I shake my head.

“They say that everywhere he goes he makes friends!” She is shouting, her voice raised, her face flushed, her anger quite out of control at the mere mention of the boy and his York charm. “They say that the emperor himself, the King of France, the King of Scotland simply fell in love with him. And so we see his alliances: with the emperor, with the King of France, with the King of Scotland, easy alliances that cost him nothing. Nothing! Though we have to pledge peace, or the marriage of our children, or a fortune in gold to earn their friendship! And now we hear that the Irish are mustering for him again. Though they get nothing for it. Not money—for we pay them a fortune to stay loyal—but him they serve for love. They run to his standard because they love him!”

I look past her at my husband, who keeps his head turned away. “You could be beloved,” I say to him.

For the first time he looks up, and meets my eyes. “Not like the boy,” he says bitterly. “Apparently I don’t have the knack of it. No one is beloved like the boy.”

The woman who stopped me on my way to chapel and begged me to tell my husband the king that his subjects could not pay their fines, could not pay their taxes, is one of very many. Again and again people ask me to intercede for them to get a debt forgiven, and again and again I have to tell them that I cannot. Everyone has to pay their fines, everyone has to pay their taxes, and the tax collectors now go armed and ride with a guard. When we go on progress, this summer to the west, and ride over the green hills of Salisbury Plain, we take Henry’s privy purse officers with us, and everywhere we go they make a new valuation of the properties, lands, and businesses, and present a new bill for taxes.

Now I am sorry that I told Henry how my father used to look over the heads of the people reading the loyal address and calculate how much they could pay. My father’s system of loans and fines and borrowings has become Henry’s hated tax system and everywhere we go, we are followed by clerks who count the glass windows in the houses, or the flocks of sheep in the meadows, or the crops in the fields, and present the people who come to see us with a demand for payment.

Instead of being greeted by people cheering in the streets, crowding to wave at the royal children and blow kisses to me, the people are out of sight, bundling their goods into warehouses, smuggling away their account books, denying their prosperity. Our hosts serve the meanest of feasts and hide away their best tapestries and silverware. Nobody dares show the king hospitality and generosity, for either he or his mother will claim it as evidence that they are richer than they pretend, and accuse them of failing to declare their wealth. We go from one great house and abbey to another like grasping tinkers who visit only to steal, and I dread the apprehensive faces that greet us and their looks of relief when we leave.

And everywhere we go, at every stop, there are hooded men, following us like the figure of Death itself, on foundering horses, who speak to my husband in secret and sleep the night and then ride out the next day on the best mounts in the stables. They head west, where the Cornishmen, landowners, miners, sailors, and fishermen are declaring that they will not pay another penny of the Tudor tax, or they ride east, where the coast lies dangerously open to an invasion, or they go north to Scotland, where we hear that the king is building an army and casting guns the like of which have never been seen before, for his beloved cousin: the boy who would be King of England.

“At last I have him.” Henry walks into my room, ignoring my ladies, who leap to their feet and drop into low curtseys, ignoring the musicians, who trail into silence and wait for an order. “I have him. Look at that.”

Obediently I look at the page he shows me. It is a mass of symbols and numbers, saying nothing that I can understand.

“I can’t read this,” I tell him quietly. “This is the language you use: spies’ language.”

He tuts with impatience and draws another sheet of paper from under the first. It is a translation of the code from the Portuguese herald, sealed by the King of France himself to prove that it is true. The so-called Duke of York is the son of a barber in Tournai and I have found his parents and can send them to you . . .

“What do you think of that?” Henry demands of me. “I can prove that the boy is an imposter. I can bring his mother and father to England and they can declare him the son of a barber in Tournai. What do you think?”

I sense Margaret, my cousin, taking a few steps closer to me, as if she would defend me from the rising volume of Henry’s voice. The more uncertain he is, the more he blusters. I rise to my feet and I take his hand in my own.

“I think that it proves your case completely,” I say, just as I would soothe my son Harry, if he were arguing with his brother, near to tears with frustration. “I am sure that this will make your case completely.”

“It does!” he asserts furiously. “It is as I said—he is a poor boy from nowhere.”

“It is just as you said,” I repeat. I look up at his flushed angry face and I feel nothing but pity for him. “This proves that you are completely right.”

A little shudder goes through him. “I shall send for them, then,” he says. “These lowborn parents. I shall bring them to England and everyone can see the lowly parentage of this false boy.”

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, AUTUMN 1496

It is such a ludicrous proposal that when Henry goes on looking for a bereft mother, for a missing boy, for anything—a name if nothing else—that I see it as the measure not of his determination to unravel a mystery, but of his increasing desperation to create an identity for the boy and pin a name on him. When I suggest that really anyone would do, it does not have to be a Tournai barber—he might as well seek anyone who is prepared to say that the boy was born and raised by them, and then went missing—Henry scowls at me and says: “Exactly, exactly. I could have half a dozen parents and still no one would believe that I have found the right ones.”

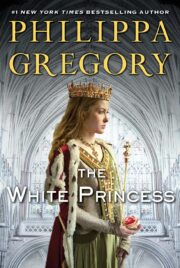

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.