sudden loud hammering on the door, Mary cries out, and I clutch her tighter to me and stride across the room, away from the door, towards the bedroom, as if I am running away, suddenly afraid. Henry spins on his heel, his face white. I pause on the threshold of the bedroom door, Henry just a step before me so that when the messenger walks in, dirty from the road, he sees the two of us, pale with fear, as if we are expecting attack. He drops to his knee. “Your Grace.”

“What is it?” Henry demands roughly. “You frightened Her Grace, coming in so loudly.”

“It’s an invasion,” he says.

Henry sways and clutches at the back of the chair. “The boy?”

“No. The Scots. The King of Scots is marching.”

We have to trust Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey, my sister Anne’s husband, to save England for Henry. We, who trust nothing and fear everything, have to trust to him; but it is the rain that serves us best. Both the English and the Scots set sieges and are all but destroyed by the unceasing rain. The English troops, camped on wet ground before stoical castles, fall ill, and melt away in the driving mist to their own homes, to warm fires and dry clothes. Thomas Howard cannot keep them loyal, cannot even keep them in their ranks. They don’t want to fight, they don’t care that Henry is defending his kingdom against England’s oldest enemy. They don’t care about him at all.

Thomas Howard stands before Henry in the privy chamber. I am at one side of Henry’s great chair, his mother at the other, as Henry rages at him, accusing him of dishonesty, treachery, faithlessness.

“I could not make the men stay,” Thomas says miserably. “I could not even make their leaders stay. They had no appetite for the fight and there were scant rewards. You don’t know what it was like.”

“Are you saying I don’t go to war?” Henry bursts out.

Thomas shoots a quick horrified glance at me, his sister-in-law. “No, Your Grace, of course not. I only meant that I cannot describe to you how hard this campaign is. It’s very wet and very cold in this part of your country. The food is scanty and it’s hard to get firewood in some places. Some nights the men had to sleep without anything to eat in the cold rain, and wake without breakfast. It’s hard to supply an army and the men had no passion for the fight. Nobody doubts Your Grace’s courage. That has been shown. But it is hard to make the men stand firm in this country in this weather.”

“Enough of this. Can you take the field again?” Henry is biting his lips, his face dark and furious.

“If you command me, Sire,” Surrey says miserably. He knows, as we all do, that any hint of refusal will see him back in the Tower, named as a traitor, his marriage to Anne not enough to save him. Again he glances quickly at me, and sees at once, from my impassive expression, that I cannot help him. “I should be proud to lead your men. I will do my best. But they have gone home. We will have to muster them all over again.”

“I can’t keep hiring men,” Henry decides abruptly. “They won’t serve, and I have no funds to pay them. I shall have to make peace with Scotland. I hear that James is down to the last coin in his treasury too. I shall make peace. And I shall move what men I have left away from the borders. They must come south to be ready.”

“Ready for what?” his mother asks.

I don’t know why she asks, except to hear her own fears in words.

“Ready for the boy.”

WOODSTOCK PALACE, OXFORDSHIRE, AUTUMN 1497

The court is preparing to go out hawking, the riders mounting, the hawk carts with the rows of hooded hawks rolling out of the mews, the falconers running alongside the carts speaking soothingly to the blind birds, promising them sport and feeding if they will be good birds, be steady and patient now, stand proudly on their perches: don’t bate, don’t flap.

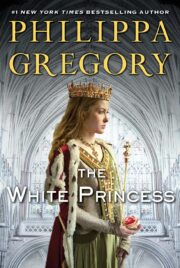

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.