One evening in autumn I am invited into the queen’s rooms—they are still called the queen’s rooms—by My Lady the King’s Mother, who tells me that she needs to talk with me before dinner. I go with Cecily my sister, as Anne is in her confinement, expecting her first child; but when the great double doors are thrown open I see that My Lady’s presence chamber is empty, and I leave Cecily to wait for me there, beside the economical fire of small off-cut timbers, and I go into My Lady’s privy chamber alone.

She is kneeling before a prie-dieu; but when I come in, she glances over her shoulder, whispers “Amen,” and then rises to her feet. We both curtsey, she to me as I am queen, I to her as she is my mother-in-law; we press cool cheeks against each other as if we were exchanging a kiss, but our lips never touch the other’s face.

She gestures towards a chair that is the same height as hers, on the other side of the fireplace, and we sit simultaneously, neither one of us taking precedence. I am beginning to wonder what all this is about.

“I wish to speak to you in confidence,” she begins. “In absolute confidence. What you tell me will not go beyond the walls of this room. You can trust me with anything. I give you my sacred word of honor.”

I wait. I very much doubt that I am going to tell her anything, so she need not assure me that she will not repeat it. Besides, anything that might be of use to her son, she would repeat to him in the next moment. Her sacred word of honor would not even cause a second’s delay. Her sacred word of honor is worth nothing against her devotion to her son.

“I want to speak of long-ago days,” she says. “You were just a little girl and none of it was your fault. No blame is attached to you by me or anyone. Not by my son. Your mother commanded everything, and you were obedient to her then.” She pauses. “You do not have to be obedient to her now.”

I bow my head.

My Lady seems to have trouble in starting her question. She pauses, she taps her fingers on the carved arm of her chair. She closes her eyes as if in brief prayer. “When you were a young woman in sanctuary, your brother the king was in the Tower, but your little brother Richard was still with you in hiding. Your mother had kept him by her side. When they promised her that your brother Edward was to be crowned they demanded that she send Prince Richard into the Tower, to join his brother, to keep him company. Do you remember?”

“I remember,” I say. Despite myself I glance towards the heaped logs in the fireplace as if I could see in the glowing embers the arched roof of the sanctuary, my mother’s white desperate face, the dark blue of her mourning gown, and the little boy that we bought from his parents, took hold of, washed, commanded to say nothing, and dressed up as my little brother, hat pulled low on his head, a muffler across his mouth. We handed him over to the archbishop, who swore he would be safe, though we did not trust him, we did not trust any of them. We sent that little boy into danger, to save Richard. We thought it would buy us a night, perhaps a night and a day. We could not believe our luck when no one challenged him, when the two boys together, my brother Edward and the pauper child, kept up the deception.

“The lords of the privy council came and demanded that you hand your little brother over to them,” My Lady says, her voice a lilting murmur. “But now, I wonder if you did?”

I look at her, meeting her gaze with an honest frank stare. “Of course we did,” I say bluntly. “Everyone knows that we did. The whole privy council witnessed it. Your own husband Thomas, Lord Stanley, was there. Everyone knows that they took my little brother Richard to live with my brother the king, in the Tower, to keep him company before his coronation. You were at court yourself, you must have seen them take him to the Tower. You must remember, everybody knew, that my mother wept as she said good-bye to him, but the archbishop himself swore that Richard would be safe.”

She nods. “Ah, but then . . . then, did your mother lay a little plot to get them out?” My lady draws closer, her hand reaching out like a claw clasping my hands in my lap. “She was a clever woman, and always alert to danger. I wonder if she was ready for them to come for Prince Richard? Remember, I joined my men with hers in an attack on the Tower to rescue them. I tried to save them too. But after that, after it failed, did she save them—or perhaps just save Richard? Her youngest boy? Did she have a plot that she did not tell me about? I was punished for helping her, I was imprisoned in my husband’s house and forbidden from speaking or writing to anyone. Did your mother, loyal and clever woman that she was, did she get Richard out? Did she get your brother Richard out of the Tower?”

“You know that she was plotting all the time,” I say. “She was writing to you, she was writing to your son. You would know more than I do about that time. Did she tell you she had him safe? Have you kept that secret, all this long time?”

She whips back her hand as if I were as hot as the embers in the hearth. “What d’you mean? No! She never told me such a thing!”

“You were plotting with her to free us, weren’t you?” I ask, as sweet as sugared milk. “You were plotting with her to bring in your son to save us? That was why Henry came to England? To free us all? Not to take the throne, but to restore it to my brother and to free us?”

“But she didn’t tell me anything,” Lady Margaret bursts out. “She never told me anything. And though everyone said that the boys were dead, she never held a Requiem Mass for them, and we never found their bodies, we never found their murderers nor any trace or whisper of a plot to kill them. She never named their killers and no one ever confessed.”

“You hoped that people would think it was their uncle Richard,” I observed quietly. “But you didn’t have the courage to accuse him. Not even when he was dead in an unmarked grave. Not even when you publicly listed his crimes. You never accused him of that. Not even Henry, not even you had the gall to say that he murdered his nephews.”

“Were they murdered?” she hisses at me. “If it was not Richard? It doesn’t matter who did it! Were they murdered? Were they both killed? Do you know that?”

I shake my head.

“Where are the boys?” she whispers, her voice barely louder than the flicker of flame in the hearth. “Where are they? Where is Prince Richard now?”

“I think you know better than me. I think you know exactly where he is.” I turn back to her, and I let her see my smile. “Don’t you think it is him, in Scotland? Don’t you think he is free, and leading an army against us? Against your own son—calling him a usurper?”

The anguish in her face is genuine. “They’ve crossed the border,” she whispers. “They’ve mustered a massive force, the King of Scotland rides with the boy at the head of thousands of men, he’s cast cannon, bombards, he’s organized them—no one has seen such an army in the North before. And the boy has sent a proclamation . . .” She breaks off, and from inside her gown she draws it out. I cannot deny my curiosity; I put out my hand and she passes it over. It is a proclamation by the boy, he must have had hundreds made, but at the bottom is his signature, RR—Ricardus Rex, King Richard IV of England.

I cannot take my eyes from the confident swirl of the initial. I put my finger on the dry ink; perhaps this is my brother’s signature. I cannot believe that my fingertip will not sense his touch, that the ink will not grow warm under my hand. He signed this, and now my finger is on it. “Richard,” I say wonderingly, and I can hear the love in my voice. “Richard.”

“He calls upon the people of England to capture Henry as he flees,” Henry’s mother says, her voice quavering. I hardly hear her, I am thinking of my little brother, signing hundreds of proclamations Ricardus Rex: Richard the King. I find I am smiling, thinking of the little boy that my mother loved so much, that we all loved for his sunny good nature. I think of him signing this flourish and smiling his smile, certain that he will win England back for the House of York.

“He has crossed the Scottish border, he is marching on Berwick,” she moans.

At last I realize what she is saying. “They have invaded?”

She nods.

“The king is going to go? He has his troops ready?”

“We’ve sent money,” she says. “A fortune. He is pouring money and arms into the North.”

“He is riding out? Henry will lead his army against the boy?”

She shakes her head. “We won’t put an army in the field. Not yet, not in the North.”

I am bewildered. I look from the bold proclamation in black ink to her old, frightened face. “Why not? He must defend the North. I thought you were ready for this?”

“We can’t!” she bursts out. “We dare not march an army north to face the boy. What if the troops turn on us as soon as we get there? If they change sides, if the men declare for Richard, then we will have done nothing but give him an army and all our weapons. We dare not take a mustered army anywhere near him. England has to be defended by the men of the North, fighting under their own leaders, defending their own lands against the Scots, and we will hire mercenaries to bolster their ranks—men from Lorraine and from Germany.”

I look at her incredulously. “You are hiring foreign soldiers because you can’t trust Englishmen?”

She wrings her hands. “People are so bitter about the taxation and the fines, they speak against the king. People are so untrustworthy, and we can’t be sure . . .”

“You can’t trust an English army not to change sides and fight against the king?”

She hides her face in her hands; she sinks into her chair, almost sinking to her knees as if in prayer. I look at her blankly, unable to conjure an expression of sympathy. I have never in my life heard of such a thing as this: a country invaded and the king afraid to march out to defend his borders, a king who cannot trust the army he has mustered, equipped, and paid. A king who looks like a usurper and calls on foreign troops even as a boy, an unblooded boy, demands his throne.

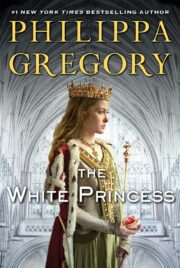

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.