“On the contrary, she assured me that we will marry. It will go ahead. She promised to be my friend.”

My mother hides a smile. “How kind,” is all she says. “Helpful of her.”

So we wait, with some confidence, for our invitation to the coronation, expecting to be told to go to the royal wardrobe to be fitted for our gowns. Cecily, especially, is desperate for her new robes and for the chance for us all to be seen in the world as the five York princesses once more. Only when Henry has reversed the Act of Parliament that named us as bastards and our parents’ marriage as a bigamous fraud can we wear our ermine and crowns once again. Henry’s coronation will be our first chance since Richard’s death to appear to the world in our true colors as princesses of York once again.

I am confident that we will all attend his coronation; yet, still, no word comes. I am certain that he must want his future wife to watch him take the crown on his head and the scepter in his hand. Even if he has no curiosity to see me, how can he not want to demonstrate his victory before us, the previous royal family? Surely he will want me to see him at his moment of greatest glory?

I feel more like a sleeping princess in a fairy story than the woman who is promised in marriage to the new King of England. I may live in the royal palace, and sleep in one of the best rooms, I may be served with courtesy though without the bended knee that people must show to the royal family. But I live here quietly, without a court, without the usual crowd of flatterers, friends, and petitioners, without sight of the king: a princess without a crown, a betrothed without a bridegroom, a bride with no date for her wedding.

God knows that once I was well enough known as Henry’s betrothed. When he was an exiled pretender to the throne, he swore in Rennes Cathedral itself that he was King of England and I was his bride. But, of course, that was when he was mustering his army for his invasion, desperate for support from the House of York and all of our adherents. Now he has won the battle and sent his army away, perhaps he would like to be free of his promise too, as a weapon he needed then, but does not need now.

My mother has seen to it that we all have new gowns; all five of us princesses of York are exquisitely dressed. But we have nowhere to go, and no one ever sees us, and we are called not “Your Grace” as princesses, but “my lady” as if we were the bastard daughters of a bigamous marriage and my mother was not a dowager queen but the widow of a country squire. We are all no better off than Cecily, whose marriage has now been annulled but without a new husband on offer. She is not Lady Scrope but neither is she anything else. We are all girls without a name, without a family, without certainty. And girls like this have no future.

I had assumed that I would be restored as a princess, given my fortune, and married and crowned in one great ceremony at Henry’s side; but the silence tells me that he is not an eager bridegroom.

No message comes from the royal wardrobe bidding us to come and pick out our gowns for the coronation procession. The Master of the Revels does not ask if he may come to the palace to teach us our dance for the coronation dinner. All the seamstresses and tirewomen in London are working day and night on gowns and headdresses: but not for us. Nobody is sent to us from the Lord Chamberlain’s offices with instructions for the procession. We are not invited to stay in the Tower of London the night before the ceremony, as is the tradition. No horses are ordered for us to ride from the Tower to Westminster Abbey, no ruling comes as to the order of precedence on the day. Henry sends no gifts as a bridegroom should to his bride. Nothing at all comes from his mother. Where there should be bustle and business and a host of conflicting instructions from a new king and a new court anxious to look well, there is a silence that grows more and more noticeable as the days go on.

“We’re not going to be invited to the coronation,” I say flatly to my mother when I am alone with her, as she comes to say good night to me in the bedroom that I share with Cecily. “It’s obvious, isn’t it?”

She shakes her head. “I don’t think we are.”

“How can he not have me there at his side?”

Slowly, she goes to the window and looks out at the dark night sky and the silvery moon. “I think they don’t want a host of Yorks beside the throne, so close to the crown,” she says dryly.

“Why not?”

She takes the shutters and latches them, as if to shut out the silvery light that shines on her, giving her an unearthly radiance. “I don’t know why for sure,” she says. “But I suppose, if I was Henry’s mother, I would not want my child, a pretender, a usurper, king only by right of battle, taking his crown alongside a princess, a true-bred princess of the royal family, beloved of the people, and a beauty. Apart from anything else I would not like how it looked.”

“Why? What does he look like?” I demand.

“Ordinary.” My mother condemns him in one damning word. “He’s very, very ordinary.”

Slowly it becomes clear to us all, even to Cecily, who is frantically hopeful almost up to the last day, that the new king will be crowned alone, and that he does not want me, distractingly beautiful, the only true royal, before the altar at his side. He will not even have us, the former royal family, as witnesses when he puts his hand on my lover’s crown, the crown worn by the man I loved, and by my father before him.

No message comes from either Henry or from his mother, Lady Margaret Stanley, to confirm this decision one way or the other, and though my mother and I consider writing to Lady Margaret, neither of us can bear the humiliation of pleading with her for the chance to attend the coronation, nor to beg her to set a date for my wedding.

“Besides, if I were to attend his coronation as a dowager queen I would take precedence over her,” my mother remarks waspishly. “Perhaps that’s why we’re not invited. She has seen nothing but my back at every great event for all of her life. She has never had a view that was not obscured by my headdress and veil. She has followed me into every single room in this palace, and then she followed Anne Neville when she was her lady-in-waiting, too. She walked behind Anne at her coronation, carrying the train. Perhaps Lady Margaret is feeling that it’s her turn to be the first lady now, and she wants someone trailing along behind her.”

“What about me?” Cecily says hopefully. “I’d carry her train. I’d be happy to carry her train.”

“You will not,” my mother says shortly.

Henry Tudor stays in Lambeth Palace until his coronation, and if he should choose to glance up from his breakfast, he would see my window in Westminster Palace, just across the river from him; but presumably he does not choose to look up, he does not wonder about his unknown bride, for still he sends no word. The nights before his coronation, he moves to the Tower of London, as is the tradition. There, he will stay in the royal rooms, and every day he will walk past the door where my brothers were last seen, every day he will walk across the green where my brother had an archery target and practiced shooting his bow. Can a man do such a thing without a chill going down his spine, without glimpsing the pale face of the imprisoned boy who should have been crowned king? Does his mother not see a slight shadow on the stair, or when she kneels in the royal stall in the chapel, does she not hear a faint echo of a boyish treble saying his prayers? How can the two Tudors go up the tightly curled stone stair in the Garden Tower and not listen at the wooden door for the voices of two little boys? And if they ever listen, are they not certain to hear Edward’s quiet prayers?

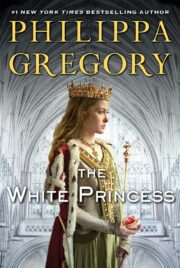

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.