“Who will lead this northern army if the king won’t go?” I ask.

This alone gives her some joy. “Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey,” she says. “We are trusting him with this. Your sister is bearing his child in our keeping, I am certain he won’t betray us. And we have her and his first child as a hostage. The Courtenays will stand by us, and we will marry your sister Catherine to William Courtenay, to make them hold firm. And to have a man who was known to be loyal to the House of York riding against the boy will look good, don’t you think? It must make people stop and think, won’t it? They must see that we kept Thomas Howard in the Tower and he came out safely.”

“Unlike the boy,” I remark.

Her eyes snap towards me and I see terror in her face. “Which boy?” she asks. “Which boy?”

“My cousin, Edward,” I say smoothly. “You still hold him for no reason, without charge, unjustly. He should be released now, so that people cannot say that you take boys of York and hold them in the Tower.”

“We don’t.” She answers by rote as if it is the murmured response to a prayer that she has learned by heart. “He is there for his own safety.”

“I ask for his release,” I say. “The country thinks he should be freed. I, as queen, request it. At this moment, where we should show that we are confident.”

She shakes her head and sits back in her chair, firm in her determination. “Not until it is safe for him to come out.”

I rise to my feet, the proclamation still in my hand that calls for the people to rise against Henry, refuse his taxation, capture him as he flees back to Brittany where he came from. “I can’t comfort you,” I say coldly. “You have encouraged your son to tax people to the point of their ruin, you have allowed him to hide himself away and not go out and show himself and make friends, you have encouraged him to pursue and persecute this boy who now invades us, and you have urged him to recruit an army that he cannot trust, and now to bring in foreign soldiers. Last time he brought in foreign soldiers they brought the sweat, which nearly killed us all. The King of England should be beloved by his people, not an enemy to their peace. He should not be afraid of his own army.”

“But is the boy your brother?” she demands hoarsely. “That’s what I called you here to answer. You know. You must know what your mother did to save him. Is your mother’s favorite boy coming against mine?”

“It doesn’t matter,” I say, suddenly seeing my way clear and away from this haunting question. I have a sudden lift of my spirits as I understand, at last, what I should answer. “It doesn’t matter who Henry is facing. Whether it is my mother’s favorite boy or another mother’s son. What matters is that you have not made your boy the beloved of England. You should have made him beloved and you have not done so. His only safety lies in the love of his people, and you have not secured that for him.”

“How could I?” she demands. “How could such a thing ever be done? These are faithless people, these are a heartless people, they run after will-o’-the-wisps, they don’t value true worth.”

I look at her and I almost pity her, as she sits twisted in her chair, her glorious prie-dieu with its huge Bible and the richly enameled cover behind her, the best rooms in the palace draped with the finest tapestries and a fortune in her strongbox. “You could not make a beloved king, for your boy was not a beloved child,” I say, and it is as if I am condemning her. I feel as hard-hearted, as hard-faced, as the recording angel at the end of days. “You have tried for him, but you have failed him. He was never loved as a child, and he has grown into a man who cannot inspire love nor give love. You have spoiled him utterly.”

“I loved him!” She leaps up suddenly furious, her dark eyes blazing with rage. “Nobody can deny that I loved him! I have given my life for him! I only ever thought of him! I nearly died giving birth to him and I have sacrificed everything—love, safety, a husband of my choice—just for him.”

“He was raised by another woman, Lady Herbert, the wife of his guardian, and he loved her,” I say relentlessly. “You called her your enemy, and you took him from her and put him in the care of his uncle. When you were defeated by my father, Jasper took him away from everything he knew, into exile, and you let them go without you. You sent him away, and he knew that. It was for your ambition; he knows that. He knows no lullabies, he knows no bedtime stories, he knows no little games that a mother plays with her sons. He has no trust, he has no tenderness. You worked for him, yes, and you plotted for him and you strove for him—but I doubt that you ever, in all his baby years, held him on your knees and tickled his toes, and made him giggle.”

She shrinks back from me as if I am cursing her. “I am his mother, not his wet nurse. Why would I caress him? I taught him to be a leader, not a baby.”

“You are his commander,” I say. “His ally. But there is no true love in it—none at all. And now you see the price you pay for that. There is no true love in him, neither to give nor receive—none at all.”

Horrifying stories come from the North, of the Scots army coming in like an army of wolves, destroying everything they find. The defenders of the North of England march bravely against them, but before they can join battle, the Scots have melted away, back to their own high hills. It is not a defeat, it is something far worse than that: it is a disappearance. It is a warning which only tells us that they will come again. So Henry is not reassured, and demands money from Parliament—hundreds of thousands of pounds—and raises more in reluctant loans from all his lords and from the merchants of London to pay for men to be armed and stand ready against this invisible threat. Nobody knows what the Scots are planning, if they will raid constantly, destroying our pride and our confidence in the North of England, coming out of the blizzards at the worst time of year; or if they will wait for spring and launch a full invasion.

“He has a child,” Maggie whispers to me. The court is busy with preparations for Christmas. Maggie and her husband have been at Ludlow Castle with my son Arthur, introducing him to his principality of Wales, but they have come home to Westminster Palace in time to celebrate the Christmas feast. On the way Maggie listens to the gossip in the inns and great houses and abbeys where they stop for hospitality. “They all say that he has a child.”

At once I think how glad my mother would be, how she would have wanted to see her grandchild. “Girl or boy?” I ask eagerly.

“A boy. He’s had a boy. The House of York has a new heir.”

Foolishly, wrongly, I clasp her hands and know that my bright joy is mirrored in her smile. “A boy?”

“A new white rose, a white rosebud. A new son of York.”

“Where is he? In Edinburgh?”

“They say that he’s living with his wife in Falkland, at a royal hunting lodge. They live quietly together with their baby. They say she is very, very beautiful and that he is happy to stay with her, they are so much in love.”

“He won’t invade?”

She shrugs. “It’s not the season, but perhaps he wants to live quietly. Newly married, with a beautiful wife and a baby in her arms? Perhaps he thinks this is the best that he can get.”

“If I could write to him . . . if I could just tell him . . . oh, if I could tell him that this is the best.”

Slowly, she shakes her head. “Nothing goes across the border but the king knows of it,” she says. “If you sent so much as one word to the boy, the king would see it as the greatest betrayal in the world. He would never forgive you, he would doubt you forever, and he would think you have been his hidden enemy all along.”

“If only someone could tell the boy to stay where he is, to find joy and keep it, that the throne won’t bring him the happiness he has now.”

“I can’t tell him,” Maggie says. “I’ve found that truth for myself: a good husband and a place that I can call my home at Ludlow Castle.”

“Have you really?”

Smilingly, she nods. “He’s a good man, and I am glad to be married to him. He’s calm and he’s quiet and he is loyal to the king and faithful to me. I’ve seen enough excitement and disloyalty; I can think of nothing better to do in my life than to raise my own son and to help yours to become a prince, to run Ludlow Castle as you would wish, and to welcome your son’s bride into our home, when she comes.”

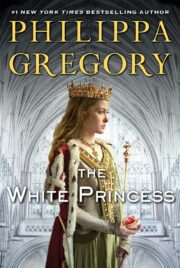

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.