“And Arthur?” I ask her.

She smiles at me. “He is a prince to be proud of,” she says. “He is generous, and fair. When Sir Richard takes him to watch the judges at their work his desire is to be merciful. He rides well and when he goes out he greets people as his friend. He is everything that you would want him to be. And Richard is teaching him all that he knows. He’s a good guardian for your boy. Arthur will make a good king, perhaps even a great king.”

“If the boy does not claim his throne.”

“Perhaps the boy will think that loving a woman and loving his child is enough,” Maggie says. “Perhaps he will understand that a prince does not have to become a king. Perhaps he will think that it is more important to be a man, a loving man. Perhaps when he sees his wife with the child in her arms he will know that this is the greatest kingdom a man can wish for.”

“If I could tell him that!”

“I can’t get a letter to my own brother, just down the river in the Tower of London. How could we ever get a letter to yours?”

THE TOWER OF LONDON, SUMMER 1497

In days, in moments, they are agreed and furious; they go through the west like a summer fire, blazing up, jumping a field or two, raging on faster than a galloping horse. Soon they have the whole of Cornwall up in arms, and then the other western counties join with them, equally angry. They form separate armies led by men from Somerset, Wiltshire, and Cornwall under the command of a Cornish blacksmith, Michael Joseph, An Gof, a man said to be ten feet high who has sworn that he will not be ruined by a king whose father was no king, who is trying new ways, Tudor ways, Welsh ways against good Cornishmen.

But it is not just a rebellion of ignorant men: yeomen turn out for them, fishermen, farmers, miners, and then, worst of all, a nobleman, Lord Audley, offers to lead them.

“I’ll leave you and my mother and the children here,” Henry says tersely to me, his horse waiting at the head of his yeomen of the guard, who are arrayed in battle order outside the White Tower, the gates closed, the cannons rolled up to the walls, everything ready for a war. “You’ll be safe here, you can hold out against a siege for weeks.”

“A siege?” I hold Mary on my hip, as if I were a peasant woman seeing a husband off to battle, her own future desperately uncertain. “Why, how close are they going to get to London? They’re coming all the way from Cornwall! They should have been contained in the West Country! Are you leaving us with enough troops? Is London going to stay loyal?”

“Woodstock, I’m going to Woodstock. I can muster troops there and cut off the rebels as they come up the Great West Way. I have to get my troops back from Scotland, as soon as I can. I sent them all north to face the boy and the Scots, I wasn’t expecting this from the southwest. I’m recalling Lord Daubney and his force, I’ve sent orders for them to turn back south at once. I’ll get them back here, if the messenger finds them in time.”

“Lord Daubney is a Somerset man,” I observe.

“What d’you mean by that?” Henry shouts at me in his desperation, and Mary flinches at his raised voice and wails pitifully. I tighten my grip on her little plump body and rock her, stepping from one foot to the other.

I keep my voice low so as not to disturb her, and not to unsettle Henry’s bodyguard, who are lining up grim-faced. “I mean only that it will be hard for his lordship to attack his fellow countrymen,” I say. “He will have to fire on his neighbors. The whole county of Somerset has joined with the Cornishmen, and he will have known Lord Audley from boyhood. I don’t suggest that he will fail you, I just mean that he is a man from the west and he is bound to sympathize with his people. You should put other men round him. Where are your other lords? His kinsmen and peers that would keep him to your side?”

Henry makes a sound, almost a moan of distress, and puts his hand on his horse’s neck as if he needs the support. “Scotland,” he whispers. “I have sent almost everyone north, the whole army and all my cannon and all my money.”

For a moment I am silent, seeing the danger that we are in. All my children including Arthur are in the Tower as the rebels march on London, the army is too distant to recall; if Henry’s small force cannot stop them on the road we will be besieged. “Be brave,” I say, though I am sick with fear myself. “Be brave, Henry. My father was captured once and driven from his kingdom once and he still was a great king of England and died in the royal bed.”

He looks at me bleakly. “I’ve sent Thomas Howard the Earl of Surrey to Scotland. He was against me at Bosworth and I kept him in the Tower for more than three years. Do you think that will have made a friend of him? I have to gamble that marriage to your sister makes him a safe ally for me. You tell me that Daubney is a Somerset man and will sympathize with his neighbors as they march against me. I didn’t even know that. I don’t know any of these men. None of them knows me or loves me. Your father was never alone like me, in a strange land. He married for love, he was followed by men with a passion. He always had people that he could trust.”

We take up battle stations in the Tower, with cannon rolled out, the fires kept burning and the cannonballs stacked beside the guns. We hear that there is a mighty rebel army, perhaps as many as twenty thousand men, marching on London from Cornwall and gathering strength as it marches. That is an army big enough to take the kingdom. Lord Daubney gets south in time to block the Great West Way and we expect that he will turn them back, but he does not even delay them. Some say that he orders his troops to clear the road, and lets them go by.

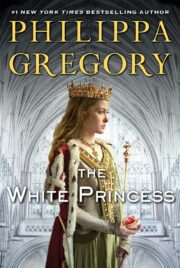

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.