And when the baby is born, after long hours of hard struggle, it grieves me all over again that my mother will never see her. She is such a beautiful baby, with dark, dark blue eyes and beautifully fair hair. But she will never be held by my mother, or rocked by her. She will never hear my mother sing. When they take her away to be washed and swaddled, I feel terribly bereft.

They hold my mother’s funeral without me, while I am still confined, and read her will. They bury her, as she asked, beside the man she adored, her husband King Edward IV. She leaves nothing—my husband Henry paid her so small a pension, and she paid it out so readily, that she died as a poor woman, asking me and my half brother Thomas Grey to settle her debts and to pay for Masses to be said for her soul. She had none of the fortune that my father heaped on her, no treasures of England, not even personal jewels. The people who called her acquisitive, and said that she amassed a fortune with her wiles, should have seen her modest room and her empty wardrobe chests. When they brought her little box of papers and books to my confinement rooms I could not help but smile. Everything she had owned as Queen of England had been sold to finance the rebellions, first against Richard, and then against Henry. The empty jewelry box tells its own story of an unremitting battle to restore the House of York, and I am very sure that the missing boy is indeed wearing a silk shirt that was bought by my mother, and the pearls on the gold brooch in his hat are her gift too.

Lady Margaret, the King’s Mother, comes in state to visit her new grandchild and finds her in my lap, rosy from washing, warm in a towel, unswaddled and beautifully naked.

“She looks well,” she says, her pride in another Tudor baby overcoming her belief that the child should be strapped down on her board to ensure that her legs and arms grow straight.

“She is a beauty,” I say. “A real beauty.”

The baby looks at me with the unswerving questioning gaze of the newborn, as if she is trying to learn the nature of the world, and what it will be like for her. “I think she is the most beautiful baby we have ever had.”

It is true, her hair is silver gilt, a white gold like my mother’s, and her eyes are a dark blue, almost indigo, like a deep sea. “Look at her coloring!”

“That’ll change,” Lady Margaret says.

“Perhaps she’ll be copper-brown like her father. She’ll be exquisite,” I say.

“For a name, I thought we would call her—”

“Elizabeth,” I say, interrupting rudely.

“No, I had thought—”

“She’s going to be Elizabeth,” I say again.

My Lady the King’s Mother hesitates at my determination. “For St. Elizabeth?” she confirms. “It’s an odd choice for a second girl but—”

“For my mother,” I say. “She would have come to me if she could, she would have blessed this baby as she blessed all the others. I had a hard confinement without her here and I expect to miss her for the rest of my life. This baby came into the world just as my mother left it, and so I am naming her for my mother. And I can tell you this—I am absolutely sure that a Tudor Elizabeth is going to be one of the greatest monarchs that England has ever seen.”

She smiles at my certainty. “Princess Elizabeth? A girl as a great monarch?”

“I know it,” I say flatly. “A copper-headed girl is going to be the greatest Tudor we ever make: our Elizabeth.”

GREENWICH PALACE, LONDON, SUMMER 1492

I myself, at the age of about nine, was also delivered up to a certain lord to be killed. It pleased divine clemency that this lord, pitying my innocence, should preserve me alive and unharmed. However, he forced me first to swear upon the sacred body of Our Lord that I would not reveal name, lineage, or family to anyone at all until a certain number of years. Then he sent me abroad.

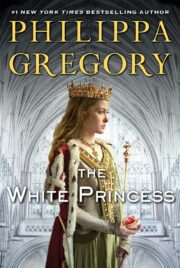

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.