“We are the last,” she says quietly. “I cannot give you false words of comfort. We are the last of the Yorks. You, your sisters, me and my brother, and perhaps England will never see the white rose again.”

“Have you heard anything from Teddy?” I ask.

She shakes her head. “I write, but he doesn’t reply. I am not allowed to visit. He is lost to me.”

We call the new baby Mary, in honor of Our Lady, and she is a dainty pretty little girl, with eyes of the darkest blue and hair of jet black. She feeds well and she grows strong and though I don’t forget her pale, golden-headed sister, I find I am comforted by this new baby in the cradle, this new Tudor for England.

I emerge from confinement to find the country mustering for war. Henry comes to the nursery to see the new baby, but he does no more than glance at her in my arms. He does not even hold her. “There’s no doubt that the King of Scotland will invade, and at the head of his army will be the boy,” Henry says bitterly. “I have to recruit troops in the North and half of them are saying that though they’ll fight against the Scots, they will lay down their arms if they see the white rose. They will defend against the Scots, but they will join a son of York. This is a kingdom of traitors.”

I am holding Mary in my arms, and I feel as if I am offering her as a sop to his temper. There may be a son of York in Scotland, arming and readying his men, but here at our favorite palace of Sheen I have given Henry a Tudor princess, and he will not even look at her.

“Is there nothing we can do to persuade King James not to ally himself with . . . with the boy?”

Henry shoots me a secretive glance. “I have offered him an alliance,” he confesses. “It doesn’t matter if you don’t like it. I doubt that it will stick. We’ll probably never have to send her.”

“Send who?”

He looks furtive. “Margaret. Our daughter Margaret.”

I look at him as if he is mad. “Our daughter is six years old.” I state the obvious. “Do you think to marry her to the King of Scotland, who is—what?—more than twenty?”

“I think to offer her,” he says. “When she is of marriageable age he will only be in his thirties, it’s not a bad match.”

“But my lord—this is to chose all our children’s marriages with your eyes only on the one boy. You have already promised Arthur to Spain in return for them kidnapping him?”

“He won’t go. He’s too cunning.”

“And so, you would give up our little daughter to your enemy to buy the boy?”

“You would rather he was roaming free?” he snaps.

“No, of course not! But . . .”

Already, I have said too much and alerted Henry’s fears.

“I shall propose her as a wife for the King of Scotland, and in return he will give me the boy in chains,” Henry says flatly. “And whether you are thinking of sparing our little girl or of the boy when you say you don’t want such a marriage, it makes no difference. She is a Tudor princess, she must be married where she can serve our interests. She has to do her duty, as I have to do mine—every day. As every one of us has to do.”

I tighten my grip on our new baby. “And this child too? You’ve hardly looked at her. Is every one of our children only of value as a card for you to play? In this one game? In this single unstoppable disproportionate war against a boy?”

He is not even angry; his face is bitter as if his duty is hard for him, harder than anything he would propose for anyone else. “Of course,” he says flatly. “And if Margaret is the price for the death of the boy, then it is a good bargain for me.”

This summer, two new lines are graven on Henry’s face, which run from nose to mouth and mark how his lips are habitually downturned. An habitual scowl grooves his face as one report after another comes to him of the Scottish preparation for war and the weakness of the defenses of northern England. Half of the northern gentry have already crossed over the border of Scotland to be with the boy, and the families they have left behind are not stirring themselves to fight for Henry against their kinsmen.

Every evening after dinner Henry goes to his mother’s rooms and the two of them count, again and again, the names of those that they can trust in the North of England. My Lady has drawn up a list of those that they can be sure of and those that they doubt. I see both lists when I enter the rooms to bid her good night. The scroll of those they trust and that they judge to be able is weighted with an ink pot, a quill beside it, as if they are hoping to write more names, to add loyalists. The scroll of those they mistrust lolls over the table and unrolls itself towards the floor. Name after name is written with a query beside it. Nothing could exhibit more vividly that the king and his mother are afraid of their own countrymen and -women, that the king and his mother are counting their friends and finding the list too short, that the king and his mother are counting their enemies and seeing the numbers grow every day.

“What do you want?” Henry snaps at me.

I raise my eyebrows at his rudeness in front of his mother, but I curtsey to her, saying very low: “I come to bid you good night, Lady Mother.”

“Good night,” she says. She barely looks up, she is as distracted as her son.

“A woman stopped me on the way to chapel today, and she asked me if her debt to the king could be excused, or if she could be given longer to pay,” I say. “It seems that her husband was charged with a minor offense but he was given no choice of punishment. He has to pay a fine, a very heavy fine. She says they will lose their house and their land and be ruined. She says that he would have preferred to serve time in prison than see everything he has worked for broken up. His name is George Whitehouse.”

They both look at me as if I am speaking Greek. Both of them are utterly uncomprehending. “He is a loyal subject,” I say. “He just got into a brawl. It is hard that he should lose his family home for an alehouse brawl, because the fine is greater than he can pay. The fines were never so heavy before.”

“Do you understand nothing?” My Lady demands, and her tone is quietly furious. “Do you not see that we have to get every penny, every groat that we can, from everyone in the kingdom, so that we can raise armies and pay for them? Do you think we would excuse some alehouse drunkard his fine when it will buy us a soldier? Even if it buys us an arrow?”

Henry is poring over his list, not even looking up, but I am certain that he is listening. “But this man is a loyal subject,” I protest. “If he loses his house and his family, if he is ruined because the king’s men sell it over his head to collect an impossible fine, then we lose his love and his loyalty. Then we have lost a soldier. The safety of the throne is built on those that love us—only on those that love us. We rule by the consent of the governed—we have to make sure that those who are loyal to us continue as loyal. That list . . .” I point to the names of those whose loyalty is in doubt. “That list will grow if you fine good men into bankruptcy.”

“It’s all very well for you to say such a thing—you who are loved, who have always been loved!” My Lady the King’s Mother suddenly bursts out. “You who come from a family who prided themselves on being so unendingly, so showily . . .” I am horrified, waiting for what she is going to say “. . . so unceasingly endearing!” she spits as if it were the gravest fault. “Endearing! D’you know what they say about the boy?”

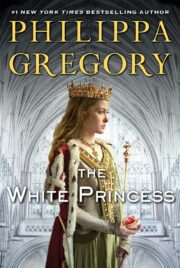

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.