He is free at last to be a young man, to be a happy man. The long years of hiding, of fear, of danger seem to slide away from him and he begins to think that he has come to his own, that he can enjoy his throne, his country, his wife, that these goods are his by right. He has won them, and nobody can take them from him.

The children learn to approach him, confident of their welcome. I start to joke with him, play games of cards and dice with him, win money from him and put my earrings down as a pledge when I up the stakes, making him laugh. His mother does not cease her constant attendance at chapel but she stops praying so fearfully for his safety and starts to thank God for many blessings. Even his uncle Jasper sits back in his great wooden chair, laughs at the Fool and stops raking the hall with his hard gaze, ceases staring into dark corners for a shadowy figure with a naked blade.

And then, just two nights before Christmas, the door to my bedchamber opens and it is as if we had fallen back to the early years of our marriage and all the happiness and easiness is gone in a moment. A frost has fallen; the habitual darkness comes in with him. He enters with a quick cross word to his servant, who was following with glasses and a bottle of wine. “I don’t want that!” he spits, as if it is madness even to suggest it, he has never wanted such a thing, he would never want such a thing; and the man flinches and goes out, closing the door, without another word.

Henry drops into the chair at my fireside and I take a step towards him, feeling the old familiar sense of apprehension. “Is something wrong?” I ask.

“Evidently.”

In his sulky silence, I take the seat opposite him and wait, in case he wants to speak with me. I scan his face. It is as if his joy has shut down, before it had fully flowered. The sparkle has gone from his dark eyes, the color has even drained from his face. He looks exhausted, his skin is almost gray. He sits as if he were a much older man, plagued with pain, his shoulders strained, his head set forwards as if he were pulling against a heavy load, a tired horse, cruelly harnessed. As I watch him he puts his hand over his eyes as if the glow from the fire is too bright against the darkness within, and I am moved with sudden deep pity. “Husband, what is wrong? Tell me, what has happened?”

He looks up at me as if he is surprised to find that I am still there, and I realize that his reverie was so deep that he was far away from my quiet warm chamber, straining to see a room somewhere else. Perhaps he was even trying to see back into the darkness of the past, to the room in the Tower and the two little boys sitting up in their bed in their nightshirts as their door creaked open and a stranger stood in the entrance. As if he is longing to know what happens next, as if he fears to see a rescue, and hopes to see a murder.

“What?” he asks irritably. “What did you say?”

“I can see that you are troubled. Has something happened?”

His face darkens and for a moment I think he will break out and shout at me, but then the energy drains from him as if he were a sick man. “It’s the boy,” he says wearily. “That damned boy. He’s disappeared from the French court.”

“But you sent . . .”

“Of course I sent. I have had half a dozen men watching him the moment he arrived in the French court from Ireland. I have had a dozen men following him since King Charles promised him to me. Do you think I am an idiot?”

I shake my head.

“I should have ordered them to kill him then and there. But I thought it would be better if they brought him back to England for execution. I thought we would hold a trial where I would prove him to be an imposter. I thought I would create a story for him, a shameful story about poor ignorant parents, a drunk father, a dirty occupation somewhere on a river near a tannery, anything to take the shine off him. I thought he would be sentenced to execution and I would have everyone watch him die. So that they would all know, once and for all, that he is dead. So that everyone would stop mustering for him, plotting for him, dreaming of him . . .”

“But he’s gone? Run away?” I can’t help it; whoever he is, I hope that the boy has got away.

“I said so, didn’t I?”

I wait for a few moments as his ill-tempered snarl dies away and then I try again. “Gone where?”

“If I knew that, I would send someone to kill him on the road,” my husband says bitterly. “Drown him in the sea, drop a tree on his head, lame his horse, and cut him down. He could have gone anywhere, couldn’t he? He’s quite the little adventurer. Back to Portugal? They believe he is Richard there, they refer to him as your father’s son, the Duke of York. To Spain? He has written to the king and queen as an equal and they have not contradicted him. To Scotland? If he goes to the King of Scots and together they raise an army and come against me, then I am a dead man in the North of England; I don’t have a single friend in those damned bleak hills. I know the Northerners; they are just waiting for him to lead them before they rise against me.

“Or has he gone back to Ireland to rouse the Irish against me again? Or has he gone to your aunt, your aunt Margaret in Flanders? Will she greet her nephew with joy and set him up against me, d’you think? She sent a whole army for a kitchen boy, what will she do for the real thing? Will she give him a couple of thousand mercenaries and send him to Stoke to finish off the job that her first pretender started?”

“I don’t know,” I say.

He leaps to his feet and his chair crashes back on the floor. “You never know!” he yells in my face, spittle flying from his mouth, beside himself with anger. “You never know! It’s your motto! Never mind ‘humble and penitent,’ your motto is ‘I don’t know! I don’t know! I never know!’ Whatever I ask you, you always never know!”

The door behind me opens a crack, and my cousin Maggie puts her fair head into the room. “Your Grace?”

“Get out!” he yells at her. “You York bitch! All of you York traitors. Get out of my sight before I put you in the Tower along with your brother!”

She flinches back from his rage but she will not leave me to his anger. “Is everything all right, Your Grace?” she asks me, forcing herself to ignore him. I see she is clinging to the door to hold herself up, her knees weak with fear, but she looks past my furious husband to see if I need her help. I look at her white face and know that I must look far worse, ashen with shock.

“Yes, Lady Pole,” I say. “I am quite all right. There is nothing for you to do here. You can leave us. I am quite all right.”

“Don’t bother on my account, I’m going!” Henry corrects me. “I’m damned if I’ll spend the night here. Why would I?” He rushes to the door and jerks it away from Maggie, who staggers for a moment but still holds her ground, visibly trembling. “I’m going to my own rooms,” he says. “The best rooms. There’s no comfort for me here, in this York nest, in this foul traitors’ nest.”

He storms out. I hear the bang in the outer presence chamber as they ground their pikes as he tears open the door, and then the scuffle as his guard hastily fall in behind him to follow him. By tomorrow, the whole court will know that he called Margaret a York bitch and me a York traitor, that he said my rooms were a foul traitors’ nest. And in the morning everyone will know why: the boy who calls himself my brother has disappeared again.

WESTMINSTER PALACE, LONDON, SPRING 1493

She writes to everyone, in an explosion of gladness, telling them that the age of miracles is not over, for here is her nephew who was given up for dead, walking among us like an Arthur awakened from sleep and returned to Camelot.

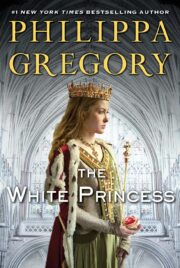

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.