When I say nothing, he nods at my ladies to leave us and they skitter out of the room, their leather shoes slapping on the stone floors, their skirts sweeping the rushes aside.

“The children are next door,” he says. “I ordered them to be housed there, myself. I know you like them to be near you.”

“And where is Edward of Warwick? My cousin?”

“In his usual rooms,” Henry says with a little grimace at his own embarrassment. “Safe and sound, of course. Safe in our keeping.”

“Why did we not stay at Greenwich? Is there some danger that you’re not telling me about?”

“Oh no, no danger.” He rubs his hands before the fire again and speaks so airily that I am now certain something is badly wrong.

“Then why have we come here?”

He glances to make sure that the door is locked. “One of the boy’s greatest adherents, Sir Robert Clifford, is coming back home to England. He betrayed me, but now he’s coming back to me. He can come here and report to me, thinking to win my favor, and I can arrest him without further trouble. He can go from privy chamber to prison—just down a flight of steps!” He smiles as if it is a great advantage to live in a prison for traitors.

“Sir Robert?” I repeat. “I thought he had betrayed you without possibility of return when he left England? I thought he had run away to be with the boy?”

“He was with the boy!” Henry is exultant. “He was with the boy and the foolish boy trusted him with all his treasure and his plans. But he has brought them all to me. And a sack.”

“A sack?”

Henry nods. He is watching me carefully. “A sack of seals. Everyone who is plotting for the boy in England, everyone who ever sent him a letter closed it under their seal. The boy received the letter and cut the seal from it, he kept the seals, by way of a pledge. And now, Sir Robert brings me the sack of seals. I have every seal. A complete collection, Elizabeth, that identifies everyone who is plotting for the boy against me.”

His face is jubilant, like a rat catcher with a hundred rat tails.

“Do you know how many? Can you guess how many?” I can tell by the tone of his voice that he thinks he is setting a trap for me.

“How many?”

“Hundreds.”

“Hundreds? He has hundreds of supporters?”

“But now I know them all. Do you know the names on the list?”

I have to bite my tongue on my impatience. “Of course I don’t know who wrote to the boy. I don’t know how many seals and I don’t know who they are. I don’t even know if it is a true collection,” I say. “What if it is false? What if there are names on it of men who are faithful to you, who perhaps wrote long ago to Duchess Margaret? What if the boy has sent you this sack on purpose, and Sir Robert is working for him, to fill you with doubt? What if the boy is sowing fear among us?”

I see him catch his breath at a possibility that he had not considered. “Clifford has returned to me—the only one who has returned to me!—and brought me information as good as gold,” he says flatly.

“Or false gold, fool’s gold, that people mistake for the real thing,” I say stoutly. I find my courage and I face him. “Are you saying that any of my kinsmen or -women, or ladies, are on the list?” Not Margaret! I am thinking desperately. Not Margaret. God send that she has had the patience not to rebel against Henry in the hopes of freeing her brother. Please God none of my kinswomen have played their husbands false for love of a boy that they secretly think is my brother? Not my grandmother, not my aunts, not my sisters! Please God that my mother always refused to speak with them, just as she never spoke to me. Please God that no one I love is on Henry’s list and that I shall not see my own kinsmen and -women on the scaffold.

“Come,” he says suddenly.

Obediently, I rise to me feet. “Where?”

“To my presence chamber,” he says, as if it is the most ordinary thing in the world that he should come to my room to fetch me.

“I?”

“Yes.”

“What for?” Suddenly my rooms seem very empty, the door to the children’s schoolroom is shut, my ladies sent away. Suddenly I realize that the Tower is very quiet and the prisons for traitors are just a half a dozen steps away, as Henry reminded me just a moment ago. “What for?”

“You can come and see Clifford brought before me. Since you are so astute about whose name might or might not be in his bag of seals, since you are casting doubt on it, you can see it for yourself.”

“It’s a matter for you and your lords,” I say, hanging back.

He puts out his hand, his face quite determined. “You had better come,” he says. “I don’t want people observing your absence and thinking anything of it.”

I put my hand in his, feeling how cold he is as he grips me, and I wonder if it is fear that makes his fingers so icy. “Whatever you wish,” I say steadily, wondering if I can get a message to Margaret, if anyone in the presence chamber will be close enough for me to whisper a request that she bring me something, a shawl or a cape against the cold of the room. “My ladies must come with me.”

“Some of them are there already,” he says. “I particularly wanted them to be there. Some of them have to be there, some of them have questions to answer. You will be surprised at how many people are waiting for us. For you.”

We enter the presence chamber of the Tower hand in hand as if we are in a procession. It is a long room that runs the length of the Tower, dark as it is lit only by narrow windows at either end, crowded this afternoon with people pressing themselves back against the cold walls to leave a space before the banked fire for the table, the great chair, the cloth of estate hung high over the chair. My Lady the King’s Mother stands on one side of the empty throne, her husband Lord Thomas Stanley beside her, his brother Sir William beside him. She has my sisters Cecily and Anne beside her, and Margaret my cousin is there too. Maggie shoots me one frightened look, her eyes dark, and then drops her gaze to the ground.

Sir Robert Clifford, Richard’s friend and loyal companion at the Battle of Bosworth and long before that day, bows as we come in. He looks strained, a leather sack like a pedlar’s pack in one hand, a sheet of paper in the other, as if he were coming to market to deal with a difficult trader. Henry takes the great chair under the cloth of gold, and looks him up and down, as if taking the measure of the man who has turned his coat twice.

“You may tell me what you know,” Henry says quietly.

My Lady steps a little closer to her son’s chair and puts her hand on the carved back, as if she would show them as inseparable, conjoined. In contrast, I find myself shrinking away. Margaret looks at me quickly as if she is afraid that I might faint. The room is stuffy; I can smell the nervous sweat of the waiting lords. I wonder who has good reason to be fearful. I look from Cecily to Anne to Margaret and wonder if they are about to be entrapped. Sir Robert Clifford dabs his damp upper lip.

“I have come straight from the court . . .” he starts.

“It’s not a court,” Henry corrects him.

“From . . .”

“From the feigned lad Warbeck.” Henry speaks for him.

“Warbeck?” Sir Robert hesitates as if to confirm the name, as if he has never heard it before.

Irritated, my husband raises his voice. “Warbeck! Of course! Warbeck! That’s his name, for God’s sake!”

“With this.” Sir Robert holds out the sack.

“The seals of the traitors,” Henry prompts him.

Sir Robert is pale. He nods. “The proof of their treachery.”

“Cut from their treasonous letters to the boy.”

Sir Robert nods nervously.

“You may show me. Show me one at a time.”

Sir Robert steps up to the table, within reach of the king, and I see Jasper Tudor raise himself up on his toes, as if he is ready to spring forwards and defend his nephew against some trick. They are afraid, even now, even in the heart of the Tower, that Henry may be attacked.

It is like a children’s game as Sir Robert plunges his hand in the bag and hands over the first seal. Henry takes it, turns it around in his hand. “Cressener,” he says shortly.

There is a little murmur from one corner of the court, where the absent young man’s kinsmen are standing. They look utterly shocked. A man drops to his knees. “Before God, I knew nothing of it,” he says.

Henry just looks at him, as the clerk behind him makes a note on a sheet of paper. Henry holds out his hand for another seal. “Astwood,” he says.

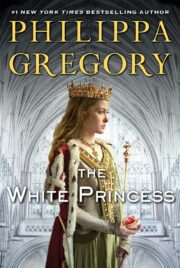

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.