“I’m not disappointed in a girl,” he assures me as he meets me in the nursery and I find him with the precious baby in his arms. “We need another boy, of course, but she is the prettiest, daintiest little girl that was ever born.”

I stand at his shoulder and look into her face. She is like a little rosebud, like a petal, hands like little starfish and fingernails like the tiniest shells ever washed up by a tide.

“Margaret for my mother,” Henry says, kissing her white-capped little head.

My cousin Maggie steps forwards to take the baby from us. “Margaret for you,” I whisper to her.

GREENWICH PALACE, LONDON, JUNE 1491

“We’ll call him Henry,” he declares, as the boy is put into his arms when he visits me, a week after the birth.

“Henry for you?” I ask him, smiling from the bed.

“Henry for the sainted king,” he says sternly, reminding me that just when I think we are most happy and most easy, Henry is still looking over his shoulder, justifying his crown. He looks from me to my cousin Margaret as if we were responsible for the old king’s imprisonment in the Tower and then his death. Margaret and I exchange one guilty look. It was probably our fathers working together with our uncle Richard who held a pillow over the poor innocent king’s sleeping face. At any rate, we are close enough to the murder to feel guilt when Henry calls the old king a saint and names his newborn son for him.

“As you wish,” I say lightly. “But he does look so like you. A copper-head, a proper Tudor.”

He laughs at that. “A redhead, like my uncle Jasper,” he says with pleasure. “Pray God gives him my uncle’s luck.”

He is smiling, but I can see the strain around his eyes, with the look I have come to dread, as if he is a man haunted. This is how he looks when he bursts out in sudden complaints. This is the look that I think he wore for all those years when he was in exile and he could trust no one and feared everybody, and every message that he had from home warned him of my father, and every messenger who brought it could be a murderer.

I nod to Maggie, who is as sensitive as I am to Henry’s uncertain temper, and she takes the baby and gives him to his wet nurse, and then sits beside the two of them, as if she would disappear behind the woman’s warm bulk.

“Is something the matter?” I ask quietly.

He glares at me for a moment, as if I have caused the problem, and then I see him soften, and shake his head. “Odd news,” he says. “Bad news.”

“From Flanders?” I ask quietly. It is always my aunt who causes this deep line between his brows. Year after year she goes on sending spies into England, money to rebels, speaks against Henry and our family, accuses me of disloyalty to our house.

“Not this time,” he says. “Perhaps something worse than the duchess . . . if you can imagine anything worse than her.”

I wait.

“Has your mother said anything to you?” he asks. “This is important, Elizabeth. You must tell me if she has said anything.”

“No, nothing,” I say. My conscience is clear. She did not come into confinement with me this time, she said she was unwell and feared bringing illness into the room with her. At the time I was disappointed, but now I have a clutch of apprehension that she stayed outside to weave treasonous plots. “I have not seen her. She has written nothing to me. She is ill.”

“She’s said nothing to your sisters?” he asks. He tips his head to where Maggie sits beside the wet nurse, petting my son’s little feet as he sleeps. “She’s said nothing? Your cousin of Warwick? Margaret? Nothing about her brother?”

“She asks me if he can be released,” I remark. “And I ask it of you, of course. He is doing nothing wrong—”

“He’s doing nothing wrong in the Tower because he is powerless to do anything as my prisoner,” Henry says abruptly. “If he were free, God knows where he would turn up. Ireland, I suppose.”

“Why Ireland?”

“Because Charles of France has put an invasion force into Ireland.” He speaks in a suppressed angry mutter. “Half a dozen ships, a couple of hundred men wearing the cross of St. George as if they were an English army. He has armed and fitted out an army marching under the flag of St. George! A French army in Ireland! Why d’you think he would do that?”

I shake my head. “I don’t know.” I find I am whispering like him, as if we are conspirators, planning to overthrow a country, as if it is we who have no rights, who should not be here.

“D’you think he is expecting something?”

I shake my head. Truly, I am baffled. “Henry, really, I don’t know. What would the King of France be expecting to come out of Ireland?”

“A new ghost?”

I feel a shiver crawl slowly down my spine like a cold wind, though it is a summer day, and I gather my shawl around my shoulders. “What ghost?”

At that single potent word, I have lowered my voice like him, and the two of us sound as if we are calling up spirits as he leans towards me and says, “There’s a boy.”

“A boy?”

“Another boy. A boy who is trying to pass himself off as your dead brother.”

“Edward?”

“Richard.”

My old pain, at the name of the man I loved, given to the brother that I lost, taps on my heart like a familiar friend. I tighten my shawl again and find that I am hugging myself, as if for comfort.

“A boy pretending to be Richard? Who is he? Another false boy, another imposter?”

“I can’t trace this one,” Henry says, his eyes dark with fear. “I can’t find who’s backing him, I can’t discover where he comes from. They say he speaks several languages, carries himself like a prince. They say he is convincing—well, Simnel was a convincing child, that’s what they’re trained up to be.”

“They?”

“All these boys. All these ghosts.”

I am silent for a moment, thinking of my husband surrounded in his mind by many boys, nameless boys, ghost boys. I close my eyes.

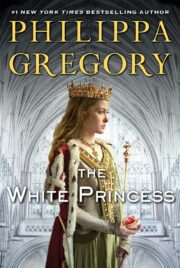

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.