His eyes grow cold at the mere mention of her name. His face slowly freezes, until he looks as if nothing will ever disturb him: a king of stone, a king of ice. “You can write and tell her whatever you wish,” he says. “But I think you’ll find your daughterly tenderness is misplaced.”

“What d’you mean?” I have a sense of dread. “Oh, Henry, don’t be like this! What d’you mean?”

“She knows all about this boy already.”

I can say nothing. His suspicion of my mother is one of the troubles that runs through our marriage like a poisoned stream bleaching a meadow which might otherwise grow green. “I am sure she does not.”

“Are you? For I am quite sure she does. I am sure that what funds I pay her, and what gifts you have given her, are invested in the silk jacket which is on his back, and in the velvet bonnet which is on his head,” he says harshly. “Pinned with a ruby pin, if you please. With three pendant pearls. On his golden curls.”

For a moment I can see my brother’s curls, twisted around my mother’s fingers as he sits with his head in her lap. I can see him so vividly, it is as if I have conjured him, as Henry says the foolish people of Ireland have conjured this prince from death, from the unknown.

“He is a handsome boy?” I whisper.

“Like all your family,” Henry says grimly. “Handsome and charming and with the trick of making people love him. I will have to find him and throw him down before he climbs up, don’t you think? This boy who calls himself Richard Duke of York?”

“I can’t help but wish he was alive,” I say weakly. I look over at my adorable brown-headed son, jumping up to the mounting block to his pony, bright with excitement, and I remember my golden-haired little brother who was as brave and as joyous as Arthur, raised in a court filled with confidence.

“Then you do yourself and your line a disservice. I can’t help but wish him dead.”

I excuse myself from the day’s hawking and instead I take the royal barge and go down the river to Bermondsey Abbey. Someone sees the barge coming in, and runs for my mother to tell her that her daughter the queen is on her way, so she is on the little pier as we land, and comes to meet me, walking through the rowers, who stand at attention, their oars raised in salute, as if she still commanded them, a little nod to one side and the other, a little smile, easy in her authority. She curtseys to me at the gangplank and I kneel for her blessing and bob up.

“I have to talk with you,” I say tersely.

“Of course,” she says. She leads the way into the abbey’s central garden, sheltered by the high warm walls, and gestures to a seat built into a corner, overhung with an old plum tree. Awkwardly I stand, but I nod that she should sit down. The autumn sun is warm; she has a light shawl around her shoulders as she sits before me, her hands clasped lightly in her lap, and listens.

“The king says that you will know all about it already; but there is a boy calling himself by the name of my brother, landed in Ireland,” I say in a rush.

“I don’t know all about it,” she says.

“You know something about it?”

“I know that much.”

“Is he my brother?” I ask her. “Please, Lady Mother, don’t put me off with one of your lies. Please tell me. Is it my brother Richard in Ireland? Alive? Coming for his throne? For my throne?”

For a moment she looks as if she is going to prevaricate, turn the question aside with a clever word, as she always does. But she looks up at my white, strained face, and she puts out her hand to draw me down to sit beside her. “Is your husband afraid again?”

“Yes,” I breathe. “Worse than before. Because he thought it was over after the battle at Stoke. He thought he had won then. Now he thinks he will never win. He is afraid, and he is afraid of being afraid. He thinks he will always be afraid.”

She nods. “You know, words, once spoken, cannot be recalled. If I answer your question you will know things that you should tell your husband and his mother at once. And they will ask you these things explicitly. And once they know that you know them, they will think of you as an enemy. As they think me. Perhaps they would imprison you, as they have imprisoned me. Perhaps they would not allow you to see your children. Perhaps they are so hard-hearted that they would send you far away.”

I sink to my knees before her, and I put my face in her lap, as if I were still her little girl and we were still in sanctuary and certain to fail. “Am I not to ask?” I whisper. “He is my little brother. I love him too. I miss him too. Shall I not even ask if he is alive?”

“Don’t ask,” she advises me.

I look up at her face, still beautiful in this afternoon golden light, and I see that she is smiling. She is a happy woman. She does not look at all like a woman who has lost two beloved sons to an enemy, and knows that she will never see either of them again.

“But you hope to see him?” I whisper.

The smile she turns to me is filled with joy. “I know I will see him,” she says with absolute serene conviction.

“In Westminster?” I whisper.

“Or in heaven.”

Henry comes to my rooms after dinner. He does not sit with his mother this evening, but comes directly to me and listens to the musicians play and watches the women dance, takes a hand at cards and rolls some dice. Only when the evening ends and the people make their bows and their curtseys and withdraw does he pull up his chair before the great fire in my presence chamber, snap his fingers for another chair to be placed beside him, and gesture that I shall sit with him, and that everyone but a servant, standing at the servery, shall leave us.

“I know that you went to see her,” he says without preamble.

The man pours a tankard of mulled ale and puts a small glass of red wine on a table beside me, and then makes himself scarce.

“I took the royal barge,” I say. “It was no secret.”

“And you told her of the boy?”

“I did.”

“And did she know already?”

I hesitate. “I think so. But she could have learned it from gossip. People are starting to talk, even in London, about the boy in Ireland. I heard about it in my own rooms tonight; everyone is talking, again.”

“And does she believe that this is her son, returned from the dead?”

Again I pause. “I think that she may do. But she is never clear with me.”

“She is unclear because she is engaged in treason against us? And does not dare to confess?”

“She is unclear because she has a habit of discretion.”

He laughs abruptly. “A lifetime of discretion. She killed the sainted King Henry in his sleep, she killed Warwick on the battlefield shrouded in a witch’s mist, she killed George in the Tower of London drowned in a barrel of sweet wine, she killed Isabel his wife and Anne, the wife of Richard, with poison. She has never been accused of any of these crimes, they are still secret. She is indeed discreet, as you say. She’s murderous and discreet.”

“None of that is true,” I say steadily, disregarding the things that I think may be true.

“Well, at any rate . . .” He stretches his boots towards the fire. “She did not tell you anything that would help us? Where the boy comes from? What are his plans?”

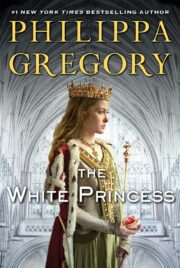

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.