Arthur, always quieter and more sober than his boisterous brother and noisy sister Margaret, sits beside me during the great church service when Thomas Langton, Bishop of Winchester, assists the archbishop to institute Harry as Duke of York. During the banquet, when Henry lifts Harry onto a table so that everyone can see him, Arthur only says quietly: “I hope he doesn’t sing. He’s been longing to sing for everyone.”

I laugh. “I won’t let him sing,” I assure him. “Though he does have a beautiful voice.”

I break off because Margaret, already wild with jealousy at the attention being paid to her brother, slips down from her chair and pulls at the king’s cape. Horrified, her nursemaid runs after her and curtseys low to the king and begs his pardon. But we are in public, celebrating our power. This is not the king whose heart pounds at the sudden noise of a gun salute, who falls into white-faced rage in a moment; this is Henry as he wants people to see him. This Henry does not mind his children out of their chairs, ill-mannered. This is the Henry who has learned what he must do to appear kingly in public. I taught him myself. He roars with laughter as if he is genuinely amused, and he lifts Margaret up so she stands side by side with her brother and waves at the court. He beckons to Elizabeth’s nursemaid and she holds the baby out so that everyone can see the three children side by side.

“The children of England!” my husband shouts exultantly, and everyone cheers. He throws out a hand for Arthur and me to join them. Reluctantly, Arthur stands up and pulls back my chair so that we can both go to the king where he stands, his arms wrapped around his younger children, and all six of us can take the applause as if we were playactors indeed.

Harry turns to his father and whispers. His father bends down to hear and then claps his hands for attention and everyone falls silent. “My son, the Duke of York, is going to sing!” he announces.

Arthur gives me one long inscrutable look and we all stand in silence and listen as Harry, in a sweet light soprano voice, sings “A Very Merry Welcome to Spring” and everyone taps the table or hums the chorus, and when he is done they burst into completely spontaneous applause. Arthur and I smile as if we are quite delighted.

At the end of the two weeks of celebration there is a joust, and Princess Margaret is to award the prizes. I have to order Harry from the royal box, as he cannot bear the disappointment that I will not allow him to ride in the joust on his pony, nor even parade in the arena.

“You can stand here and wave at the crowd, or you can go to the nursery,” I say firmly.

“He has to stay,” my husband overrules me. “He has to be seen by the crowd. And he has to be seen smiling.”

I turn to my sulky little son. “You heard the king,” I say. “You must wave and you must smile. Sometimes we have to do things that we don’t want. Sometimes we have to look happy even when we are sad or angry. We are the royal family of England, we have to be seen in our power and our joy. And we have to look glad.”

Harry always listens to an appeal to his vanity. Sulkily, he bows his copper head only for a moment, and then he steps to the front of the royal box and lifts his hand to wave at the crowd who bellow their approval. The cheers excite him, he beams and waves again, then he bounces like a young lamb. Beyond him, my son Arthur lifts his hand to wave as well, and smiles. Gently, unseen by the crowd, I get a firm grip of the back of Harry’s jacket and hold him still before he shames all of us by jumping over the low wall altogether.

As the jousters come into the arena I catch my breath. I had expected them to be wearing Tudor green, the eternal Tudor green, the compulsory springtime of my husband’s reign. But he and his mother have ordered them into the colors of York to honor the new little Duke of York, and to remind everyone that the rose of York is here, not in Malines. They are all wearing blue and the deep scarlet murrey of my house, the livery I have not seen since Richard, the last king of York, rode out to his death at Bosworth.

Henry catches the look on my face. “It looks well,” he says indifferently.

“It does,” I agree.

The Tudor presence is stated in the roses which stud the arena, white for York overlaid by the red for Lancaster, and sometimes the new rose which they are growing in greater and greater numbers for occasions like this: the Tudor rose, a red marking inside a white flower, as if every York is actually a Lancaster at heart.

Everyone is invited to the tournament and everyone in England comes: loyalist, traitor, and those very many who have not yet made up their minds. London is filled with people, every lord from every county in England has come with his household, every squire has come with his family, everyone has been commanded to come to celebrate the ennobling of Henry. The palace is filled, there is not a spare inch of floor in the great hall, everyone beds down where they can find a space. The inns for two miles in every direction are bursting at the seams, with four to a bed. All the private houses take in guests, the very stables host men sleeping in the hay barns above the horses. And it is this concentration of so many lords and gentry, citizens, and commoners, this gathering of all the people of England, that makes it so easy, so horribly easy for Henry to arrest everyone he suspects of treason or disloyalty, or even a word out of place.

The moment the joust is over and before anyone can go home, Henry sends out his yeomen of the guard, and men—guilty and innocent alike—are snatched from their lodgings, from their houses, some even from their beds. It is a magnificent attack on everyone whose names Henry has compiled from the time that the boy was first mentioned till now, at the moment that they were most unsuspecting, when they had stepped into Henry’s trap. It is brilliant. It is ruthless. It is cruel.

The lawyers are not alert, most of them have come to the joust as guests, the clerks are still taking their holidays. The accused men can find no one to represent them, they cannot even find their friends to post the massive fines that Henry sets for them. Henry snatches them up quickly, dozens at a time, in a city that has been lulled into carelessness by days of merrymaking into forgetting that they are ruled by a king who is never careless, and hardly ever merry.

THE TOWER OF LONDON, JANUARY 1495

“This is cozy,” he says, warming his hands at the fire.

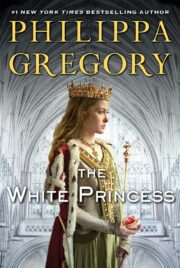

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.