“You’re tired, I shouldn’t have troubled you with this.”

“No. Not tired. Only weary at the thought of another pretender.”

“Yes,” he says, suddenly emphatic. “That’s what he is. You are right to name him so. Another pretender. Another liar, another false boy. I shall have to hunt him down, find out who he is and where he comes from, attack his story, split his lies like kindling, disgrace his sponsors, and ruin him and them together.”

I say the worst thing that I could say. “What d’you mean—that it is I who name him as a pretender? Who could he be if not a pretender?”

He stands at once and looks down on me, as if we were newly married and he still hated me. “Exactly. Who would he be if not a pretender? Sometimes, Elizabeth, you are so stupid that I find you quite brilliant.”

He walks out of the room, pale with resentment, and Maggie glances across at me and she looks afraid.

I come out of my confinement to dazzlingly hot summer weather and find the court anxious despite the birth of a second son. Every day brings a new message from Ireland, and the worst of it is that nobody dares to speak of it. Sweating horses stand in the stable yard, men caked in dust are taken straight in to see the king, his lords sit with him to hear their report, but nobody remarks upon it. It is as if we are at war but nobody will say anything; we are under siege in silence.

To me it is clear that the King of France is taking revenge on us for our long, loyal support of Brittany against him. My uncle died to keep Brittany independent from France; Henry never forgets that he found a safe exile in the little dukedom. He is honor-bound to support his former hosts. There is every reason for us to see France as our enemy. But for some reason, though the privy council is all but a council of war, nobody speaks openly against France. They say nothing, as if they are ashamed. France has put an army into our kingdom of Ireland and yet nobody rages against them. It is as if the lords feel that it is our fault, the failure of Henry to be a convincing king, that is the real problem, and that the French invasion is just another sign of this.

“The French don’t care about me,” Henry says to me tersely. “France is the enemy of the King of England, whoever he may be, whatever the color of his jacket. They want Brittany for themselves, and they want to cause trouble for England. The shame that they bring on me, of two rebellions in four years, means nothing to them. If the House of York were on the throne, then it would be you that they were conspiring against.”

We are standing in the stable yard, and around us is the usual buzz of conversation, the horses led out of their stalls by the grooms, the ladies lifted into the saddles, the gentlemen standing by their stirrups, passing up a glass of wine, holding a glove, talking, courting, enjoying the sunshine. We should be happy, with three children in the nursery and a loyal court around us.

“Of course, France is always our enemy,” I reply comfortingly. “As you say. And we have always resisted an invasion, and we have always won. Perhaps because you were in Brittany for all that long time, you learned to fear them overmuch? For look—you have your spies and your reporters, your posts to bring you news, and your lords who are ready to arm in an instant. We must be the greater power. We have the narrow seas between them and us. Even if they are in Ireland they cannot be a serious danger to us. You can feel safe now, can’t you, my lord?”

“Don’t ask me, ask your mother!” he exclaims, gripped with one of his sudden furies. “You ask your mother if I can feel safe now. And tell me what she says.”

PALACE OF SHEEN, RICHMOND, SEPTEMBER 1491

“I want to talk to you,” he says.

I incline my head towards him and feel him draw me closer.

“We think it is time that your cousin Margaret was married.”

I cannot stop myself glancing over towards her. She is hand in hand with My Lady the King’s Mother, who is speaking earnestly to her. “It looks like more than a thought, it looks like a decision,” I observe.

His smile is boyish, guilty. “It is my mother’s idea,” he admits. “But I think it is a good match for her, and truly—sweetheart—she has to be settled with a man we can trust. Her name, and the presence of her brother, mean that she will always live uneasily under our rule. But we can change her name at least.”

“Who have you picked out for her?” I ask. “For Henry, I warn you, I love her like a sister, I don’t want her sent away to Scotland or”—I am suddenly suspicious—“bundled off to Brittany, or to France to make a treaty.”

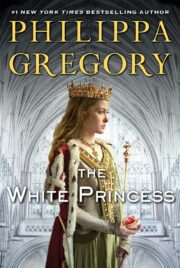

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.